Lee Hudson: Agriculturalist, Winemaker and Renaissance Man

It’s 8am and Lee Hudson strides onto the porch of his office surrounded by his dogs–a pack of giant Lurchers, a lanky “Gypsy” breed from Europe. They have been running all over his 2,000 acres and they collapse in a heap as Hudson stops to talk to a guy leaning out of a pickup truck.

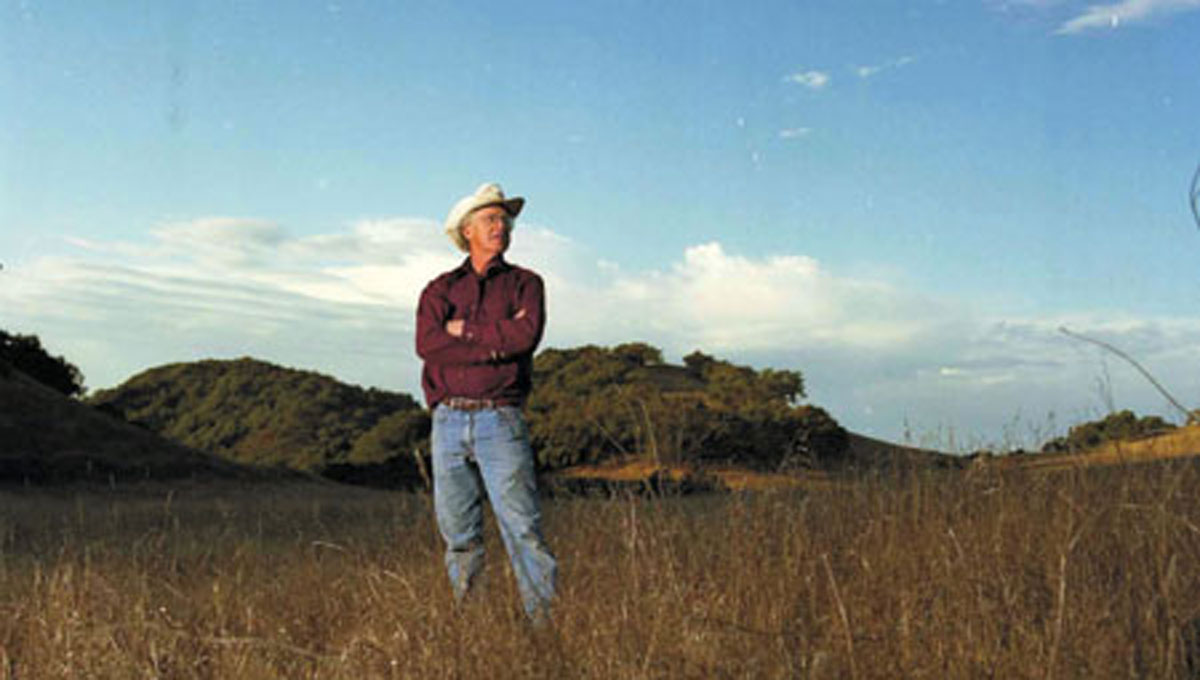

Lee is wearing the grape grower “uniform” often seen around Napa Valley: jeans, white button-down shirt and a cowboy hat–in this case straw (cowboy boots optional). He is fit and compact with sparkling eyes, curly but managed grey hair and Harry Potter-esque glasses. Named Grower of the Year in 2008 by his peers in the Napa Valley Grapegrowers Association, Hudson not only sells his grapes to a “who’s who” of vintners and winemakers, but also produces his own highly coveted Hudson Vineyard wines.

Being a farmer came naturally to Hudson. At 17, he planted his first garden and at 18 worked on an herb farm. Even as a child in Texas he helped his dad on his cattle ranch.

“I remember, as a young child, wine being put in my water. My mother was a very glamorous socialite and she was known for her dinner parties. Part of my childhood was spent in France, and together with her entertaining and my exposure to another culture it gave me an early appreciation for food and wine. My parents told me ‘We don’t care what you do, Lee, but just do it well.’”

Hudson studied horticulture at the University of Arizona, but it was on a visit to the Napa Valley that he experienced an epiphany–he wanted to grow grapes. After graduation and armed with a list of 10 people to contact, he set off for France to work in the vineyards. One by one, they all slammed the door in his face. His last visit was to Domaine Dujac.

“It was fortuitous: The owner took me on because his wife had just delivered a son and he needed to get to Paris to see them.” Hudson worked by day in the vineyard or at the winery and by night he tasted wines with the other vineyard workers.

“Burgundy changed my life–it was the French soil, light and those great Pinots. I learned that great grapes could come from a special site and they could produce truly world-class wines.” After a year, Lee returned to California to attend UC Davis’ esteemed Viticulture and Enology program.

After graduation, Hudson spent some time making wine in Oregon, but California was not forgotten. Finally, in the 1980s, Hudson’s adventure as a grape grower began in earnest with his quest for a vineyard. A certified pilot, he flew all over California looking for just the right vineyard property. The property he found was north of Highway 121–100 acres of unimproved land that was going to be subdivided into 49-acre parcels. The property just seemed right to Hudson. It had been part of a historic ranch established in the 1840s and had contained a vineyard from 1845 until 1966, when it was finally abandoned. At the height of production the ranch was the largest independent grape grower in Napa County.

“I suspected it was great land and the fact I was always interested in the ‘ag’ side, not the wine side, of the business made it the perfect choice,” recalled Hudson. He bought the property even though it had no wells, no electricity and no grapes.

