Understanding Olive Oil

DECIPHERING THE LANGUAGE OF A BELOVED MEDITERRANEAN IMMIGRANT

A few years ago, I went to a three-day symposium on olive oil quality hosted by the Apollo Olive Oil Company in Oregon House, California, a small village in the Sierra foothills not far from Grass Valley. The symposium was led by the late Marco Mugelli, PhD. Mugelli was a founder of the National Association of Olive Oil Tasters based in San Casciano, Italy. He was also chief of the Florence Tasting Panel for the legal evaluation of extra virgin olive oil, an investigator for the improvement of extra virgin olive oil for the Tuscan Chamber of Commerce, and member of the Italian Association of Olive Oil Tasters. Little did I know what I was in for.

By the time the symposium ended, everything I thought I knew about olive oil had been demolished and discarded. Mugelli had filled my mind with so much new and exciting information about this precious substance that I’m still processing and learning from it.

At our very first session, Mugelli started off by asking, “What is olive oil?” He looked around at the eight or so of us. “Anyone?”

A few of us made lame attempts to answer: “One of nature’s most healthful foods?”

“The most popular culinary oil in the world?” “A uniquely flavored oil?”

“Well, all of that may be true, but that’s not what I asked,” he said. “I asked, ‘What IS olive oil?’” And he went on to explain what he meant and to answer his own question.

THE OLIVE’S NATIVE LAND

“The olive tree is native to the Mediterranean region, where winters are mild and wet and summers are hot and dry,” he began. Accordingly, in places like Italy, Spain and Greece, food crops and pastures are grown in the fertile valleys where groundwater is more plentiful. Olives, and also grapevines, are planted up on slopes, because both can withstand the summer droughts of that climate, he explained.

Grapes plunge their roots deeply into the soil, even through cracks in the bedrock, to remain in touch with the little ground moisture that’s down there. This scarcity of moisture keeps the grape berries small, and small grapes make better-tasting wine, he said. That’s because the flavor and color components of grapes are almost all in the skins, and small berries have a much greater skin-to-juice ratio.

SPINNING SUNLIGHT INTO GOLD

Similarly, olives have evolved to endure long summer droughts on dry hillsides and mountaintops. Olive trees photosynthesize sunlight and carbon dioxide and turn them into sugar, as do other plants with chlorophyll in their leaves. The sugar dissolves in the trees’ sap, but the dry climate is not very conducive to storing the sugar—which the plant will use as the energy source to grow new tissues when the rains return—as wet sap. So, the olive tree turns the sugar into fat—olive oil—and stores it in the flesh of olive fruits.

When you think of it, a lot of plants do this. Nut trees, for instance, store oils in their nutmeats, and the avocado, like the olive, changes its sugar to fat and stores it in the fleshy part of its fruit. Forbs like safflower, sunflower and corn all store their sugars as fats. So olives aren’t unique in that regard.

Interestingly, animals store excess energy from their food as fat, too, as the poundage and body shape of habitual overeaters attests. More recently I corresponded with Anne Britt, PhD, a biologist at the University of California at Davis, about this sugar-to- fat phenomenon. Turns out that this conversion happens when the body strips most of the oxygen atoms from sugar molecules, resulting in fatty acids. The fats are then stored in the cells of animals (and certain plants).

“Sugars are not a great storage form for energy,” Britt said. “They take up a lot of water and weigh a lot per calorie.” This is obvious when you look at the formula for a simple sugar like sucrose: C12H22O11. That’s 11 molecules of water hooked onto 12 atoms of carbon. Take away those oxygen atoms and you are left with a vegetable fat like olive oil or an animal fat like butter or tallow. These fats are a more efficient way to store energy. A gram of fat has twice the energy potential as a gram of sugar.

Plants generally like to store sugars as starches, which are simple sugar polymers in near-crystalline form. Starches are intermediate between sugars and fats in compactness and ease of conversion. Place a piece of wheat bread in your mouth and hold it there for a few minutes. The enzymes in your saliva will convert the starch in the wheat back into sugar and the bread will taste sweet.

“Energy is released from sugars and fats by oxidation,” Britt said; that is, by reintroducing oxygen back into the molecule. Think about burning a piece of paper. Burning oxidizes the paper and releases energy in the form of heat. “Sugar is already somewhat oxidized in comparison to fats, so oils and fats carry more potential energy per gram. For animals, that means you don’t have so much weight to haul around.” And for plants like an olive tree, it means you don’t need as much scarce water.

IT TAKES MORE THAN A GOOD UPBRINGING

Not all olive oil is equal. Many factors can lead to oil that has off aromas and flavors, or that simply has no taste at all. Major problems include allowing olives to sit too long after being picked, where they are exposed to heat and pressure (especially if stored in large bins) and start to break down. If this happens, the olives, and resulting oil, acquires an unpleasant flavor referred to as “fusty,” which is the odor of dirty socks. If mold starts to grow on the olives, they can become “musty.” If they start to ferment, they can become “winey,” exhibiting flavors of vinegar.

Long exposure to air, either before crushing or thereafter, oxidizes the free fatty acids in the oil, increasing the oil’s acidity. The more oxidation, the more rancid the oil. International organizations that grade olive oil have set a limit of 0.8% of oxidized fatty acids—any higher and the oils cannot be certified “extra virgin.”

