With Fire in Their Bellies

BAY AREA CHEFS AND FOOD COMMUNITY NOURISH THOSE IN NEED DURING THE 2017 WINE COUNTRY FIRES

Whenever the wind starts to howl now, Kelly Smith reflexively tenses. It’s enough to bring her nearly to tears, as the terrifying memories of fleeing her Santa Rosa home in the dark of night come flooding back.

It was such a gale force that roused her shortly after midnight on October 9, 2017, so fierce that it felt as if the roof of her 1950s house might shear off. “It was an ungodly wind like I’d never experienced before,” says Smith, 47, the executive director for Agricultural Community Events Farmers’ Markets, which operates nine markets in the North Bay. “It was devil wind.”

One that would eventually stoke monstrous infernos in Sonoma, Napa, Mendocino, Lake and other North Bay counties at unfathomable speed.

Peering out a window, Smith at first saw only “a pink glow like a sunrise.” Her concern grew as she saw her neighbors packing their cars. “The smell of smoke was intense,” she recalls, when she stepped outside. “The glow was getting brighter and brighter. I was getting more freaked out.”

She hurriedly woke up her fiancé and his 14-year-old son. Along with their kitten, Marvin, they climbed into their car at around 1am. After seeing others hightail east, only to be turned back by flames or downed trees, they decided to try escaping west, not knowing what awaited.

Despite flames coming within less than a mile of their home, Smith and her family consider themselves fortunate among the 100,000 North Bay residents forced to evacuate in what was California’s most destructive fire season ever recorded. They not only survived, making their way to Novato to wait out the fires, but sustained no loss of property.

Still, undoubtedly like so many others, Smith suffers from bouts of post-traumatic stress following that harrowing night when more than 20 blazes erupted in eight counties. As many as 10,000 firefighters would battle the conflagrations. By the time the last one was doused, 43 people had perished, upwards of 9,000 structures had been destroyed, at least 245,000 acres had been charred and more than $9 billion in losses were sustained. Among the Wine Country landmarks incinerated were Willi’s Wine Bar in Santa Rosa, the Hilton Sonoma Wine Country hotel in Santa Rosa, the Fountaingrove Inn in Santa Rosa, Signorello Estate winery in Napa, and Paradise Ridge winery in Santa Rosa.

EVERYONE MUST EAT

It might have been one of the worst disasters to ever befall this region. But it also spurred the best of humanity to reveal itself in full force. With near-lightning speed, friends, colleagues, farmers, chefs, businesses and complete strangers all over the Bay Area began mobilizing to help in any way possible—be it offering a spare bedroom to those evacuated or now homeless, donating clothes for those who bolted with nothing, dropping off fresh fruits and vegetables to emergency shelters, volunteering to assemble hundreds of sandwiches for hungry families or raiding their restaurant walk-ins to nourish first responders running on fumes.

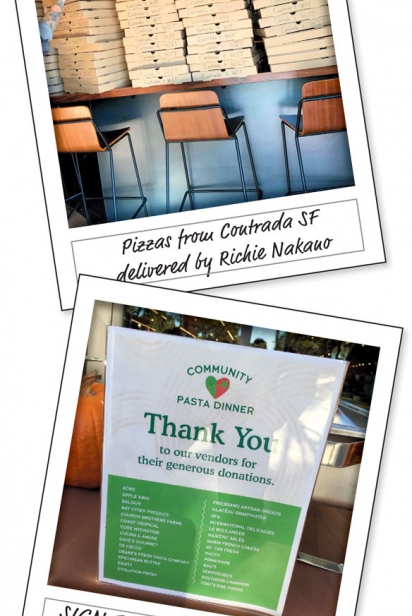

Richie Nakano of IDK Concepts pop-ups was among the chefs who jumped into action immediately. As the smoke drifted south to San Francisco and Silicon Valley, turning the skies ashen, he packed his car with food, clothing, toys, cell phone chargers and Target gift cards, then drove from his home in San Francisco to shelters in Petaluma and Santa Rosa, sometimes twice a day, for a week. He would post on social media what was needed, and responses would flood in immediately. San Francisco restaurant Aster prepped 100 pounds of beef stew for him to pick up; Tartine Manufactory had 100 loaves of bread to give; Contrada SF baked 100 pizzas; and Fine & Rare whipped up tuna salad. St. Helena’s Press made a mountain of gourmet sandwiches.

“Everyone I knew was asking what they could do to help, whether it was a high-end or a casual place. It was inspiring to see so many selflessly giving all that they could,” says Nakano, 38, who brought his two sons, ages 5 and 7, to help deliver the pizzas. “Chefs like to take care of people, and are generally in a state of crisis anyway. We’re uniquely prepared to deal with things like this.”

