$15 A Cup?

Marin Roasters Set a New Standard for Coffee Excellence

Early last February an A-frame sign went out on the sidewalk in front of Equator Coffee & Tea’s Warfield café in San Francisco advertising a $15 cup of coffee. Shortly afterwards the Bay Area Twittersphere was abuzz—but for only a few of those lucky tweeters was the high off the actual premium-priced caffeine. The café sold fewer than 20 cups before it ran out; the beans themselves, priced at $75 per half pound, sold out online in less than a day.

After Buzzfeed broke the story with a predictable series of memes, and the rest of the internet quickly confirmed that San Francisco’s $4 toast problem was just the first sign of the hipster-driven apocalypse, local food writers eagerly rushed to the café. Somehow each one reported that they got the last cup, and details emerged about why this particular eight ounces came at such an unusually high price.

The $15-a-cup Finca Sophia coffee was crafted from the inaugural harvest of Equator’s coffee farm in the Panamanian highlands. About a decade ago, Equator’s co-owners Helen Russell and Brooke McDonnell invested in a plot of untamed land, planting one of the most hard-to-grow, sought after coffee bean varietals at an extremely high altitude. It was an experiment, one with a mission to grow the best possible coffee in the world—in terms of quality and environmental and social impact—and took years of setbacks and a lot of seed money before this first small harvest. As reported in the Winter 2013 issue of Edible Marin & Wine Country, the coffee farmers at Finca Sophia are very well compensated and also provided with quality housing, means for education and health care for themselves and their families. Do the math after over eight years, and Equator made little money, if any, off this harvest round—even at $15 a cup.

What Equator did make was an opening for the media and consumers to discuss what defines “value” when buying a cup of coffee. Is it purely affordability? Taste? Low environmental impact? An ethical supply chain? And when you combine all those elements, when a cup exhibits the highest quality standards, unparalleled flavors, is grown sustainably and provides fair compensation for farmers, how much should it cost?

Ironically, the name left out of that press storm was one of the people obsessively studying some of the most urgent questions in the coffee industry—and the other half of the Finca Sophia partnership. That person is Willem Boot, a coffee quality consultant and coffee farmer based in San Rafael. When Finca Sophia won a Good Food Award earlier this year, Boot was also nabbing two more of the coveted awards for coffee lots from his other farm, La Mula—but unless you’re in the business, up on which baristas get their beans from whom, you wouldn’t have any idea. It was a quiet victory for a man who’s spent his career chasing the perfect cup of coffee.

Boot says his love story with coffee began in Holland, where his father opened the country’s first shop focusing on freshly roasted single-origin coffee. This was in the 1970s, when most coffee in the Western word was commercially sourced, roasted and blended— strictly a utilitarian beverage. It was then, as a 14-year-old shopkeeper, that Boot mastered roasting, cupping and the lingo that most of us still make amateur attempts at while trying to engage with baristas about flavor notes.

Boot continued to move deeper into the coffee world, working for a roasting machine manufacturer in the U.S. and learning from some of the industry’s coffee pioneers. In the early ‘90s, having taken over the family coffee business, he and his brother set up their first direct trade partnership with farmers in Panama.

By 2000 Boot had established himself as a consultant, helping participants at every level of the coffee supply chain improve quality. He and his team offer roasting, tasting and grading courses, consulting on everything from the green bean to the roasted product, and conducting market research for international coffee organizations.

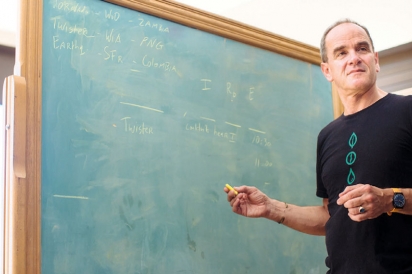

In June, I sat with Boot at his near-ready coffee campus and R & D center just across the neighborhood baseball field from Equator’s roastery in San Rafael. The campus will take his business to another level, layering in certification opportunities, bringing in more students, providing a wider variety of programs and hands-on training with equipment and offering a direct connection to farmers that doesn’t exist elsewhere.

Boot has a charming smile, worry lines on his forehead, and immediately offered me a coffee. We carved out space on a high table next to the ladders and shiny machines, and he poured me a small glass cup of his award-winning lot.

“The underlying vision [for Boot Coffee Campus] is a center for innovation and quality research and training for the Pacific Rim, and that’s not based upon our desire, but based on demand from our clientele,” said Marcus Young, the venture’s senior trainer and quality advisor, who says they see an average of 1,200 students per year already.

While quality improvement strategy is clearly Boot’s bread and butter—and utilizes his degree in business economics and his in-depth coffee knowledge—it’s talking about the coffee in front of us that gets him excited. He lists off forest flower notes, teaches me to direct air in or out of my nose as I take a sip, and passionately recounts his first encounter with this varietal.

