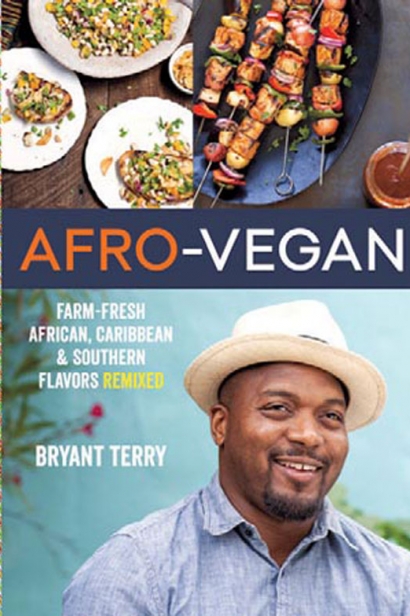

Bryant Terry, Builder of Bridges to Two Misunderstood Cuisines

How many black men from Memphis, Tennessee, are making a name for themselves in the food movement in the Bay Area and beyond by cooking vegan dishes through the lens of the African diaspora?

Just one comes immediately to mind.

No matter. Bryant Terry is up for the challenge. Comfortable with his own convictions, he isn’t fazed by the controversies that abound when Southern soul food or vegan diets are the topic of conversation. In fact, he goes out of his way to address misperceptions around both much-maligned cuisines.

Case in point: His April soiree launching his new cookbook, Afro-Vegan: Farm-Fresh African, Caribbean, and Southern Flavors Remixed (Ten Speed Press, 2014), a standingroom-only, largely African American crowd, at Impact Hub in Oakland, a new co-working space with a political activist bent.

Terry clearly knows how to create community, to use a tired term. But it’s true: The turnout for the event, which was more a celebration among the food justice movement set than it was a traditional book launch bash, was a reminder that it does indeed take a village to raise awareness, bring about change, and throw one heck of a happening party.

The event combined a trio of elements close to Terry’s heart: healthy food, cool tunes and plenty of room to explore racial, political and social justice matters.

Back to that book. Terry is intent on doing his part to showcase African Americans’ rightful place in any discussion of this country’s culinary roots.

“For far too long our food has been marginalized and vilified,” the 40-year-old told the adoring throng. “I really wanted to bring the flavor profiles, ingredients, cooking techniques and past traditions of the African diaspora into wider circulation and people’s consciousness,” he says, describing the motivation behind his latest book. “I want people to know that when we talk about farm and table, garden and table, people of African descent are the originators of that. I think that needs to be recognized.”

A previous cookbook, Vegan Soul Kitchen (Da Capo Press, 2009), was Terry’s way of reclaiming African American soul food, which has earned a bad rep as fatty, fried and full of sugar, a killer in the black community. From Terry’s point of view, African American food is more than belly-busting mac ‘n’ cheese or heart-attack-inducing fried chicken. He grew up in a family where nutritious, homegrown grub such as dark leafy greens, legumes and beans were staples on the dinner table. And bonus: These foods are economical, as well as wholesome, choices.

He’s got a double-whammy dilemma to deal with in this work, since many roll their eyes at the idea of vegan cuisine, which has been dubbed boring, bland, un-fun food in certain circles. Terry uses spice and heat, unique flavor pairings, and techniques such as slow cooking, grilling and roasting to bring vibrancy to the vegan playbook.

Afro-Vegan doesn’t shy away from addressing tough topics such as health disparities, lack of access to fresh and healthy foods and the importance of returning to the kitchen. He also tackles head-on preventable diet-related illnesses that disproportionately affect African Americans, including heart disease, hypertension and Type 2 diabetes.

“For solutions to the health problems that our community faces, we need look no further than our own heritage,” he maintains.

