Sayulita Daydreaming

DROPPING A LINE ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE WALL

The customs officer at the small, modern airport in Puerto Vallarta eyed me up and down, his pressed blue uniform thrown off-kilter by three-day stubble and dirty fingernails. Piecing together his gestures with a couple of words snatched from his rapid-fire Spanish, I gathered he wanted to know the contents of my luggage, which included a densely taped brown shipping box. Reflexively, the top of my lip broke into a sweat, flushing through my entire body until my linen dress was soaked.

In halting Spanglish, I explained that the luggage was packed with bathing suits and sarongs, soy sauces, sesame and olive oils, enough reading to be shipwrecked for a year, fileting knives, Japanese chili powder Shichimi Togarashi, a sharkskin grater (for the undeclared wasabi root), a loaded tackle box, tea and honey, a case of wine.

Ah, yes, the wine.

At the mention of the word, the officer’s bushy black eyebrows immediately shot upwards. Yes, indeed, he needed to collect duty tax on the wine. How much was each bottle worth?

Several pesos paid on a credit card later, we rolled out of the terminal into a brightly colored wall of blazing heat, its thick, unyielding humidity wilting me like a Mexican dahlia in stale water. The waiting van, its windows lacy with condensation from the blasting air, produced re-invigorating goosebumps and icy mini-bottles of Mexican beer were fished from the depths of a red plastic cooler resting on the front seat, their petite size ensuring each of the three gulps cold and refreshing; a splendid introduction to how to beat the unrelenting heat.

It wasn’t long before we spotted a dozen red umbrellas shading folding tables, tucked into a tight corner of the forested road cutting to the coast. Anywhere on the globe, a stop at a roadside stand rewards with bits of insight into local culture while filling the vehicle with regional plums: Tropea onions in Calabria, strings of chiles in New Mexico, chickpeas in Egypt, crocks of smoked bluefish pâté in Rhode Island, dried shrimp in Thailand.

In the shadow of gigantic palm trees, their fronds still in the languorous heat, our totes quickly sagged with papayas and watermelons and burlap sacks of local sea salt, both fine and coarse. Coconut water slurped from its shell helped us acclimate, the nut’s hard exterior opened by a grinning, machete-yielding boy, a tree trunk his butcher block. Bags and bags were filled with limes the size and texture of golf balls, their distinctive green juice to flavor morning teas, afternoon margaritas, evening ceviches. A brawny middle-aged woman, deeply lined and sporting a red bandana around her neck, nodded in my direction, offering slices of warm mango, its resinous-sweet nectar ripe, juicy, sexual.

Our chilled cocoon made its way farther north to the village of Sayulita on Mexico’s Riviera Nayarit, a 200-mile stretch of Pacific coast-line. With the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains at its back door, Sayulita is a funky, relaxed beach town of 4,000 full-time residents, who are joined in winter by hordes of gringo hippies surfing the warm waves. Our small coterie, however, opted to visit in the quiet, slow roast of a Mexican summer, our only agendas to fish, read, swim and drink tequila.

DayGlo pink stairwells lined with cacti and succulents ushered us into the heart of the town, and our noses immediately guided us to an open-air taqueria. Equaling the weather in Scoville-scale torridity, smoky shredded pork was tucked into tortillas made a la minute by an old lady in a T-shirt touting English profanity, the letters written in red sequins.

Hands and arms sticky from melting papaya and kiwi paletas, traditional Mexican popsicles made from tropical fruits, we meandered the central plaza in a sweaty, heat-induced trance, hewing closely to the thickly stuccoed yellow and orange buildings for every ounce of shade. Passing a couple of dodgy bars to which I vowed to return, we ducked into artisans’ shops offering textiles and crafts from the Huichol people, an indigenous tribe whose celebrated works include intricate paintings made with brightly colored yarns and beadwork pressed into layers of wax. Cow skulls are often adorned with this artistry, forging beauty onto death. Colorful pompoms, a traditional Huichol frill, are hung throughout town, and even Sayulita’s cemetery is dazzling with color, reflecting the radiance of the human spirit.

Despite the weight of heat and humidity, there’s a vibrancy and glow to the town, with glimpses of eye candy in unlikely places: a quiet corner down a brick alleyway blooms with magenta bougainvillea and elaborate birds of paradise, their plumage an Isabella Blow chapeau. The dense air is punctuated with aromas of jasmine flowers, the brine of the omnipresent Pacific, and an unctuous, fetid decay: the humid heat rotting food into garbage with surprising rapidity.