In 2004, as a judge at the Best of Panama Cupping Competition, Boot (and much of the coffee industry) tasted Gesha coffee (sometimes also referred to as Geisha) for the first time. “That year was a dark time for the coffee industry,” he said. World coffee prices had collapsed in 2002 to a 30-year low, putting already vulnerable small-scale coffee farmers at a crisis level. Thousands of jobs in Mexico and Central America were lost as coffee farmers laid off workers or abandoned their farms altogether.

“And then, here was this family with this coffee; it tasted like citrus at first, then floral, rose, papaya and honeysuckle and lime. They blew away all the tasters and blew all the records for prices.” He gave it a rating of 96 points, and the coffee sold for five to 10 times the market price. It’s still one of the most expensive beans on the market.

“I was intrigued, but also nervous and anxious that I would never be able to reproduce that flavor myself and that I would always be dependent on other producers,” he said. I imagined it like falling in love after a first date, followed by the heart-wrenching thoughts of it being unrequited.

“And then I thought to turn that desire to an idea,” he said.

He went all in a few years after that, buying five hectares of land 1,800 meters above sea level on the slope of a volcano and starting a coffee farm. In the absence of roads, the coffee seedlings and equipment were transported by foot and mule through the rainforest, inspiring the farm’s name, La Mula. Working with a team of 15 indigenous farmers, they produced the first harvest in 2014.

Gesha was originally an Ethiopian coffee first picked in the 1930s in the mountains of western Ethiopia, near the town of Gesha and not far from the Sudan border. The plant journeyed through Tanzania, Kenya and Costa Rica, taking on new genetic characteristics at each stop and eventually landing in Panama. There, a small group of farmers planted the coffee in different plantations in the Chiriqui province, home to highland rainforests and the country’s most productive agricultural fields. It spent the next 40 years in relative anonymity before it turned heads in 2004 and earned holy grail status for coffee buyers.

I was not surprised to learn that Boot made several journeys to Ethiopia in an attempt to understand the origin of this uniquely sought-after bean. Part of Gesha’s allure (and price tag) is how complicated it is: It’s a fragile varietal with a high rate of failure, easily susceptible to fungus, and needs to be carefully and minimally processed. It’s no wonder a quality guru went nuts for it.

It was Boot’s international reputation in the industry, his relationships with local farmers, and personal experience of owning a Gesha farm himself that made him an attractive partner to Equator.

“There’s no starting any type of project without collaboration and connection to local people,” said Equator’s co-founder McDonnell. “We were thinking about doing it ourselves, and then Willem heard about it and he went and took a look at the land with us and said ‘I think we can grow the best coffee in the world here.’”

Equator’s plot was a few thousand meters higher than La Mula, putting the plants at a greater risk of burning from UV rays and exposing them to a level of wind and cold that can cause disease. It was a big experiment, but with high risks come high rewards: In theory, the quality of coffee can increase by cultivating the plant at higher elevations, and a pattern of warm days and cold nights will slow down the maturation cycle of the coffee cherries, making the oils in the beans (and therefore the aromas and flavors) more complex.

After 10 years, McDonnell said, the farm is finally closing in on being self-sustaining. It’s planted with hundreds of shade trees, along with the thousands of coffee plants, to create a buffer between the Parque Amistad Internacional and the largely unforested agricultural areas surrounding it. Six workers and their families, all from the Ngobe Bugle indigenous group, work and live on the farm in what McDonnell describes as an exceptional standard for worker housing.

In conversations with both McDonnell and Boot I asked about the general economic well-being of coffee farmers today: With more models for fair and direct trade than ever, and an increasing consumer demand for supply chain transparency, is your average coffee farmer better off than 20 years ago?

“I think our peer group is buying good coffee and paying good prices. But we’re still a smaller segment of the market; coffee is generally a commodity,” said McDonnell. “The reality is that most people who pick coffee don’t have enough resources.”

Coffee is still largely produced by farmers with limited means and infrastructure who are at the mercy of middlemen, exporters and a market that, as it fluctuates, puts pressure on them to lower prices. Equator Coffee & Teas, like many of their Bay Area–based peers, is striving to operate differently. They were the first roaster to become a Certified B-Corp, and have micro-loan and grant programs in regions where they source and grow their beans. But their program at Finca Sophia isn’t scalable enough for as broad of an impact as they would like, and the farmers still don’t own their own land.

Building on his three Good Food awards, Boot says his next step is to focus on launching a consumer brand that provides a unique platform, with a wine-tasting-like experience, for these kinds of specialty coffees.

“The greatest challenge is to be able to have a model where ultimately the farmer can share in the wealth. This cup of coffee can be sold for $15 per cup. We need to make sure that value is getting back to the people at the base,” he said.

“We should be doing that, obviously, because it’s the right thing to do. But the reality is, if we’re not able to do that, people will give up on growing coffee and coffee will cease to exist,” he said. And with that, I slid over my cup and he poured me a little more.