Beautiful Food of Our Children: Re-Inventing Public School Lunches

It is early fall and our six million California public school students are back to school. The lunch bell rings and the students line up in the cafeteria, talking and joking, moving through the lunch line on autopilot. They pay little attention to the everyday offerings—pizza, French fries, mac ’n’ cheese—as they hold out their plates to the servers. They fill their trays, wander off to find a spot at a table and gobble down the meal that has been served to them.

Wait! Stop. Rewind. Let’s try that again. We’ll try something different this time. Let’s re-imagine the typical California public school lunchtime scene. We ring the bell and the students file into the cafeteria line again. There they are, catching up and joking, per usual, just another day at school. But now, as they move through the line toward the servers, they actually turn their attention to the glass cases, which are now topped with bouquets of freshly gathered seasonal flowers, straight from local growers. Inside the cases are beautifully garnished, oversized platters of food, like you might see in a classic film about a family in the Italian countryside, or maybe on the table at a Mexican feast.

A whole-wheat penne pasta salad with tuna and capers has been sprinkled with fresh basil and shaved Parmesan. Sliced lime and cilantro leaves adorn a colorful cucumber and jicama salad. The soup of the day is albondigas, a traditional Mexican soup, chock full of rice and homemade meatballs. Rising steam carries the aromas of oregano, mint and cilantro.

The students begin to notice the day’s offerings, mentioning how hungry they are as they get closer to the front of the line. Handwritten signs and photographs describe the farms that have provided the ingredients for today’s lunch. And, finally, we turn our attention to the food service employees, the people who have created these delicious offerings, who are eager to explain to the students the names, flavor profiles and health benefits of the dishes. The students now pay full attention to the food, to the enticing smells and sights, as they make their choices and carry their trays to tables. While we’re at it, we will drape those cafeteria tables with checkered tablecloths and more small bouquets of fresh flowers, and we’ll imagine that the children linger at the table, talking while they enjoy their meals.

In California, 900 million school lunches are served each year. That makes 900 million opportunities fornyoung people to develop a positive relationship with fresh, delicious and healthy food, 900 million chances to teach young people that paying attention to what they put in their bodies, to the choices they make at meal time, and even how often they take time to enjoy a meal, matters immensely to the overall quality of their lives.

Why not reinvent the school lunch? Would it be so difficult? Zenobia Barlow at the Center for Ecoliteracy in Berkeley thinks not. She believes a transformation is afoot, and very much within reach. Barlow is at the helm of a public education initiative entitled Rethinking School Lunch.

This program, described in the Center for Ecoliteracy’s literature as a “planning framework for redesigning school food systems,” has been 10 years in the making and addresses 10 aspects of school operations that are critical to improving the way our children eat—everything from procurement and dining experience to facilities and finance.

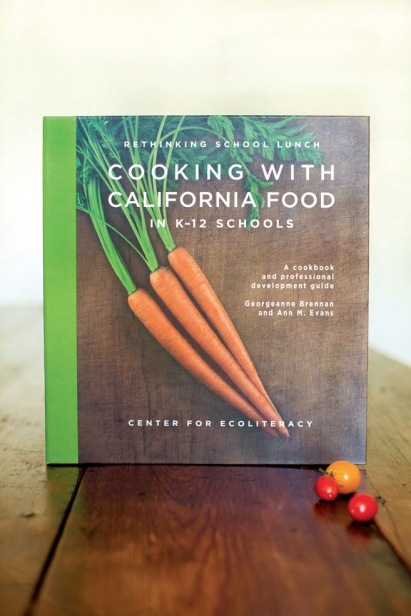

Most recently, with the publication of a cookbook and guide entitled Cooking With California Food in K–12 Schools, and the offering of hands-on classes based on the cookbook (funded by both the Center for Ecoliteracy and the TomKat Charitable Trust), the focus of this initiative has moved to a previously overlooked aspect of school lunch reform: professional development for food service staff.