DESTROYED FARMS

Janet Leisen, 62, and her husband, Corrie, 63, had no idea any of this was happening. The night the fires started, they were sound asleep on a cruise ship in the Atlantic, looking forward to a weeklong respite after a busy season harvesting tomatoes, melons, peppers, eggs and honey at their Leisen’s Bridgeway Farms in Santa Rosa. Having retired from being a dental hygienist and dentist, respectively, the couple had dedicated themselves to a shared passion for farming, selling their bounty at farmers’ markets in Sonoma County, as well as to local restaurants such as Sam’s Anchor Café in Tiburon.

They woke with a start when one of their daughters, who lives up the road from them, called, frantically asking what they wanted saved, as she was driving to their house to get what she could. After friends started texting them that Kmart in Santa Rosa had been obliterated, Janet managed to contact a worker on their property, whom she asked to text her photos of their 8½-acre farm. What she saw made her gasp: “We were pretty sure at that point that everything was gone.”

After disembarking the ship when it docked in Florida the next day, and catching a flight back to the Bay Area, they made their way to Santa Rosa with trepidation. It would take three more days before emergency crews would allow them back onto their property. That was when their worst fears were realized.

`The Leisens discovered their four-bedroom home had burned to the ground. Also destroyed were a two-bedroom rental house on the property, as well as three barns, two hoop houses and one greenhouse, which had contained 100 pounds of garlic and all of the seeds that were to be planted in spring 2018. One of the barns had stored family heirlooms, including photos, and a 1919 touring car Corrie had lovingly restored. All were embers now. Only 45 chickens survived; 155 others, including her breeding stock, had died. Their cat was safe, but badly burned. Irrigation systems and fences had melted, leaving any crops that survived not only without water but vulnerable to predators. With the future of the farm in limbo, they made the painful decision to lay off three full-time employees.

The Leisens, who at the time I spoke to them were living in a trailer on a relative’s property, plan to rebuild their home and to replant in the future. After all, farming is in their blood, dating back to Corrie’s great-grandfather who staked his Sonoma County farm in 1870. But at their age, the Leisens acknowledge, they may not have the fortitude to manage such a large farm again.

“I feel like I lost everything that is me. It’s devastating,” Janet says. “You feel like you have a phantom house, like it’s still there. You are just numb.”

EVEN THOSE DIRECTLY AFFECTED HELPED OTHERS

Husband and wife Tuck and Boo Beckstoffer understand that sentiment, even if they consider themselves far luckier. Owners of Tuck Beckstoffer Estate, they were relieved that their main St. Helena home was spared. But a three-bedroom house on their 300-acre Soda Canyon ranch where guests often stayed was leveled in the fire. When their 12-year-old and 10-year-old children saw the charred property for the first time, they told her, “Mom, it’s going to make you cry.”

The Beckstoffers’ personal account of the fires, including Tuck’s first night run back up to Soda Canyon, is told by Boo in this issue. “We have all seen pictures of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the atomic bombs,” he says about viewing the aftermath of the fire a day later. “That’s what it looked like.”

From his own experience battling wildfires in Southern California, he also knew what would go a long way to help: proper provisions for the thousands of firefighters now trying to save the surrounding communities. “Firefighters are on 25- to 30-hour shifts, and when you’re in the middle of nowhere, the food is really bad,” Tuck says. “I remember eating MREs and just horrible lunches. What we wanted to do was to bring really good food out to the front lines to the guys who wouldn’t have gotten anything at all.”

Read about how the Beckstoffers’ St. Helena home became ground zero for exactly that in Boo’s account. “The biggest comment was, ‘How in the hell did you get out here?’” Tuck says, estimating that they helped provide meals to 3,000 first-responders. “Part of the fire crew is made up of convicts, and you’re trained not to talk to them. But I convinced the guys in charge of that crew to let us feed them. I don’t think they’d had food like that in who knows how long.”

KOBE STEAKS, LOBSTERS AND CAVIAR

Chef Dustin Valette, owner of Valette’s in Healdsburg, also was uniquely attuned to the necessities of the situation. His mother is a retired pilot for REACH Air Medical, and his 76-year-old father, who has been a pilot for 38 years with the state Department of Forestry, was called to duty when the NorCal fires erupted.

“There are 17 tankers for Cal Fire. Growing up, I would hear about a big fire in Eureka or Yosemite, and see all the planes swarm to it,” he says. “This was the first time that everyone swarmed here.”

Because this would be no quick operation, he knew instantly how he could best help. “What usually happens is that they take one of the firefighters and make him the cook for the other firefighters, so they have food when they get back from their shifts,” Valette says. “What we did was replace the firefighter who would normally be cooking.”

With his upscale restaurant closed that first Monday after the fires ignited, and no deliveries getting through, Valette scoured his pantry to cook what was at hand. In this case, it turned out to be Kobe steaks, lobsters and caviar.

