Petaluma, Land of Eggs & Butter

There were egg queens and chicken dances. A 15-foot egg basket at the railroad station and a 400-member chorus on stage. The order of Cluck Clucks. A national egg laying contest. A professional chicken impersonator.

Above the corner of Third and Market Streets in San Francisco, two sacks of chicken feathers were released from a plane, floating lazily through the air as they fell to the ground. Attached to each feather was a small card granting the bearer three dozen of Petaluma’s finest eggs.

It was 1922, Petaluma was the egg basket of the world and Egg Day was the day to crow about it.

These days, the floats at the Petaluma Butter and Eggs Day parade and celebration are a bit flashier, the food is undoubtedly more varied, and the giveaways come weighed down with a little more plastic. The annual tradition, spanning several blocks with kid-friendly activities, contests and vendors, typically draws almost 30,000 people and includes over 3,000 participants.

When I was asked to write about the celebration, I have to admit that I met the opportunity with some hesitancy. My experience with county fairs and parades extended to shielding my eyes from the naked people at the “How Berkeley Can You Be?” parade and a distant memory of looking up at a giant horse, supposedly the world’s largest, at a county fair in the Gold Country.

How many words could I write about a local parade? Turns out, many—and they weave back past the corn dogs and tractors into a time when eggs and chickens put a small town on the world map.

The first parade, as I learned at the Petaluma Historical Library and Museum, took place on April 1, 1916. It is tempting to imagine that the annual 100-unit parade has been sauntering down Petaluma Boulevard for almost a century. But in 1926, there was an abrupt stop in the timeline: The parade tradition was broken, and it wasn’t until the 1980s that it was re-inaugurated as Butter and Eggs Day.

The story of the rise and fall of Egg Day, and then its revival six decades later, is a captivating one. It’s a story of inventors, of the drive of immigrant families, of over-the-top entrepreneurial spirit and it’s a story of farming in America. It begins, like so many stories do, with a group of men hoping to get rich.

EGGS

The men who came for the gold rush didn’t find gold in Petaluma, but they found a temperate climate, rich soil, a river that flowed into the San Francisco Bay, and plenty of land. Turns out, Petaluma was a perfect environment for raising crops, and especially well suited for chickens, peculiar creatures that freeze easily in the cold and don’t take well to heat. From the 1850s to the 1870s, families began to raise backyard chickens, mostly for themselves and to make a small living supplying San Francisco’s population boom. Typically a hen broods on her eggs for three weeks until they’re ready to hatch. The production cycle for family farms—with the hen as a bottleneck—was somewhat challenging to bring eggs to market quickly. It wasn’t until two men met over a toothache that things started to change.

Historians are not sure who did most of the inventing, but when dentist Isaac Dias and Canadian medical student and chicken rancher Lyman Byce met, they had both been tinkering with the idea of a chicken incubator: a device that would separate the eggs from the hen, keeping the eggs at the right temperature for them to hatch and subsequently freeing the hen to keep producing. Their joint creation was first introduced in 1879 at a California state fair (Byce dazzled the crowd by incubating reptile and ostrich eggs, as well as chicken eggs).

Thus, the Petaluma Incubator Co. was born, laying the first brick in Petaluma’s chicken farming infrastructure. Byce began shipping incubators across the country, stock and dairy ranchers switched to poultry, and real estate ads listed the number of acres, bedrooms and White Leghorn hens.

“Now the Petaluma River was getting a lot more attention, eggs were being shipped down it to San Francisco, hatcheries were developed, poultry farms were developed, chicks were sent down the river, and all of this was centered on Petaluma,” said John Benanti, a historian at the Petaluma Historical Library and Museum. “By the late 1800s, Petaluma was a booming little center of poultry.”

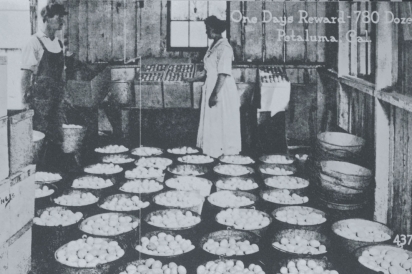

At its high point, Petaluma boasted several large-scale chicken ranches, multiple firms dedicated just to the purchase and shipment of poultry, multiple hatcheries and at least 1,000 chicken farms. The chicken business extended from small family farms of two acres to 40-acre poultry ranches producing 300 cases of eggs per day. At one point, nine out of 10 families in Petaluma were raising chickens. The city of about 6,000 people was now the nation’s leading egg producer.

