The First of September

“For us hunting wasn’t a sport. It was a way to be intimate with nature, that intimacy providing us with wild unprocessed food free from pesticides and hormones ... “

—Ted Kerasote in Merle’s Door: Lessons from a Freethinking Dog (Mariner Books, 2008)

It was just a few minutes past 4am and I was already late. Puffy-eyed and tripping over barely laced hunting boots, I crawled into the cab of John’s pickup truck, pulling spent shotgun shells from crevices in the cushions before settling in. My double-barrel shotgun was laid on the floor and the picnic basket rested on the backseat, its savory aromas filling the car, making John’s Labradors even hungrier with anticipation. Today, after all, is what his retrievers live for: opening day of bird season.

As we made our way further into Northern California, John, a passionate hunter, broke the sleepy silence with stories of his most recent, boysonly deer hunting trek. He scored his one allotted buck with a bow and arrow on the first day of a 10-day trip in the High Sierras. Slowly awakening in the front seat, sipping sweet green tea and looking onto the still-dark flatlands of orchards and wheat fields, I imagined John, dirty and restless, on the remaining nine days of his expedition.

We arrived into the agricultural town of Dunnigan, in Yolo County, well before cockcrow on the first of September, the official opening day of dove season, its official start a prescribed time somewhere between dawn and sunrise. In the purple shadows before daybreak, I was able to discern yards with cinderblock fences strewn with rusted farm equipment, their bent shapes and hollowed-out frames referencing an earlier age of smaller-scale agriculture.

We were there to rendezvous with a dozen men and women, several of whom worked with the California Department of Fish and Game. Enthusiastic hunters and knowledgeable environmentalists, most are able to rattle off species of trees and habitats of birds and bees before the soul in question is even in sharp focus. And each proved to be a great shot. Their respectful, thoughtful understanding of these ecosystems made me more grateful for their bounties of sustenance, more conscious of my tread.

Our motley group was granted access to private ranchlands through a friend-of-a-friend. After we had petted the hounds, thermoses of strong black coffee were passed around, a coffee klatch in camouflage. The greetings were lengthy and news-filled, as many of those gathered had not seen one another since the previous year’s dove opener.

We came for Mourning Dove, which, according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is the most frequently hunted species in North America. The Mourning Dove puffs its chest to wail a rueful whoooo-cooo-coooohooo, its smallish head resting on a bantam butterball body balanced only on the briefest of weak legs. Their coloring, from sumptuous leather brown to Mercedes silver, often flecked with grays and blacks, helps them blend into their environment; camouflage designed by Mother Nature. Mourning Doves can be distinguished from other types of North American doves by their long, almost pointed tail. And it’s important to be able to identify different types of dove, as several breeds, including Common Ground Doves, Ruddy Ground Doves and Inca Doves, cannot be hunted. California’s daily bag limit is 10 Mourning Doves or 10 Whitewing Doves, with no limits on the invasive Eurasian Collared Dove. A couple of men from our hunting party had scouted the ranch days earlier and reported seeing Mourning Doves stacked up like rush hour at O’Hare.

We scattered ourselves amongst the hundreds of acres, awaiting the first light of day. Doves depart their evening roosts at dawn in search of water and food, and soon would be overhead. I huddled into the arms of an enormous oak tree, shielding my bulky silhouette from sight. Doves spook easily, but it’s quite manageable to be completely still in the quiet solitude of this morning. Recently I read a book of essays on hunting gifted to me by one of my shooting mentors, which had an entire story devoted to the practicality of being properly clothed: layered sweaters for cold early mornings, deep pockets for shells and birds and smokes, jackets made from military surplus camo or “stick out like a sore thumb” Day-Glo orange, and finished with a brimmed hat to retain warmth or shield from punishing sun in open fields. In the chill of predawn, I buttoned my heavy hunting jacket, a hand-me-down gift from a friend who had recently traded up to a fancy English hunting coat.

I tried to acclimate my eyes, looking into the dusky light for darting birds, listening determinedly for the thrum of flapping wings, the whoosh and whistle as they fly overhead. Newly plowed fields on a neighboring farm shivered with aromas of cow manure and parched earth, and a distant screech of roosters announced the new day.

Oftentimes I return home with an empty game bag, but I hardly mind. Hunting and fishing and even playing golf have more in common than merely scoring; communing with nature, bonding with your comrades in arms (or poles or clubs), breathing fresh air and taking in the sky provide a psychic shift like no other. Nevertheless, as a Ghanaian proverb wisely counsels, “If the hunter returns home with mushrooms, don’t ask him how the hunt was.”

Immediately I regretted being absorbed in thought, as the first flight of doves whizzed overhead, their powerful wingbeats suddenly audible, only to be knocked out of the sky farther downfield by a more attentive hunter. Mourning Doves have many of the same predilections as their human counterparts in Northern California: They prefer trees to sparse landscape, a close body of water, good places to dine, a midcentury-modern space in which to roost. Come midday, doves eat sand and grit, referred to as graveling, which they find on the bare grounds of dirt roads and sand bars. These bits of gravel help the birds’ gizzards to grind up and break down seeds.