Delivering pyrotechnics rivaling a Kiss concert, a spectacular thunderstorm blew in from the north in the early evening, pulling the plug on the town’s electricity. Lightning strikes lit up the ocean as if midday, no doubt confusing the sea creatures below, while rolling thunder bounced off the mountains, its claps silencing even the chatty chachalaca birds residing in the nearby jungle, their calls oddly reminiscent of my former mother-in-law.

Over the blaze of candlelight and in between sips of tequila, we optimistically rigged fishing poles with heavy nylon monofilament line, hoping to score a good fight with a dorado (mahi-mahi), a metallic blue-green fish growing to 80 pounds with the moves of a Russian gymnast; or a similarly huge roosterfish roaming near shore (the world record of 114 pounds was caught in these very waters); or maybe a pargo (red snapper) looking for a fight, a welterweight in the game fish world.

As much I’d like to see a Pacific sailfish, which can reach more than 200 pounds, or a blue or black marlin at 1,000 pounds, I couldn’t bring myself, either physically or spiritually, to reel in such majestic creatures. The days of Hemingway, big game trophy hunting, and gin at lunch belong to a different moment in time. Our seas tapped and fish stocks depleted, we take only what we’re able to eat and share with neighbors.

While I would be grateful to keep most any tasty fish that had the misfortune to take my bait, in truth, it was amberjack I craved. Its firm flesh the pale pink of a Turner painting, this fish is delicious both raw and cooked. Not to mention that it’s an accomplishment to reel in an amberjack, as they’re powerful fighters with great stamina, making the fisherman work for her dinner, arms aching with pleasure.

We debated lures while attaching weights and hand-forged Japanese carbon steel hooks to our lines. As we tied knots, I wondered how different our evening preparations were from those of the local fishermen 100 years ago. Back then, fishing line was made from silk, linen and cotton and had to be carefully, laboriously unspooled after returning home from a day’s work to be washed and laid out to dry thoroughly to prevent rot. But perhaps our evenings were not that different: I’d bet many of those long-ago anglers threaded their fishing poles by candlelight in between sips of the local hooch while arguing about the best methods to hook fish, as well.

We set out before sunrise, packing onboard our poles, tackle, water, coffee Thermoses, fruit and salty snacks. Captain Enrique, a native who’s fished the Pacific from Central America to Alaska, soon tied up his comfortable fishing boat to a panga floating quietly on flat waters just outside the harbor. Barely bigger than a Boston Whaler and a whole lot less posh, the panga is an open, modest-sized, outboard-powered fishing boat common throughout much of the developing world, without even a cover to shield its passengers from the unabated sun and pounding heat. The man aboard the panga had been jigging all night to catch the small baitfish Enrique now bought. As we motored away, he explained it’s common for one or two men to navigate a panga 100 miles or more into the open ocean to hook tuna and sailfish with nothing more than a line and a club, tossing the large, capricious fighters into a massive ice chest on the floor of their small boat.

Noiseless pods of porpoise and dolphin greeted the morning, their skin the color of wet slate. As the sun rose in the sky, schools of small fish leaped out of the water only to be feasted on by sea birds, who delicately picked them out one by one; pelicans gobbled up as many as their cavernous maws could manage. We slowly trolled the waters, lines kept long to bob along the surface, while making our way to deeper seas. We fished reefs and rocky outcroppings, dropping weighted lines into bottomless clear waters.

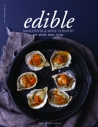

Our haul was just generous enough to provide dinner. We fileted three smallish yellow jack and two very handsome triggerfish, their skin as tough as rubber and stubbornly resistant to even my newly sharpened knives. Fish bones were put into a stockpot and covered with water and wine, creating the rich base for a fiery fish stew. The filets were chopped and tossed with finely cubed red Serrano and orange Habanero peppers, sweet white and hot red onion, a mound of fragrant cilantro, Mexican sea salt and the juice from a dozen limes. Fresh corn tortillas, made in town earlier in the day by a young woman with a nose ring and Tibetan tats, were fried and christened with salt.

Sunburned and salt crusted and still slightly rocking from being out at sea, we sat silently in the twilight, listening to distant thunder and scooping up mouthfuls of spicy ceviche with the crispy chips, cooling our burning lips with cold Pacifico beers and margaritas served in coupes a Mexican Marie Antoinette would appreciate.