Casting for Supper

The tide was turning, and I was becoming anxious. No matter the respect shown the ocean, she treats us with indifference, the moon’s gravitational pull her only master. But given the riveting scenery of Point Reyes National Seashore, I’d taken my time hiking to the beach’s rocky point, a good hour away, without seeing another soul.

Tidelog for Northern California, with illustrations by revered Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher, always rides shotgun in my old wagon, an indispensable guide chock-full of charts and graphs on tides and currents, sunset and moon phases. A late-morning high tide was predicted, with very little wind.

Every fisherman worth their sea salt has opinions and theories on how and where and when to fish. Most fishermen will tell you, ad nauseam, and usually with a cheap beer in hand, the best times to surf cast for supper are the lower-light hours just after sunrise, or immediately before dusk. And fishing this steeper beach during an incoming tide is also ideal, as rising waters dislodge sand crabs and other small vertebrates from their homes, depositing them into the troughs where the waves break, encouraging fish to feed.

The warm winter sun was now directly overhead, and as light filtered through the occasional cloud the frothy Pacific changed from Persian turquoise to blue-green. Behind me, cliffs the color of cork pulled from an old Chardonnay were sculpted by salt-laced winds into otherworldly shapes, no doubt pleasing Mother Nature’s eye.

A seal bobbed along the waves, diving and mischievously reappearing, like a teasing lover you know you’ll never marry. Black-bellied Plovers, feeding on crustaceans and bivalves at the shoreline, acted as sentinel for other shorebirds, quick to sound their high-pitched whistle when sensing danger. Sanderling sandpipers, their bills as big as their heads, skittered along the water’s edge, lifting offen masse, their murmuration a snapping sailcloth catching the wind.

With every foray into forest, sea or mountain range, the ego is stripped away. The interconnectedness of everything becomes clear, both the markers of life seen and understood, as well as those unseen by naked eye and unimagined by the uninitiated. I was merely half a tiny brushstroke in this grand-scale California plein air.

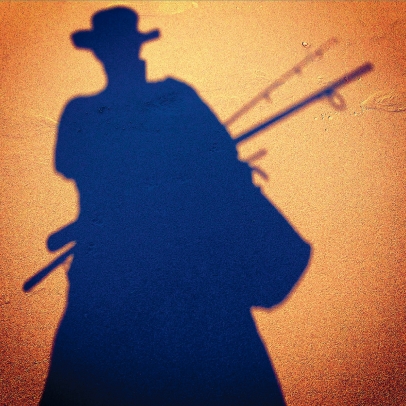

An 11-foot surf rod and reel was split in half and tucked across a treasured L.L. Bean bag, sewn with nautical blue piping and bearing my initials in a blocky monogram, a long-ago gift from my mother during our better years. Thick crackers from a nearby wood-fired oven and hunks of Gouda, aged half a decade and crunchy with calcium lactate crystals, lined the side pocket. Tucked inside were fishing lures in bright colors, chunky four-ounce pyramid sinker weights, a trout priest, a dozen small hooks, needle-nose pliers for removing said hooks, a knife and a semi-frozen block of anchovies. The hooks are teeny tiny, designed to hold tightly onto the bait, making it difficult for craftier fish to pinch. In cards, “fish” refers to an incompetent player whose weaknesses can be easily exploited by the card “shark.” Surely it’s a misnomer, as more often the fish hold the good cards, sending me home sunburned and empty-handed.

At the local sporting shop-cum-hardware store in search of worms and a few pieces of tackle, an old man with crazed eyes and terribly weathered skin reported the rocky outcroppings at the beach’s far, southernmost end covered in mussels. Bivalves and sand crabs are fine enticements on the end of a hook, and can also be chummed into the water’s edge to attract fish. A truly dedicated angler will harvest worms, crab and shrimp at low tide, fishing with this freshly dug bait from the same beach come higher waters. The man warned me to be mindful of the ocean, as sneaker waves are not uncommon, easily dragging off unsuspecting souls and their canine companions. It’s the dogs that survive, he cackled.

Armed with a flat stone for dislodging the mussels and an old carbon steel knife for prying them open, I darted between waves, scouring tide pools and combing through wigs of seaweed concealing the rocks’ bald pates. Not one did I find. Looking up from the protruding peaks of stone, woefully unadorned of mollusk, a winter society ball was in full swing. Dancing diamonds glittering as far as is the sea made it difficult to be annoyed by the old man’s balderdash.

As a set of large waves began to crash against the rocks, I hiked back up the beach, stopping near a congregation of ducks floating in gentler surf. A solitary Snowy Egret blew by, dragging his feet out behind him like a prop plane trailing an advertising banner. Far from the water’s edge, I planted a surf spike deep into the soft beach, which keeps the reel elevated from the gritty, salty sand. I assembled the rod and reel and got busy tying weights and hooks onto the line.