Around that same time, across the world in Greece, Bert Kerrigan was competing to be the best high jumper in the world. The 1906 American Olympics team faced rough seas on the journey over and Kerrigan, a 27-year-old Portland native and the Pacific Northwest high jump champion, was injured aboard ship, leaving him tied for the bronze medal (a major blow to his budding career). As high jumping was out of the picture, Kerrigan returned home to pursue a career in public relations. Ironically, his timing was good—the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce needed help rebuilding business after the 1906 earthquake.

While the rest of the Bay Area was recovering from the devastation, most of Petaluma was left standing, and the Petaluma Chamber of Commerce was tackling a different issue: how to capitalize on new 20th-century technology in transportation and refrigeration, and stimulate Petaluma egg consumption around the world. They recruited one of San Francisco’s most enthusiastic business promoters to help. His name was Bert Kerrigan.

It started with the slogan. “Petaluma, the World’s Egg Basket” was soon stamped on the cover of brochures beckoning families to come to Petaluma and pursue their dreams of prosperity—all they needed was a plot of land, the right tools and a few flocks of chickens.

The pinnacle of Kerrigan’s campaign was the parade, an event that got more elaborate (and increasingly quirky) as the years went on. By the 1921 parade, film crews had made newsreels of the Must Hatch hatchery, Petaluma chickens were dominating a national egg laying contest, celebrities were invited to the Egg Day Ball, and California’s governor had graced the parade stage. At one point, 7,500 eggs were barbecued and handed out to parade guests. In 1922, the Egg Queen contest went national and “her highness” was flown in from Tennessee.

Along with the showmanship, Petaluma’s economy grew. In 1920, almost 3 million poultry were shipped out of Petaluma. By 1922, the figure grew to 12 million poultry and 27 million dozen eggs. The Hotel Petaluma was built specifically for affluent parade guests. Other industries—for instance, a formerly shuttered shoe factory reopened, creating 100 jobs—began flocking to the area.

Kerrigan’s influence on the egg industry spread nationally. For years, imported frozen Chinese eggs had been gaining market share in the commercial baking industry. Domestic producers were concerned, and not without cause. In 1920 Chinese poultry imports were worth $16.3 million. Kerrigan traveled to Washington, D.C., and lobbied for an embargo on imported poultry products. On Egg Day of 1922 Congress passed the first tariff establishing import duties on foreign dried and frozen eggs.

Not surprisingly, the Petaluma Chamber of Commerce was broke by 1924, dried up largely by Kerrigan’s flamboyant and costly campaigns. The Chamber and Kerrigan parted ways and it wasn’t long before the economic downturn blew in and parades were an extravagant thing of the past. Kerrigan stayed in Petaluma for a few years before moving to Menlo Park to work for the California Public Utilities Commission.

Until the late 1950s, though, Petaluma still had an egg business, mostly comprised of small family farms. But when the familiar chorus of industrial woes hit Petaluma—big agribusinesses grabbing ahold of the industry, some moving production to more affordable areas in Southern California—it was no longer a feasible living for most families.

It wasn’t until the 1980s then that the idea of bringing back an Egg Day parade emerged, this time with butter in the mix. “The Petaluma Chamber of Commerce and the Downtown Association decided to bring back a parade. By then the poultry industry had declined, but butter and cream had risen to the top of the agricultural industry,” explained Marie McCusker executive director of the Downtown Petaluma Association. Save for the grape and wine industry, dairy is still on top.

BUTTER

Frank Gambonini loves his old milk tank, a rusty, silver obsolete tank with “Milk, It Does a Body Good” and a faded blonde model plastered on it. It sits in the driveway across from his family home, just past the calves in their pens, next to the stables that hold his 250 cows. He tells me with a bashful smile that his wife wants him to get rid of it. He takes me to the top of his ranch, several acres passed down from his great-grandfather that roam up from Lakeville Highway and look out all the way to the San Francisco Bay on a clear day.