And in a fresh twist, he suggests pairings alongside each recipe—not of alcohol, but music, films and books. So Berbere-Spiced Black-Eyed Pea Sliders are teamed with celebrity chef Marcus Samuelsson’s memoir Yes, Chef, while Creamy Coconut-Cashew Soup with Okra, Corn and Tomatoes is combined with the samba tune “Novo Dia” by Balanca Povo, and Muscovado-Roasted Plantains are accompanied by Jose Feliciano’s Latin soul cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Golden Lady.” Savory Grits with Slow-Cooked Collard Greens share the page with the beat-centric Oh No’s “The Funk.” Tofu Curry with Mustard Greens is coupled with the sounds of Thelonious Monk, and Sweet Plantains and Fresh Corn Cakes are paired with Ghanaian blues.

Music, it turns out, is in the man’s blood.

“My aunt was a well-know soul singer in the ‘70s, my uncle was a house songwriter for Hi Records—that was Al Green’s label,” he explains. “Music was such a part of our family, whenever we gathered we’d cook and we’d play music. The two together just make sense to me.”

That’s not all.

“I want people to enjoy the sensual pleasure of eating good food, but there’s a political mission here as well. My guiding mantra is start with the visceral, move to the cerebral and end at the political. Food is something that everyone can connect with, regardless of race, class, education or geography. It brings everyone to the table,” says Terry, an adage few would argue against.

“When you have people’s attention, that’s when you can start helping them think about how they can make a difference, first as consumers, then as community members and finally as citizens advocating for changes to our policies around food.”

Terry’s focus on food began at a young age. He grew up urban in Memphis, but his extended clan owned small family farms in rural Mississippi. He delighted in spending time there in the summers, out in nature, interacting with animals, swimming in the pond.

“My grandparents lived in Memphis, but they came from Mississippi and deeply understood the importance of growing their own food,” he says. “They had backyard gardens, got food directly from farmers’ trucks when they came to the city and made food from scratch.”

He helped tend the family produce plot.

“It wasn’t always fun; it was chores like planting and harvesting,” he concedes. “They grew collards, turnips, dandelion, mustards, squashes, corn, tomatoes and green beans. My maternal grandmother practically had an orchard in her backyard—pears, plums, peaches and nectarines. It was great. And I have vivid memories of being in the garden with my paternal grandfather.”

His introduction to Southern cooking as a child defies today’s stereotypes.

“We ate a lot of greens—they were ubiquitous at family gatherings,” he says. “It’s one of the things that I’m so clear about when framing my own food, it’s not some newfangled way of making Southern cooking healthy. This is the type of food we ate, and we didn’t necessarily drown it in butter or have it drenched in bacon fat.” Instead, he ate lots of whole beans and black-eyed peas, simply prepared.

In his own recipes, he’s not trying to convert people to veganism, he says, he just wants to offer people—omnivores, carnivores and herbivores alike—options for healthy eating.

“The way my publisher frames my cookbooks for marketing purposes it’s vegan food, but, if it was up to me, I wouldn’t necessarily frame it that way,” he admits. “It’s just farm-fresh, good, clean food. I think those labels often trip people up or push people away. And my work is about widening the net as much as possible and bringing people in.”

While Terry was raised an omnivore, meat wasn’t prominently featured on the plate. It was an economic thing, he says. His parents grew up working class; they couldn’t afford to have big hunks of meat at every meal. Meat was present, but there was attention to just how much was served.

He doesn’t mean to downplay elements of Southern-style fare or pretend he didn’t eat it either.

“I don’t deny that side. On holidays we might have deep-fried fatty meats and red velvet cake,” he acknowledges, “but my focus is on the foods we ate on a regular basis, and we didn’t eat that stuff on a regular basis.”

He started experimenting with vegetarianism in high school; hearing the song “Beef “ by hip-hop group Boogie Down Productions, which rapped about the atrocity of factory-farmed animals, was an early influence. Then health, environmental and economic factors lead him to embrace a more plant-centered diet.

After graduating from Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans, Terry headed to New York University (NYU). He planned on getting a PhD and becoming a professor. Instead, he immersed himself in both the activist and art scene in the Big Apple. He and his roommate were known as the two guys from New Orleans who had fun parties with good food. Terry did the cooking.

Good times notwithstanding, Terry earned a master’s degree in history from NYU.