High-quality oils currently being produced in California using modern methods tend to have oxidation levels well below that limit. Oil from McEvoy Ranch, which sits on the Marin-Sonoma county line, tends to have levels around 0.2%, for instance.

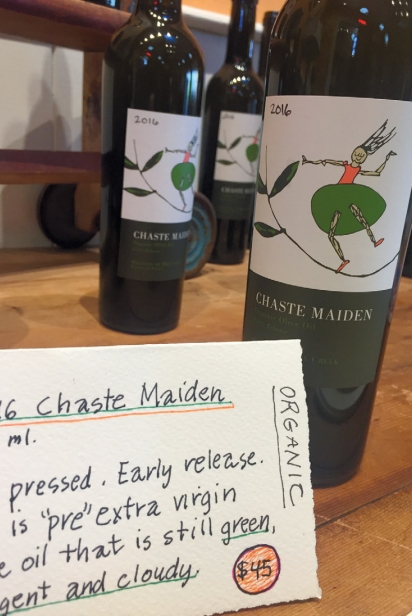

So what are “modern methods” of making oil? First, picking the olives in late fall or early winter when they are just changing color from green to peach, and before they turn black, maximizes the polyphenols in the finished oil. These polyphenols are health-promoting compounds that characterize great oil: fruitiness (the oil smells and tastes like fresh olive fruit), bitterness (from compounds in the underripe fruits) and pungency (that artichoke-y throat-grabbing quality caused by the high levels of polyphenols). Yes, this means that the best, most healthful oils are also the most robust in flavor. Mild taste in an oil is not a quality point.

Olives are also brought to the mill immediately after being picked (90 minutes after picking in the case of McEvoy’s fruit) and dumped into a hammermill. This device has a series of hammers that look like battleaxes with flat hammers instead of slicing edges on them. The hammers beat the olives—pits and all (in fact, it’s the pits that contain most of the polyphenols)—to a paste. The hammering also disrupts the tiny vacuoles in the fruit’s cells that contain odorless, tasteless olive oil. When these vacuoles are ruptured, the oil is spread through the pulp, acquiring flavor.

The paste is then augured into the malaxing chambers—tubes surrounded by water jackets. These tubes hold the paste and revolve for about 45–90 minutes, which causes the oil droplets in the paste to glom together for easier extraction. Warm water at about 80°F. is pumped through the water jackets to warm the paste, which also helps the oil to come together.

The paste is then pumped into a centrifuge. Most facilities that produce high-quality oil use what are called two-stage centrifuges. The olive oil is spun out of one spigot and everything else—the watery olive juice and the olive solids—is ejected from another outlet. The oil is then put into holding tanks, and many oil producers sparge these tanks with nitrogen to keep air off the freshly made juice.

Which brings us back to Professor Mugelli’s deep understanding of olive oil, including the science behind why exposing it to air during processing leads to oxidation and subsequent rancidity. That understanding is what drove his invention of vacuum olive oil extraction equipment that allows all of that malaxing and centrifuging to be done without exposure to the ill effects of air. And why I found myself at a three-day symposium he was leading on the subject.

HOW TO BUY GOOD QUALITY OLIVE OIL

It is first necessary to clear up some common olive oil misconceptions. The term “extra virgin” is basically meaningless. Anyone can use it on any oil—even adulterated, rancid oil. That’s unless the oil is certified by the International Olive Oil Council or the California Olive Oil Council as “extra virgin.” You can trust those certifications if you see them on the label.

You may also see the expression “first cold press” on a label. Once upon a time, olive oil producers made their oil by pulping the olives and slathering the resulting paste on mats, then pressing the mats between large, heavy stones. After they squeezed out as much oil as possible, they then treated the remaining olive paste with hot water to extract the last few drops. Nobody makes oil this way anymore, except maybe for mom-and-pop operations in places like Tunisia that produce inferior oil in any event.

HOW TO STORE OIL AT HOME

When you invest in good-quality olive oil, it is best to store it as you would wine: in a cool place at about 58–60°F, in complete darkness. Never in a hot kitchen cabinet or in the refrigerator. If properly stored, it should retain its freshness for a year.

SOURCES OF HIGH QUALITY OLIVE OIL IN MARIN, NAPA AND SONOMA COUNTIES

DaVero Farms & Winery ● Healdsburg ● Davero.com

Della Terra Oils ● Corte Madera ● DellaTerraOils.com

Dickson Napa Ranch ● Napa ● DicksonNapaRanch.com

Dry Creek Olive Company ● Healdsburg ● DCOC.com

Olive Leaf Hills ● Sebastopol ● OliveLeafHills.com

Grove 45 ● St. Helena ● Grove45.com

Jaeger Olive Oil Co. ● Napa ● JaegerEVO@gmail.com

Katz and Co. ● Napa ● KatzAndCo.com

Lunigiana Estate Extra Virgin Olive Oil ● Glen Ellen ● TheOlivePress.com

McEvoy Ranch ● Petaluma ● McEvoyRanch.com

Nicasio Valley Olive Company ● Nicasio ● Charles@Nicasio.org

O Olive Oil Co. ● Petaluma ● OOliveOil.com

Oliveto del Vecchio ● Potter Valley ● OlivetoDelVecchio.com

Starcross Monastic Community ● Annapolis ● Starcross.org

Terra Trees ● Calistoga ● TerraTrees.com

The Olive Press ● Sonoma ● TheOlivePress.com