Just 29 years old, he brought all of his Texas spirit, energy and passion to his work with the soil. He set out to talk to growers, visit their vineyards and then started planting. The property offered the perfect environment to create grapes: a combination of exactly the right soil, climate and geography. Hudson’s attention to details and his willingness to learn grape growing and vineyard farming from the ground up, coupled with his creative practices, quickly earned him a reputation in vintner circles of growing grapes that produced some truly outstanding wines. His first clients were his UC Davis friends and classmates such as John Kongsgaard and John Williams.

As his reputation and client base grew, Hudson purchased an adjacent property and named it the Henry Road Ranch. On this second property, a small mountain juts out of the vineyard– the tail end of the Mayacamas as the range disappears into San Pablo Bay (situated at the northern end of San Francisco Bay). The soil here is sandy and full of sandstone riddled with shell fossils. The two properties provide different soils, different climates and different drainage. Together, they produce the three white varietals (Chardonnay, Viognier and Roussanne) and seven red varietals (Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir, Grenache, Syrah, Petit Sirah and Barbera) that Hudson grows.

Today, on the cusp of his 30-year anniversary, Hudson farms over 160 acres of vineyards and sells his fruit to over 30 wineries including Darioush, Blackbird Vineyards, Patz and Hall, Ramey Wine Cellars, Orin Swift Cellars and Kongsgaard, among many others. Hudson is continually sought out by producers and is known for providing exceptional fruit. His client turnover is almost nonexistent. One reason is that, while most growers focus only on the agricultural side of the business, Hudson has taken a different approach by encouraging the winemakers to also connect with the land.

“I tell them I am a custom farmer–my grape growing is driven by the wine it will produce. I want them to come out and visit their vineyard block at least five times a year, walk the vineyard with me, discuss crop reduction, leafing, anything that will help them make a superior wine. Unlike other grape growers, I am driven by wine quality rather than viticulture.”

His meticulous work in vineyards costs a lot, Hudson explains. “The issue now with some of us grape growers is how to get larger production without losing our quality. I can’t grow grapes like growers do in Lodi because I have to maintain quality. It takes about 250 hours to farm each acre. I can’t farm at the top of my game without employees who return and understand my methods. So I provide good health care, housing and wages.

“Not only is farming expensive,” Hudson continues, “but being a farmer is ultimately a lot of work. I can’t leave my property for very long,” he tells me. “It is easier to find someone to dog sit than vineyard sit.”

Today, however, farming is somewhat less stressful than 30 years ago. Hudson gets weather data in real time, disease modules and pest materials for every situation. He prides himself on being a responsible farmer–one who understands and protects his land. As a steward of the land he farms, he provides for generous setbacks from seasonal creeks, creates buffer zones around vineyards, plants trees and provides wildlife corridors across the property.

Hudson’s intimate knowledge of his land and grapes eventually led him to want to produce his own wine. For several years he played with a blend that he liked to serve at his own home, but in 2004 he started to produce his own Char donnay and Syrah for commercial sale. In 2008, he finally added his personal house wine to the mix–the blend he named Pick Up Sticks. Each production is small, while their reputation and following are passionate.

“I am in essence a wine producer,” Hudson explains. “I am like a movie producer. I am not the director, I don’t haul hose but the buck stops here. I set the styles and parameters of all my wine. Winemaking has made me a better grape grower. What hit me the most about producing my own wines was that I actually had to pick the harvest date. I have always advised my winemakers on their dates, but now it is me in the game and I realize the pressure that they work under. It completes the circle for me to be invested in this side of the business–to have the proverbial ‘skin in the game.’ I now have so much more understanding of the process. Making wine is simple, but selling wine is hard. When you are on the street selling your wine it is a major undertaking.”

Hudson also believes that agricultural diversification is important for his land. To this end, Hudson has planted a four-acre vegetable garden on valuable land that would usually be reserved for vines. The garden supports a 50-member community-supported agriculture (CSA) harvest subscription program. In addition, he produces his own extra-virgin olive oil and he has recently planted an additional 700 olive trees. There is an ever-growing demand at top Bay Area restaurants for his chickens, guinea fowl and heritage breed pigs.

Hudson acknowledges that everything they do on the ranch requires a special skill set and that it is a daily challenge. He also seems to love that challenge. As he escorts me onto the veranda, he confides that he has three barrels of vinegar aging in his garage, that he is making 50 cases of sparkling wine for his 30-year anniversary party and that he may start a CSA for his cattle operation.

His friends and others in the wine and food industry know that, whatever Lee Hudson does, he is always striving for the very best. In his grape farming, making of his own wine and with his many other endeavors, he goes beyond what anyone else has tried. “Though I am not sure that Lee knows it,” states the Bedrock Wine Co. website, “many a person, upon entering this piece of land, deems this ‘Hudsonia.’”

One of the things that is most striking about Hudson Ranch is that there is nature in every direction–ponds, oak woodland and wildflowers. It is a bucolic property landscaped by undulating, rolling hills dotted with a sea of grapes. Late in the afternoon, we drive along a narrow dirt road that meanders through streams and grassland under the watchful eye of jet-black cattle, hawks and rabbits.

“What the hell!” Hudson shouts as he brakes, and I look to see that ahead of us are three flags flying: the California Bear, the Stars and Stripes and a third flag–that of his own home state of Texas. The third flag is twisted around its flagpole. Hudson jumps out and lowers the beloved flag and brings it with us to be repaired back at the ranch. That one gesture encapsulates Lee Hudson: his traditionalism, perfectionism and his quirky sense of individualism. Those qualities, applied to all of his hard work on this unique piece of land, are turning out some jaw-dropping, rock-star wines, along with some other highly sought after bounty.