“Food is beautiful and, in California, agriculture is abundant. We care about and love our children, and our food service employees want to nurture them,” Barlow says matter-of-factly as we discuss the overarching goals of the initiative in her office in the David Brower Center on the edge of the UC Berkeley campus. “If you get to the point where change is feasible, then you need to do it.”

This balance of compelling idealism and brass-tacks realism infuses the equally gorgeous and practical cook- book, which was created specifically for California public school food service employees. Cooking With California Food in K–12 Schools opens with an 1888 sepia-toned map of California, showing cultural landmarks and agricultural areas, followed by a letter from co-creators Georgeanne Brennan (a regular contributor to Edible Marin & Wine Country) and Ann Evans to food service providers: “We invite you to adapt the concepts developed in this book in order to introduce seasonal fruits and vegetables, sourced locally, into dishes that are popular with children and reflect our state’s diverse cultural heritage. As you do, give thanks to the soil, the water, the sun and those who work the land for the confluence that makes such food available to our children.” Notably absent is any offering of thanks to the heat-and-serve chicken nuggets flown in from Chicago they might be used to serving.

In January of this year, First Lady Michelle Obama and USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack announced the first reform of school lunch guidelines in more than 15 years. These much- anticipated new guidelines mean that all subsidized school lunches will come with less sodium, more whole grains and a significant increase in sides of fruits and vegetables. At a historical moment when the incidence of obesity has hit 34% of the population and health care costs related to this epidemic were estimated at an astounding $190 billion last year, no one denies that we are in the middle of a legitimate American health crisis.

While the recent mandated changes are a welcome step, in reality lobbies for the companies that profit from the archaic school lunch system (large-scale potato growers and frozen- food providers, to name two) have the ear of the anti-big- government element in Congress and, often citing the prevention of legislative overreach as their reason, prevent the necessary radical overhaul of our school lunch procurement and nutrition guidelines. We live in a strange time when adult desire for profit is in a deadlock against the nutritional needs of our youth. With the introduction of Cooking With California Food in K–12 Schools, Barlow, Brennan and Evans, along with many local food service directors, are coming at the issue with a refreshing new approach.

“People involved with food service in the schools are very dedicated and passionate people,” says Brennan, who uses the cookbook as a guide when teaching cooking classes to food service employees in the public school districts

as part of the Rethinking School Lunch initiative. “As servers, they are often labeled the ‘bad guys,’ but they are a huge resource, and our challenge is to acknowledge them as a resource. They are people who cook at home. They are from diverse ethnic backgrounds, and they want to nourish our students.”

Last year, San Rafael City Schools’ Director of Food Services Elena Dribble and Novato Union School District’s Director of Food and Nutritional Services Miguel Villareal attended a Cooking With California Food introductory course for food service directors and kitchen managers taught by Brennan and Evans in Davis. Dribble and Villareal were very impressed by the course, and had been waiting for an opportunity to bring professional development to their schools. They returned to Marin, worked to secure the needed funds and, this past July, food service employees from the two districts gathered in the San Rafael Cooking School in Terra Linda to explore the basic concepts and recipes in Cooking With California Food.

“Participants arrive, we go over ingredients that are seasonal or unusual. Then I introduce spices and herbs that are part of the flavor profile we will use in our recipes, and they team up into groups of two or three,” says Brennan. “At first it is controlled chaos. It is roaring in the kitchen. Then it gets quiet, and beautiful, garnished dishes begin to appear. A member from each team introduces their dish. My goal is to eliminate the ‘false wall’ between home food and school food, adult food and kid food.”

Brennan, an award-winning cookbook author, food writer and cooking instructor, earns rave reviews for the tenor of her classes. “Georgeanne is brilliant,” says Barlow, who has witnessed Brennan working her culinary magic, primarily with food service workers in the Oakland school district. “I have seen food service staff arrive at the class but leave their jackets on and keep their purses over their arms. They are suspect for the first 10 minutes, but she is respectful and sensitive, an expert who is able to get people engaged as quickly as possible.”