He dropped off enough food for 150 at the Healdsburg Municipal Airport, which became the home base for the smoke jumpers who leapt out of planes with shovels right into the thick of it all. The next day, when Valette came back bearing more food, “It was like a piñata had opened up,” he says. “Everyone came running over wanting to say thank you. People were blown away. It was such a gift to give them a moment of normalcy after their long, life-threatening day.”

Even after his restaurant reopened three days later, the 37-year-old chef continued to arrive at 6am to make food that would be delivered to fire departments or evacuation centers, taking a break only for a short nap, before returning in the evening to cook for his own dining room patrons. Indeed, for the first few days, it was just him alone in his kitchen, doing all the cooking for evacuees and emergency workers because he didn’t want to burden any of his employees, who were anxious enough about their own families’ safety.

After a couple days, though, colleagues took notice and started coming by to lend a hand. They included chefs Duskie Estes of Zazu Kitchen & Farm in Sebastopol, Scott Romano of Dry Creek Kitchen in Healdsburg, Dominca Catelli of Catelli’s in Geyserville and Timothy Kaulfers of Arista Winery in Healdsburg. Together, they grilled steaks, roasted pork loins, simmered cioppino, and braised chicken with heirloom tomatoes from Valette’s restaurant garden.

BAY AREA EFFORT

All around the region, chefs and organizations were answering the call to arms. Michelin two-starred Chef Dominique Crenn marshaled volunteers to assemble 1,000 cheese sandwiches at her Petit Crenn. Napa’s Ca’Momi Osteria delivered 1,000 meals to shelters, and distributed 600 certificates for complimentary meals at the restaurant to those who had been displaced. The Ceres Community Project, a Sebastopol nonprofit that provides food to those who are critically ill, donated to shelters more than 12,000 meals made by their trained teen volunteers.

SF Fights Fire, a coalition of 650 volunteers and 250 restaurants, provided 35,550 meals over 17 days. Led by Stuart Brioza of State Bird Provisions and The Progress, Matt Cohen of Off the Grid, Ravi Kapur of Liholiho Yacht Club, Sam Mogannam of Bi-Rite Market, Craig Stoll of Delfina and Traci Des Jardins of Jardiniere, they quickly created a website so that chefs could go online to see what was needed. Copia, a San Francisco tech company focused on reducing food waste by collecting donations of leftovers, made the rounds to pick up what the chefs made, then transported it to Bon Appetit Management’s catering kitchen in the Presidio, overseen by Des Jardins. There, drivers would haul the prepared meals to the Salvation Army and community centers in the North Bay.

The chefs were told to prepare 100 portions at a time. Some went so far as to prepare three times that amount, Des Jardins says. The fare included frittatas, braised short rib pasta, chicken enchilada casseroles, beef Bolognese from San Francisco’s Lord Stanley and a memorable duck lasagna from Thomas McNaughton of San Francisco’s Flour & Water. SF Fights Fire only ended their efforts after Facebook jumped in to pledge the delivery of 5,000 meals three times a week.

“I had never seen a crisis firsthand of this epic nature,” says Des Jardins, 52. “My son goes to school in Santa Rosa. I have a house in Sonoma. This was very personal to me. These are our farmers. These are the vintners we buy wine from. This is home—or very close to it. I just wanted to dive in and help as much as I could.”

LONGLASTING LEGACY OF CARE

So did Heather Irwin, 47, who in the process discovered a new calling. The Sonoma Magazine staff writer, founder of the BiteClubEats food blog, and Santa Rosa resident of 14 years, was used to reporting on the news. But during the fires, she became the news.

Her husband, two kids, parents and 92-year-old grandmother had fled to a friend’s farm in Sebastopol. “All 11 of us were sitting at a table, wondering how we would feed ourselves,” she says. “We were all traumatized. We went to the store to buy things but it didn’t really feel like a meal.”

At the same time, many chef acquaintances were reaching out to her, asking how they could lend a hand during this catastrophe. That’s when the genesis for what would become Sonoma Family Meal came to her.

She ended up overseeing an army of chefs, culinary teachers, farmers and producers. They took in vast amounts of donated food that was prepared quickly in donated professional kitchens in Santa Rosa including Franchetti’s restaurant and John Ash & Co.’s catering facility, to serve upwards of 3,000 portions of food to-go for families in need.

“It was like a TV game show every day,” Irwin says. “Chefs would see what came in, and then scramble to make something.”

Terri and Mark Stark may have lost their Willi’s Wine Bar, but they sent their catering chef to Irwin’s operations to cook for weeks. Tracey Shepos Cenami, chef at Kendall-Jackson in Fulton, sent over lamb couscous, seafood risotto and vegan curry. Kyle Connaughton of the rarified SingleThread in Healdsburg brought over pans of lasagna.

