Hanson of Sonoma, Where Stomping Grapes into Organic Vodka is a Family Affair

The organic revolution has few frontiers left to conquer, and thanks to a small family operation in the heart of Sonoma County, vodka is no longer one of them.

A few years ago, as a student at the University of Oregon, Chris Hanson spotted an exciting trend during his study abroad in London: an artisanal brewing renaissance that was catching fire about the same time in the U.S. Something in his gut told him craft distilling was about to explode, and he wanted to be a part of it.

Chris approached his parents with the idea, but they told him he needed proof of concept before they’d think about supporting the venture. And so he partnered with his elder brother, Brandon, and the two threw themselves into the field and learned everything they could. Soon enough, they recognized a unique, vodka-shaped hole along the artisanal brewing spectrum and decided to try and fill it.

They went to conventions and expos; talked to bartenders, mixologists, distributors and anyone else who would listen; and found enthusiastic interest. Now, if they could only make what they talked about making, they’d be golden. But that was the hard part.

Vodka is traditionally made with potatoes, corn, wheat and other grains. Rarely it is made with fruit. But when the Hansons, who grew up in Marin County, were devising their recipe, they looked to the vineyards that fill this region. Who is making vodka out of grapes? Nobody. Well, almost nobody. At least no one was doing it up to their standards.

The brothers rented space and began trying out their recipes, honing in on a humble 155 different variations for their classic vodka. They took them to Tony Abou-Ganim, a widely respected mixologist and vodka authority who, they say, was quite difficult to reach until they got their stuff in his hands. He tasted it, loved where it was going, and put together a blind-tasting panel of industry professionals to help the Hansons do a bit more honing.

From the 155 variations, the tasting panel came back with the same top three that the brothers and their other family members also liked best. Shortly thereafter, they shipped a few label-less bottles of “Batch 123” to the Sip Awards, an international competition judged by consumers, designed to cut out the industry bias skewed by outrageous marketing budgets and celebrity endorsements. It’s a good competition for a bottle with no label.

The Hansons thought they might win a bronze or, if they were extra lucky, a silver. When Batch 123 won Best in Show, they didn’t know what to think. Was it a fluke ? Were they onto something? Could it really be this good right off the bat?

And so, they tried again. This time they sent more blank bottles to the Vodka Masters competition in London, a narrower, high-stakes competition focused entirely on vodka. They scored two golds and two silvers—all before they even had their own distillery.

With all of the awards buzz, distributors started calling. Just as they were about to sign with Southern Wine and Spirits—the biggest distributor in the U.S.—they were advised to go with another company that had more experience with small brands. As it turns out, when it comes to getting organic, artisanal vodka on the shelf, a distributing behemoth might not have the right chops.

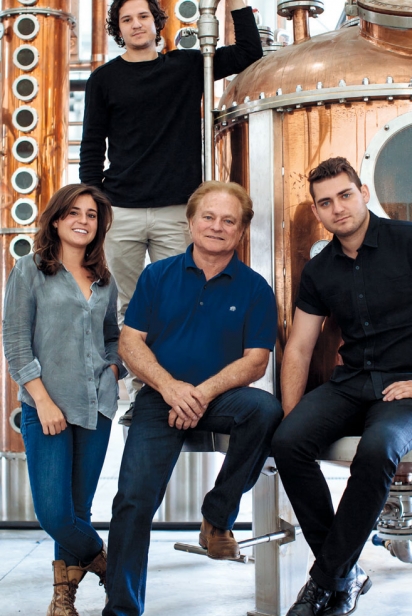

By all appearances, things were about to get serious. Scott Hanson, the father of the clan, was ready to throw his lot in with his sons. Soon enough, the two other Hanson siblings came on board to join the action. Darren, a music student who tended bar on the side, brought his bar skills into the mix. Alanna, a recent USC film studies graduate, brought a finely tuned sensibility for good media. In no time at all, all of the Hanson children were on board. To say Hanson of Sonoma is a family operation feels almost like an understatement; Hanson of Sonoma is the Hanson family.

So how did these rookie distillers win the hearts of the spirits world in such short time? The recipes are proprietary, but so much of it comes down to the ingredients. Everything the family uses is certified organic. Each cucumber, mandarin and boysenberry. When they couldn’t find organic ginger, coffee or cacao locally, they looked to Hawaii.