As the red brushstrokes of sky changed to orange and then pink, morning came quickly. Thumping of gunfire, both near and far, signaled the arrival of dove, ironically the bird of peace, as many appalled friends reminded me for weeks prior. As I shouldered my 20-gauge shotgun and sighted dinner, a deep ambivalence for hunting coursed through my veins. Pushing through this darkness, my fear and heartache were shaped into a melancholic comfort at the ability to commune with the natural world by foraging for food.

Wait for it.

Don’t get anxious.

Stay present.

A blur of flapping wings edged closer: 50, 40, 30 feet from the tip of my shotgun before I pulled the first trigger, then the second. Two bullets were launched, each loaded with number eight shot, which contains hundreds of tiny steel pellets that spew across the sky. This shot has a shorter range, but it takes just a few pellets to bring down a small bird.

I took aim and shot at many more of the diminutive birds than I actually hit, although I managed to bag my limit of 10 before midmorning. Clearly excited, the dogs quickly retrieved the birds as they fell into the tall dry grasses, long before ravenous ground squirrels were able to drag them into their dark dens.

Sigmund Freud asserted that a fear of weapons is a sign of retarded sexual and emotional maturity. If he’s correct, then I had a breakthrough today, as I finally became more comfortable with my shotgun. Learning to shoot is akin to learning to drive a clutch; I stalled out as many times as birds got lucky, but eventually something clicked. Still a bit gun-shy initially, the hundred shots it took to bring down 10 wee birds left me humiliated, but finally liberated from my intimidation. And my embarrassment is shared: Field and Stream magazine reported dove hunters shooting five shells for every bagged bird.

The wafting pungent smell of good California ganja led me back to the trucks, all parked in a row and coated in a fine dust. My hunting jacket was shedding feathers, the pockets brimming with spent shells. Most of my fellow hunter-gatherers were already situated in a circle, propped on their three-legged stools, removing the doves’ plumage and trading stories about the ones that got away. Almond orchards, wheat and millet fields, and acres and acres of sunflowers surround this ranchland. The craws of the bitty birds revealed slivers of almonds and sunflower seeds; a testament to their diet and our good fortune at being able to hunt such marvelously situated countryside. While plucking and field dressing the birds, we left a wing intact on each dove for easy identification, in case Fish and Game wardens appeared to inspect our haul.

When the birds were finally picked clean and laid to rest on beds of ice, we opened coolers and picnic baskets to share our morning repast. Thinly pounded abalone from a recent dive was served alongside green and red pears picked the evening prior. Crispy fried chicken, washed-rind goat cheeses from Sonoma, and fat figs oozing their juices were offered with jagged hunks of prosciutto and cubes of green melon with basil flowers. A blackberry galette with rough edges made by a fellow hunter with his own rough edges also found a place on the tailgate. Slicing pieces of dried fennel sausage, I noticed my dirty, bloodstained hands, as much a badge of honor as purple mitts to the winemaker or dirt-caked fingers to the farmer. As bottles of cold beer and cheap white wine were drained, the stories of the ones that got away became more animated; the prey in question wilier, larger, craftier than ever before encountered, calling to mind Otto von Bismarck (1815–98) who said, “People never lie so much as after a hunt, during a war, or before an election.”

Never am I able to sit down to a meal of anything I’ve harvested on the same day I took it for the pot. The stink of death from the fish, pig, lamb, cow or bird I’ve slaughtered still lingers on my fingertips and remorse needs at least a day to resolve into gratitude.

We sat outside on an early evening, a hoarded bottle of Dehlinger Pinot awakening in glasses. With a bit of green oil and sea salt, we ate the roasted dove with our hands, the birds of peace silently savored. Each breast yielded only one, precious, crimson bite, rich with flavors of mineral and earth. Tomorrow, the carcasses will flavor pots of bird stock, the doves nourishing us long into the winter months ahead.

GRILLED FOWL

Unless you hunt or get very lucky at the butcher, both dove and squab are specialties often difficult to find. Quail is an ideal substitution, easier to locate and quite delicious. Plan on two birds per person for a generous main course.

Coat the birds in a mixture of olive oil, salt, pepper, smoked paprika peppers crushed by hand, lemon zest, honey, chopped garlic and fresh thyme and allow them to marinate for 4-6 hours, covered in the fridge.

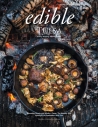

Arrosto giratoalla fiorentina is a method of cooking meat on a spit, as outlined in Giuliano Bugialli’s book The Fine Art of Italian Cooking (Clarkson Potter, 1990). As I was in possession of a gas grill but not a spit, fortunately, the book advised an improvised cooking plan: On a hot grill, place a cast-iron pot filled with 4 cups cold water, healthy splashes of wine and olive oil and a palmful of coarse salt. The marinated birds are skewered and balanced above the bubbling liquid, ensuring their moist succulence. Lower the lid over this bird banya, peeking only to touch them up with a bit of marinade. The skins’ color will eventually turn to autumn chestnut and be flecked with bits of garlic and thyme seared into the flesh. Serve next to a scoop of California wild rice cooked in mushroom broth, tossed with toasted Oregon filberts and dried cranberries plumped in port.

Author’s note: Learning to properly wield a shotgun, stone-sharpen a knife, clean a pheasant, grow a spicy radish and debone the halibut I reeled in allows me the ability to raise a fist against factory farming, to communicate with the cycles and seasons of nature, and with the unusual people who speak in the same, impassioned tongue.