Having taken the course herself, Elena Dribble concurs: “This is a class for my employees who are in the trenches with the kids,” she says. “Georgeanne is not patronizing, which is refreshing. She recognizes that this is about the staff and the work they do. They need to be recognized and honored.”

Lest we assume the Rethinking School Lunch initiative tosses the baby out with the bathwater—ignoring the tried, true and surprisingly universal taste preferences of the diverse California student body—it is important to note the underlying framework for the cookbook. The outline for the recipes is a “6-5-4 School Lunch Matrix,” based on six dishes that students “know and love,” five ethnic flavor profiles and four growing seasons. In other words, students will be eating freshly cooked and locally sourced salads, soups, pastas, rice bowls, wraps and pizzas with flavor profiles representing Africa, Asia, Europe/Mediterranean, Latin America and the Middle East/India. Over the course of four seasons, the recipes integrate various herbs, spices, grains and seasonal produce brought to California by immi- grants over the past 200 years, now integrated into our 21st century cuisine.

With an understanding that most regional public schools range from large to very large in size, these recipes are also designed for scalability. At the San Rafael school district, for example, Dribble is feeding 2,500 students each day, and at this point she predicts that she will be able to introduce 16 of the cookbook’s recipes this fall.

With more progressive guidelines coming out of Washington, the support of regional entities such as the Center for Ecoliteracy and extraordinary access to regional agriculture, Bay Area school lunch programs are poised to become national models. Ultimate success will depend largely upon each district’s internal will to transform their programs.

In its introduction, the cookbook acknowledges that certain nuances, such as the definition of the term “local,” will lie in the hands of the district administrators. “‘Local’ refers here to the state of California,” the introduction explains. “However, school districts use a variety of definitions. For example, local might be defined as the foods coming from within a 100- or a 300-mile radius.” Clearly both options are an improvement over the cross-country frozen imports that were the rule in school kitchens of our recent past.

In Novato, Villareal has worked for the past decade to connect his cafeterias and his employees to the extremely local producers in his Marin County backyard. “I take my staff out to the nearby farms to get a sense of where this food is coming from. I want each of them to understand that they are making a difference, that they are much more than just ‘the cafeteria lady.’ I call my employees ambassadors. This class will engage them even further in the process. They will go to school and PTA meetings and be able to tell parents directly, ‘I am here to make sure your kids are getting the best possible food we can provide.’”

A major roadblock to implementation of nutritional reform is the archaic state of most district cooking facilities—in particular, kitchens designed for “heat-and-serve” rather than storage of and cooking with fresh produce— and a lack of available funds to remodel. Dribble is grateful for the investment the San Rafael school district has made in infrastructure improvement and salad bars over the past five years.

“My district recognizes this change as a part of the students’ education, an important piece. The classes are so specific to exactly what we are trying to do here.” And both Dribble and Villareal believe that even simple improvements bring notable change. “Just having sharp knives and some cutting boards in the kitchen can make all of the difference,” says Villareal. “Our employees need the tools to do this job well.”

While Michelle Obama and others work against the prevail- ing forces in Washington, our local heroes, fortified with cookbooks and clear vision, will go about pursuing the dream of fresh and nutritious school lunches here on the ground in California, one recipe at a time. Asian cabbage and orange salad with ginger; fideo pasta with chorizo and kale; lemon chicken with fresh cilantro...

The Center for Ecoliteracy has made the Cooking With California Food in K-12 Schools cookbook and guide available online and, according to Barlow, it has been downloaded 22,000 times since last August (2,500 of those downloads were the Spanish language version).

If Barlow and others behind the Rethinking School Lunch program are correct, that beautiful re-imagined cafeteria, the place where students learn to connect locally sourced and freshly prepared meals to the health of their bodies and our environment while enjoying meals served by food service “ambassadors,” is not so far off.

To download a free copy of the Rethinking School Lunch Guide and Cooking With California Food in K–12 Schools, and other materials related to school lunch reform, visit Ecoliteracy.org/change.