Standing before the rows of maceration tanks, packed with cucumbers peeled and sliced just so, and thousands of mandarin orange peels, it’s hard to believe it’s all cut by hand. But that’s the Hanson way.

Each bottle has six labels, including a cigar band wrapped around an elongated “tax stamp,” and four of those are applied by hand. It’s one of those things that family friends get excited about doing—manning a labeling shift—but at the end of the day it’s drudgery. “We made a lot of choices that were great for the look and feel of things, but those labels are a nightmare,” says Scott.

But that’s what it takes to make a vodka product that doesn’t look like just another vodka. The Hansons are wine country people, and they wanted to produce a vodka that looked like it was from wine country. Each bottle is individually numbered with a batch number and a bottle number, which means you’ll never get the same number twice.

The Hansons’ project is rife with new ideas and a trailblazing kind of innovation, but the thrust of it all is more or less a throwback to the days when things were done simply, naturally and with integrity.

“There’s a lot of satisfaction to making something with your hands, to having a finished product at the end of the day that you’re proud of and can share with your family and neighbors. To me it says a lot about what we’ve lost,” says Scott.

Being so hands-on is hardly the most efficient way to go, but the Hansons are nothing if not neck-deep in their process. This past harvest season, instead of buying grapes from a few different growers as they typically do, they decided to get closer to the source.

“We needed to get the family involved, so we all woke up for sunrise,” says Scott.

At 6am, the Hansons showed up to the vineyards and got to work picking. Alanna caught some of the action from a drone camera, including one of her brothers napping under the vines. There are different ways to get your hands dirty.

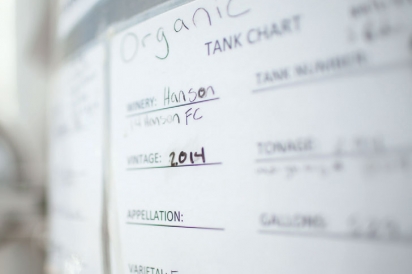

Using all organic ingredients brings with it all the headache that working with any certification does. The family keeps a box of papers to certify each shipment of produce, and the process is heavily audited. But the Hansons don’t traffic lightly in certifications; the vodka is also gluten-free and the first spirit in the U.S. to be certified GMO-free.

But never mind the labels, how does it taste? Right now, the family makes six flavors of vodka, one classic and five with organic infusions. The mandarin rendition uses only peels to impart the flavor because the fruit itself is too acidic and sweet. All hand peeled. In the end, it’s soft and complex. The cucumber vodka is light, sharp and refreshing. The ginger holds a rounded spiciness to it and the espresso vodka is a different animal entirely: deep, robust, complicated.

The remarkable thing is how the subtlety holds up to a 90-proof spirit. These are not in-your-face vodkas. They are a craftsman’s product, and that doesn’t even stop with the grapes. Vodka is hall water, which is why the Hansons have developed the capability to filter their water seven different ways—from activated charcoal to reverse osmosis to UV to ozone. When it comes to vodka, water is hardly a second thought.

Actually, nothing here is a second thought. It’s a project shot through with passion, a project that cuts no corners even when it means making less money and working more slowly.

The idea to distill vodka from grapes was all Chris and Brandon, but Scott plays an encouraging role. He is an enterprising, entrepreneurial man who believes in the purpose of good art. The back wall of the current production facility is lined with movie posters peppered with names like Shia LaBeouf, Matthew Broderick and Gary Oldman. These are souvenirs of Scott’s days as a movie producer, days that are not all that long gone. For a part of his life, he made a practice in believing others’ dreams, in making them real. In a certain light, Hanson of Sonoma doesn’t seem like such a wild transition, especially considering his most recent movie—Lawless—about bootlegging days in Franklin County, West Virginia.

“My dad was an artist, and always entrepreneurial in his own way, and so was my mom. We grew up in such a way where we kind of pursued different ideas and were allowed to and supported,” says Chris.

The dreams are getting bigger, with the family slated to open their own distillery in Carneros this fall. The glass-walled facility, on the same property as the Carneros Brewing Company and Ceja Vineyards’ tasting room, will be open to the public and will showcase the Hanson’s 50-plated copper still that looks like it was ripped straight from the pages of Jules Verne. The recipes might stay secret, but the magic is here for the taking.