Red Rocker Sammy Hagar, as Comfortable in the Kitchen as Behind the Microphone

A Little Bit Of Everything, And It Works

He may be known for his electric-socket blond curls, his sizzling chart-topping Van Halen vocals, and his devilish declaration that he just “Can’t Drive 55.”

But these days, the Red Rocker also wants you to know he makes a mean red sauce. Not to mention a wicked lobster burrito, papaya-marinated chicken and golden fried abalone sandwich.

Sammy Hagar—yes, that Sammy Hagar—is itching to proclaim to the world that he learned how to cook before he learned how to rock.

“It’s true. I didn’t rock until I was 14,” Hagar says, relaxing in his hilltop Mill Valley home with rock-star-approved panoramic views of Mount Tam. “But I was cooking since I was 4.”

The Grammy-winning songwriter and musician, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame-r and legendary front man for Montrose and Van Halen takes his music seriously, of course. But his food and drink equally so.

After all, he counts Emeril Lagasse, who catered Hagar’s wedding to second wife, Kari, and with whom he loves to cook, as a close chum along with Jose Andres, Mario Batali, Julian Serrano and Guy Fieri.

Hagar’s also savvy enough to own 10 successful restaurants, including the fine-dining El Paseo in Mill Valley with business partner Tyler Florence; to have created Sammy’s Beach Bar Rum in Hawaii; and to have built his Cabo Wabo Tequila into a leading premium brand before selling it reportedly for more than $90 million. All told, the restaurants and the spirits ventures have proven far more lucrative than music ever has. It’s not even close, he says, still in wide-eyed amazement.

Now comes his first cookbook, Are We Having Any Fun Yet? The Cooking & Partying Handbook (Dey Street Books, 2015). As the name implies, it’s not your typical cookbook, but one served with a heap of Hagar-isms and hedonism.

What other cookbook would dare discuss the virtues of damiana, a shrub otherwise known as “Mexican Viagra?” Or include a recipe for “Bud Butter?” (Exactly what you think it is, and Hagar recommends gilding a baked potato with it.) Or be penned by someone who likens his paella to sex: “It’s never bad, but it’s better when I do it. And I never do it the same way twice.”

Published this past fall, the cookbook may have its wink-wink moments, but it’s also full of bona fide recipes, such as “Sammy’s Asada,” “Braised Lamb Shanks” and the “808 Mojito,” all inspired by Hagar’s time living and cooking in Cabo San Lucas, Mill Valley and Maui, where he keeps homes.

It’s also a cookbook for which he has big dreams. Along with the MTV and Billboard awards that grace his living room bookcases, he’d like to add a James Beard Cookbook Award, too.

“Respect is a big thing. Anything I do, I don’t want to be dogged for it or underestimated,” says Hagar, 68, and a self-professed success junkie. “With the cookbook, there will be people who say, ‘He’s a rock star. What does he know?’ I do know good food, good wine and how to pair them.”

Just ask Chef Michael Mina, who first met Hagar in 2004 when he came in to dine at Mina’s eponymous flagship restaurant then located in the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco. Mina, who grew up listening to Hagar, was impressed twofold. Not only did Hagar remember years ago pulling Mina’s older brother, a guitarist, onstage to play on three songs at a concert in Ellensburg, Washington, where the Mina family grew up, but he possessed a genuine inquisitiveness about all things culinary.

“When I had on the menu the whole chicken that’s fried to order in duck fat and studded with truffles, it was a 45-minute conversation at the table with him. He wanted every detail. And he was writing it down,” Mina says.

“He’s never struck me as someone who just wanted to put his name on something. Instead, he wants to know everything about it. He once asked me how I picked my chefs, exactly what I looked for, and what skill sets I thought they needed. It was a high-level restaurant conversation.”

With a Mill Valley home kitchen done up with glossy cabinets by the same Italian design company that fashions Ferrari bodies, and a wine cellar stocked with 10,000 stellar vintages and growing, Hagar definitely bucks the stereotype of rock stars who binge on booze, drugs and junk food.

“I know plenty of guys still like that,” he says with a grin. “When I had my first fast-food burger, I loved it. I went on the road with Montrose and ate nothing but junk. I couldn’t afford anything else. But finally, I came around and turned around. I never wanted to eat like that again.”

For Hagar, food has variously been synonymous with family, love and survival—often when those three things were not easy to come by in his life. “Half Italian and half Southern redneck,” he grew up dirt poor in Fontana, California, to an alcoholic father whose abusive episodes would send his wife fleeing, with little Sammy in tow.

“She’d have to leave. We’d rent a house, and she’d iron or we’d pick fruit in season to make money,” Hagar recalls. “Mom would run out to the garden to get what she could to make dinner” for her take on “yard-to-trailer” cooking.