“We’re fourth generation dairymen here in Petaluma, and fifth generation in California,” he said. “We just celebrated our 100th anniversary on this land.”

Silvio Gambonini, Frank Gambonini’s great-grandfather, began dairying in 1913. Like other Southern European immigrants, the Gamboninis came to the North Bay to tend and milk cows as they had done in their homelands.

“Dairyman used to put milk in cans on the river and float it down to San Francisco,” said Gambonini. “The cooperative was founded on the idea of coming together to line up all this haul and get a good price for our milk.”

Silvio Gambonini was one of the 35 founding members of the Petaluma Cooperative Creamery, a dairy plant established in 1914 that would fulfill San Francisco’s increasing need for butter, and create a steady market for the small family farms selling cream and milk. Butter was their first product, and it was there that the Clover brand name was born, along with multiple other product lines.

“The cooperative started growing over time and just got bigger and bigger,” said Gambonini. By the 1960s and into the 1980s, Sonoma and Marin counties made up one of the top-producing dairy areas in California.

“In the 1960s there were 150 dairies in Marin County, now there are 25,” said Albert Straus, president of Straus Family Creamery. Straus represents the new face of Petaluma’s dairy industry—perhaps smaller in numbers than in its heyday, but more sustainable and organic. He is the oldest son of Bill and Ellen Straus, who began their family dairy farm in the 1940s. By the time Albert Straus reached adulthood, the dairy industry had changed: Small family farms were being replaced by large dairies that were altering the price structure for the industry, making prices unrealistically low for family farmers.

By the early 1990s, organic stickers on fruits and vegetables were popping up in markets around the country, but milk was stuck under the control of large processors and regional cooperatives, and had no organic options. When Straus converted the family farm to organic in 1993—the first certified organic dairy in California and west of the Mississippi River—he had no one to sell milk to, and intended to create his own retail label. In 1994, the Straus Family Creamery was born, allowing Straus to craft organic milk and cream products to his own liking, and providing a new marketplace (and business model) for family dairy farms.

“Considering the state of the economy and the dairy industry, I’m not sure if we could have continued if we hadn’t made the switch to organic,” said Gambonini, who converted his dairy to organic in 2007 and sells to organic processors. “In the conventional industry the price system is dynamic, but with the organic system we can line up contracts with the buyers, and we know we’ll have a fairly stable price, which makes running a business much easier.”

Conventional dairies in Marin and Sonoma are now the exception: the McClelland’s Dairy, with roots going back to the 1930s, has made their own artisan organic European-style butter since 2009, and Clover Stornetta, one of Petaluma’s largest employers, has offered organic certified products since 2000. Straus tells me that 75% of dairies in Marin and Sonoma counties are now organic. His creamery works with eight family farms in the area and is currently looking for more.

“We’ve made a model that supports the family farm, allows them to sustain profit and make a sustainable farming system,” he said. “Organic is a vital element to revitalizing farming communities.”

It’s become clear that a product like Straus European-Style Organic Butter—created at the suggestion of Alice Waters 20 years ago and now a favorite among chefs for its high fat content—represents the alignment of elements that make up a healthy food ecosystem: when what tastes the best is the best for the environment, the consumer and local producers.

“We are who we are because of where we are,” said Joanie Benedetti Claussen, director of marketing at Clover Stornetta Farms. “We have amazing local dairy families here in Petaluma and the surrounding areas, we have so many different independent grocery stores in California, and by virtue of being in the Bay Area we have a consumer base who understands that you have to pay for good food and that supporting local is just something you do.”

THE JEWISH CHICKEN FARMERS OF PETALUMA

What they had in common was language. Readings from Yiddish writers, Jewish folk chorus and Yiddish drama group. Self sufficiency: growing vegetables and raising livestock—so abundantly that a visit into town was only necessary for sugar and flour. An “otherness” in a small town with few ethnic minorities. A steadfast connection to the currents of international politics, deep socialist ideals and a draw to a life living off the land. For the first decades of the 20th century, Eastern European Jews came to Petaluma, getting in on the chicken businesses and building a community with a unique historical legacy.