Surfperch are plentiful and caught year round off Northern California’s coast, as opposed to the seasonal harvest of the tastier halibut, the fish of my literal wet dreams. Surfperch are often found in more shallow waters. Calico and Redtail surfperch can be found feeding along the sandy beaches, while Rubberlip, Black and Pile perch dine amongst rocky outcroppings, and near beds of kelp. Their glorious colors and patterns vary, depending upon species and time of year.

The overly generous in-this-day-and-age daily bag and possession limit is 20 fish in a combination of all surfperch species, with not more than 10 fish of any one species (Shiner perch have a separate bag and possession limit of 20 fish). Redtails are the only surfperch that have a minimum size limit—10.5 inches in length. Our seas tapped and fish stocks depleted, we personally now take only what we’re able to eat and share with neighbors, with deep gratitude from gaff to grill.

Now thawed and slimy, a few anchovies were cut into small pieces and threaded onto the pronged hooks. Stripping to a T-shirt and pulling up my pant legs, I edged into the surf, the chilly winter waters immediately anesthetizing my feet. I cast the long rod into the troughs where the waves break, the water’s surge disturbing all kinds of marine life on which surfperch dine. I then cast farther out into more placid holes of deeper water. Calf-deep in surf, arms aching with pleasure, frozen feet dug into shifting sands littered with gangly strands of seaweed, this is my house of worship.

Lost in reverie, I was transported to an East Coast beach at sunset, my father and I hauling onto the sands a dizzying number of bluefish and stripers. As the lighthouse strobe made its rounds, he encouraged me to be methodical in my fishing: If the water’s current is moving to the right, cast to the left and the bait will be pushed along; hold the rod tip high so the line doesn’t drag on the waves; retrieve your lure slowly and steadily, bouncing it along the bottom, reeling only to pick up slack.

As comedian Steven Wright notes, there’s a fine line between fishing and just standing on the shore like an idiot. Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted them: three fat seagulls hovering nearby and intent on a late lunch of rotted anchovy. With frightful precision, they took turns furiously dive-bombing each carefully landed cast, gobbling up my bait. Yelling and screaming and cursing into the afternoon winds, I finally gave up, burying at sea the remaining putrid fish.

Recalling the old British expression “It’s not a fish until it’s on the bank,” I crawled up the beach’s incline to regroup with a nibble and a smoke and a catnap. I awoke as the sun was plunging towards the watery horizon.

Fishing provokes in me a greedy, hopeful high akin to gambling: If I just get out there earlier and stay out a bit longer, try many different spots, stay in the game, get in the zone, I’m bound to get lucky. Like making deals with a junkie, I promised myself I would only cast out five times, maybe six, ensuring arrival to the car in the last spit of daylight.

As the final blush of pink drained from the sky, there was a distinct tug on the end of my line. It wasn’t the unyielding waggle of a hook snagged on a rock or clump of seaweed, nor was it the tug of a large, robust fish, the kind of fish that could keep me and a select few friends fed for a couple of days. But it was the distinct jerk and quiver of a smaller fish, realizing his predicament. Staring into the darkening sky, I reeled carefully and consistently, having lost too many fish on the end of a line reeled in with herky-jerky movements by tired arms. My excitement belying my precise movements, the fish skimmed the top of the water for the last dozen feet before being pulled up and flung onto the sand. Not one but two Calico surfperch flopped around, each the size of a kid’s forearm.

Returning to the draft y, rented cabin, I read the instructions on lighting a fire for heat and longevity, framed and set on the brick mantle, written by Connecticut chef and outdoorsman Charles Van Over. Stacking wood and twigs with yesterday’s morbid headlines, the fire caught quickly, warming my still-frozen toes and drying my pants, which hung from the arms of a corduroy upholstered couch, its cushions low to the ground from years of fireside contemplations.

A dented grill grate was scrubbed and oiled and strung up from the once-brass mermaid andirons, their breasts and tails now a fire-ravaged ebony. A sharpened knife slid easily through the fishes’ bellies, gutting them and leaving behind frilly pink pockets perfect for stuffing with Persian Star garlic, preserved Meyer lemon and Italian parsley. Fingerling potatoes, purchased from Gospel Flat Farm’s open 24/7 honor stand in the neighboring town of Bolinas, were tucked near the embers. Roasted until their flesh was creamy, the earthy tubers were smothered in sweet butter and gobs of thick sour cream from Straus Family Creamery, just up the road. Stalky broccolini was charred and flecked with green oil, Calabrian hot peppers, garlic and the flaky salt eccentrically carried with us everywhere. I managed through the better part of a bottle of Scavino’s Cannubi Barolo, still too young at 12 years of age, while plotting how to best land a perch for the next night’s supper.

“When all the routines and details and the human bores get on our nerves, we just yearn to go away from here to somewhere else. To go fishing is a sound, a valid, and an accepted reason for an escape. It requires no explanation.”

—HERBERT HOOVER (1874–1964)

American engineer, businessman and 31st President of the United States