Irwin’s 14-year-old daughter ran the kitchen some days, while her 20-year-old son helped prep. Her mother decorated tables with flowers, and gave out hugs. “I would break down crying when I saw people I knew getting in line for the food,” Irwin says. “They felt embarrassed coming to get food. It was very emotional for people. Most wanted to talk and just have someone listen. A big part of what we did was just be there for them.”

She made a point to not turn anyone away. “We didn’t want to ask a lot of questions. It was just important to get the food out,” she says. “We had people from Coffey Park. We had people who were homeless. We had people with disabilities, who had fallen through the cracks. It made me realize that there is a big hunger problem in our county beyond the fire victims.”

That’s why even after a month’s leave from her job to spearhead Sonoma Family Meal, Irwin hasn’t stopped yet. She plans to turn the organization into a bona fide nonprofit to serve area families in need for the long haul, all the while continuing her work as a food writer.

“It’s made me realize that things like food justice and bringing good food to everyone is my problem,” she says. “Being on the front lines changed me forever and made me want to be more of an activist.”

NOT JUST FOR PHOTO OPPS

Food Network star Guy Fieri was moved and motivated, too. Even so, when the spiky-haired host of “Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives” and long-time Santa Rosa resident set up mobile barbecue smokers at the Veterans Memorial Building in Santa Rosa to feed thousands of evacuees and first responders, he took a bashing on social media for bringing along a camera crew.

Fieri declined to comment for this story, but Nakano came to his defense straightaway, saying “Everyone loves to pick on Guy. But he was there, and he was cooking, and he kept cooking even after the cameras left . If someone is doing good, there’s not much you can criticize them for.”

HIGH-PRICED DINNERS RAISE BIG MONEY

Even after the fires were extinguished, efforts didn’t cease. Four of Wine Country’s most revered chefs—Thomas Keller of The French Laundry, Christopher Kostow of the Restaurant at Meadowood, Connaughton of SingleTh read and Stephen Durfee of the Culinary Institute of America at Greystone—joined forces to create a lavish dinner in December at the CIA costing $2,500 per person. Proceeds went to nonprofit Tipping Point’s Community Emergency Relief Fund, which supports low-income families affected by the fires. ChefsGiving, a grassroots Bay Area organization of restaurants led by radio and TV personality Liam Mayclem, held a gala and a week of fund-raising in November, amassing about $750,000 for Tipping Point. Chef Tyler Florence, a Marin resident, teamed in November with farm-dinner caterer Outstanding in the Field to create an astonishing “The Grateful Table Benefit,” in which 500 guests were seated at one 504-foot-long table positioned right on the Napa-Sonoma county line. All proceeds from that dinner—with tickets at $500 per person—were donated to local disaster relief organizations.

Clif Family, whose St. Helena winery, tasting room and vineyards were unscathed, contributed $1 million in monetary and product donations to those in need through its Clif Bar & Company. Petaluma’s Bellwether Farms matched $25,000 in donations to turn over a $50,000 check to the Redwood Empire Food Bank of Santa Rosa.

Whole Foods Markets, which has five stores in the affected communities, collected more than $142,000 in donations from customers for the Red Cross, made its own $100,000 Red Cross donation and gave $10,000 to the Sonoma County Resilience Fund. It also hosted free spaghetti dinners at its Napa, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Petaluma and Sonoma stores for anyone in need of sustenance. The markets also partnered with four local brands—REBBL, Revive, Zupa and Invo Coconut Water—for a month-long promotion in which 25 cents per product sold was earmarked for the Sonoma County Resilience Fund. All in all, with Whole Foods matching the contributions, a total of $20,000 was donated to the fund from the promotion.

Slow Food Russian River held a “Beans, Beer and Bangers” fund-raiser in November for Tierra Vegetables, grower of heritage beans and corn in Santa Rosa, which lost half of its local customer base in the aftermath.

REBUILDING COMMUNITIES

The Agricultural Community Events Farmers’ Markets suffered a marked dropoff of customers, too, Kelly Smith says. Besides market vendor Leisen’s Bridgeway Farm, the popular Bee-Well Farms in Sonoma also was destroyed by the blaze, and many more farms suffered losses of crops, barns and equipment. There’s no telling if all of those affected will be able to replant this spring.

For these farms, businesses and communities, rebuilding will be an unfathomable process. Still, they are pressing on determinedly. The fires might have snuffed out much in their path, Smith says, but the flames did not extinguish the region’s indomitable spirit.

“The people who lost everything are grateful that they are still here. Others feel guilty that they were saved,” she says. “We’ve been set back. But I think we can come back, and there will be more strength in what we do.”