His Italian maternal grandfather, whom he was named after, might not have always been warm and doting, but he was a force in the kitchen. Hagar grew up watching his grandfather hunt and fish, as well as can tomatoes, roll out pasta and make everything from venison jerky to rabbit pâté.

“His spaghetti sauce was to die for,” Hagar says. “When my grandfather was really being nice, like when I first got married and was poor on welfare, he’d bring me jars of his venison meatballs and oxtail soup. I thought, ‘Grandpa really does love me.’”

Hagar, who didn’t go to college and just squeaked by to graduate from high school, didn’t grow up eating in nice restaurants. It wasn’t until 1975 when he was on tour in London for his first solo album that he had his first real taste bud epiphany. A friend of a friend offered to take him to dinner at an elegant hotel, where Hagar sat back and experienced for the first time the pleasures of peaches and prosciutto paired with Chateau d’Yquem. It was a moment that would forever change his life. It made him realize that food and drink—whether humble or haute—could be transcendent.

Buoyed by that newfound appreciation, he decided to open a tequila bar and cantina in laid-back Cabo San Lucas in 1990. He named it Cabo Wabo, inspired by the sight of a drunk wobbling down the street. It later became a Van Halen song, too.

It nearly went under in its first year, the victim of drug-addicted employees pilfering cash and shakedowns from Federales, Hagar writes in the book. But he started performing shows there to keep it afloat. Its success led to three other Cabo Wabos: Lake Tahoe, Las Vegas and Hollywood.

There are also five Sammy’s Beach Bar & Grill locations, from which he donates his personal profits to local charities in each of those cities.

Back when he was a broke musician living in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury, Hagar had vowed that if he ever made any money, he would move to Mill Valley, a town that also had lured Bill Graham, Grace Slick, Jerry Garcia and Carlos Santana with its quaint, artsy, bucolic charms.

In 1976, he did just that, buying the house he still lives in today that’s surrounded by fig, apple, peach, orange and lime trees. He forages for morels, chanterelles and prized porcinis (to fry in butter, white wine and lemon juice)—and gets dejected whenever another intrepid fungi fanatic beats him to them. He’s also been known to cook the errant bird that’s crashed into his home’s soaring windows.

San Francisco magazine restaurant reviewer Josh Sens is the co-writer of Hagar’s cookbook, an experience he describes to his surprise as the easiest working relationship he’s ever had.

“You hit ‘push, go,’ [on the voice recorder] and Sammy has a story,” says Sens, who worked on the project for a couple of months, including evenings spent at Hagar’s house, where the rocker would cook his famed paella, roast chicken and saucy osso bucco (Hagar’s last-meal-on-earth dish). “He has very vivid memories of food. And he knows food. But he talks about it like he’s hanging around with his buddies. There’s none of that foodie lingo.”

Just what does food give Hagar that music doesn’t? “It gives me a gut, to start with,” he says with a laugh. “It gives me peace and focus.”

“Cooking is like writing a song. You make something from nothing. You take a bunch of ingredients and create something better than the sum of its parts. You get a guitar, you start a melody and you bring in drums and a keyboard. You taste it and say that it needs something. You add harmonies, and you get a beautiful song at the end. Just like a recipe.”

But don’t get the wrong idea: If given the choice to do it all over again, he wouldn’t choose being a chef-restaurateur over a rock icon.

“I had to become a rock star. I was poor,” he says. “The businesses that I went into later were expensive. I would never have been able to start a tequila company or the restaurants. It all came from rock and roll. Everything came from the music.”

That beat goes on, as do plans for other businesses—even at an age when he could be retired and living the good life.

“That’s what I am doing,” he says with no hint of irony. “Because what do you do when you’re retired? You do all the things you like to do.”

SAMMY HAGAR FOOD FACTS

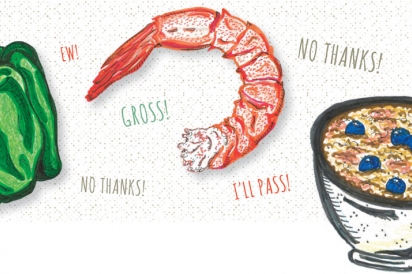

Least Favorite Ingredients: Green bell peppers, oily fish, oatmeal.

What He Abstains From Before Concerts: Shrimp, because it swells the vocal cords; and red wine because it dries the throat.

Dish That’s Most Like His Personality: “Paella. It’s got a little bit of everything, and it works.”

Biggest Cooking Triumph: Cooking risotto at his home for Chef Julian Serrano. Hagar fortified it with veal stock and cream, and topped it with chopped veal seasoned with chili flakes and rendered down for hours until the meat was a little crunchy. He paired it with a 1978 Cheval Blanc and a 1985 Conterno Barolo. So impressed was Serrano that he’s recounted the experience fondly to others.

Chef He’d Most Like To Cook With But Hasn’t Yet: Jose Andres.