“They came because they heard you could own land and be your own boss, which in Russia they couldn’t do,” said Bonnie Burt, director of A Home on the Range, a documentary on the history of the Jewish chicken ranchers in Petaluma. In Czarist Russia, Jews were prohibited from owning land, prompting a movement of Jewish agricultural settlements in Palestine and elsewhere, but rarely in the United States.

Sylvia Schwartz grew up on the 10-acre farm her father and uncle bought four miles outside of town when they arrived from Russia in 1915. By the 1920s, a few hundred families like the Schwartzes had grown into a vibrant community, and even the sweatshops in New York were humming with rumors of socialist Jewish chicken farmers out west.

The Petaluma community was a hub for Jewish culture and leftist politics: an International Workmen’s Circle was held regularly, community members supported and organized labor strikes, and visiting Jewish intellectuals and poets put Petaluma on the New York to Los Angeles circuit. While the early settlers were mostly non-religious, casual socialists, with coming generations the community began to split into factions of Communist Party members, casual socialists and Zionists. Tensions heightened in the McCarthy era, and the Jewish Community Center, once the central gathering place for all families and activities, became a battle zone with some groups eventually being prohibited to enter.

Many of the sons and daughters of the founding generation stayed in Petaluma, taking over their parents’ chicken ranches or building their own. Schwartz moved to her own farm when she got married and raised meat birds, selling to a local co-op. She lived there with her children until the late 1950s, when the local chicken industry met its decline and most families moved to urban areas.

“No one became wealthy doing this. But all our young friends were in the same situation, there were fewer than 100 families and we all knew each other,” said Schwartz. “I’m always reminded of Hillary’s ‘it takes a village’ saying. We really did all take care of each other; these were our kids.”

THE NEW CHICKEN FARMER

Just as the organic market sparked a comeback for local dairy producers, so it has for egg producers.

“I don’t have anything against industrial farms, I just do it my way,” said Don Gilardi as we walked past the orange and white chickens clucking around his 80-acre farm. I learn that this casual type of response to my somewhat persistent questions about the challenges of modern-day chicken farming is typical of Gilardi. Straight to the point, like what he’s doing is no big deal.

“We just try to produce the best product out there,” he said, shrugging his shoulders.

But it is a big deal. First off, when Gilardi’s mother passed the farm on to him, he was in real estate, without the ambition or expertise to raise sheep, which had been her focus. (“I was, like, ‘I don’t want sheep!’” he said.) He began raising chickens, building and tearing down coops through trial and error. Red Hill Farms’ pasture-raised organic rainbow chicken eggs are now sold at Whole Foods Markets, Bi-Rite Market and other grocery stores throughout the Bay Area and as far south as Santa Cruz. Gilardi himself has 3,000 to 4,000 chickens and works with nine other farms in Sonoma and Marin counties that raise and produce eggs for him, to the same standards as his farm. His goal is to work with more farmers.

Secondly, the eggs come in different shades of white, brown and green, with deep yellow yolks like daffodils—and they’re delicious. It’s the combination of pure sunlight, open air and a natural diet of pasture and organic grains. The shades change with the seasons and the chickens’ forage.

When I arrived at the farm, Tyler Tuck, Gilardi’s 21-year-old nephew, was scooping newly arrived chicks from a UPS box into their coop. I delicately patted the top of one’s head as he handled them as casually as I handle my laundry going into the dryer. Tuck, tall with short blond hair and wearing a camoufl age jacket, will be taking the farm over soon, making him the fifth generation to work on this land. The farm sits in a valley, below golden hills and dark oak trees with sprawling branches in every direction. Rows of three and four white chicken houses pierce the landscape. At 9am, the light filtered around everything and I (half-ironically) stopped to admire how beautifully it glowed around a pile of dirt.

We are who we are because of where we are. That’s the story of a county fair, or a butter and eggs parade. Tuck has three friends his age who will also be stepping up soon to run their family farms. I asked him if he’s excited about his new role.

“Well, it’s what I’ve been doing forever,” he said as he picked up a chicken and cradled it. “I’ve been opening and closing gates since I could walk.”

The 33rd Annual Petaluma Butter and Eggs Day Parade and Celebration will take place on Saturday, April 26, from 10am to 5pm.