He also spent a good deal of time exploring the intersection of poverty, malnutrition and institutional racism. He says he was blown away by the brilliance of the Black Panthers, who, back in their day, implemented free grocery giveaways and school breakfast programs in Oakland. In 2002, determined to combine his love of good food with his growing activism, Terry signed up for culinary school at the Natural Gourmet Institute, a program that, while deeply rooted in macrobiotics and vegetarianism, also has instructors with traditional French culinary training. Terry says he had no desire to be a restaurant chef; he wanted to found a nonprofit cooking program for young people, which he did.

Terry spent nine years in New York, but after a chance encounter with Bay Area food activist Brahm Ahmadi, who brought Terry here to teach a class in a Collards and Commerce program, he made the move west at the end of 2005.

“I saw the Bay Area as the epicenter of the food justice movement. Once I landed here, I never left. It’s the right fit for me,” says Terry, who lives with his wife, organizer and community builder Jidan Koon, and their children (baby number two was on the way at press time), in a cute bungalow in Oakland’s culturally diverse Laurel neighborhood. Naturally, they grow some of their own greens.

Terry will take his book tour to the South, of course, and he’ll make sure to get his message across while talking about recipes designed to whet folks’ appetites.

“We’re all caught up in this industrial food system where people are cooking less and eating out more. The most important way to bring people back to the kitchen is by talking about flavor,” he says. “You can talk about politics, health and the environment, but if it doesn’t taste good, people don’t want to eat it. I wouldn’t want to eat it either. Flavor comes first.”

Sing it, Bryant.

STRAWBERRY-WATERMELON SALAD WITH BASIL-CAYENNE SYRUP

Yield: 4 to 6 servings

SOUNDTRACK: “I’m Happy” by Osunlade from Pyrography

BOOK: Songs in the Key of My Life: A Memoir by Ferentz Lafargue

INGREDIENTS FOR STRAWBERRY-WATERMELON SALAD

4 cups strawberries

6 ounces watermelon flesh

1/4 cup packed minced fresh basil

2 tablespoons Basil-Cayenne Syrup (see below)

2 tablespoons freshly squeezed lime juice

1/8 teaspoon Basil Salt (see below), or to taste

TO PREPARE

Quarter the strawberries lengthwise and put them in a large bowl. Seed the watermelon and cut it into small wedges about the size of the strawberry slices and add to the bowl with the strawberries. Add the basil and 2 tablespoons of the syrup and stir gently to combine. Taste and add more syrup if desired. Cover and refrigerate until chilled, at least 1 hour.

Just before serving, remove the salad from the refrigerator and drizzle with the lime juice. Toss gently to combine. Sprinkle with the Basil Salt and serve immediately.

SOUNDTRACK: “Wild” by J Dilla from Ruff Draft (2007 Reissue)

INGREDIENTS FOR BASIL-CAYENNE SYRUP Yield: 1 cup

1 cup raw cane sugar

1/2 cup water

1 teaspoon cayenne pepper

1/4 cup packed minced fresh basil

TO PREPARE

Combine the sugar and the water in a small saucepan over low heat. Stir well. Heat until hot to the touch and the sugar is completely dissolved, about 3 minutes. Add the cayenne pepper and basil and bring the mixture to a boil. Remove from the heat and let steep for 8 hours or overnight. Strain through a fine-mesh sieve into a glass jar and refrigerate until ready to use. (Compost the basil.)

SOUNDTRACK: “Salty Dog” by Jelly Roll Morton from Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings

INGREDIENTS FOR BASIL SALT

Yield: about 1/2 cup

1/4 cup coarse sea salt

1/4 cup packed minced fresh basil

TO PREPARE

Preheat oven to 175°F. Line a small, rimmed baking sheet with parchment paper.

Combine the salt and basil in a spice grinder and process until finely ground. Spread the mixture on the lined baking sheet and bake for 15 minutes, stirring occasionally. Turn off the oven and leave the mixture in the oven to dry for 30 minutes.

Remove from the oven and let cool. Transfer to a jar and seal tightly. Stored at room temperature, it will keep for 6 months.

Recipes reprinted with permission from Afro-Vegan by Bryant Terry, copyright © 2014. Published by Ten Speed Press, a division of Random House, Inc.