Surfing Amber Waves of Grain, Part I: The Farmers

“We are challenged by the capacity to do all of this fast enough, the interest is growing so rapidly, this is a pretty big wave we’ve happened upon.”

— Doug Mosel, North Coast grain grower “Bringing Grains Back Home” session at EcoFarm 2012

Furrow by furrow, and fold by fold, The soil is turned on the plain; Better than silver and better than gold Is the surface-mine of the grain… When the stock is swept by the hand of fate, Deep down in his bed of Clay The brave brown Wheat will lie and wait For the resurrection day…

— From the poem “Song of the Wheat” A. B. “Banjo” Paterson, November 1914

Farmer, miller and baker — a trinity that provides strength, sustenance and health to the heart of a local food system. In the late 1880s, California ranked second in the country for wheat production and mills were scattered throughout the state, situated no more than a daylong wagon ride from local grain growers. By the turn of the century, this trinity had drifted apart for a variety of reasons including soil depletion, plummeting wheat prices and the higher profits to be made growing fruits, nuts and vegetables.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 and the invention of refrigerated railcars and other modes of transport had enabled California’s transformation into an irrigated Garden of Eden, providing foodstuffs for the rest of the country, but in that we lost a critical piece necessary for the independence of our own local food economies.

Fast forward some 100-odd years, and the abandoned arts of growing, milling and creating food from local grains are being resurrected through the work of passionate farmers, millers, bakers, restaurateurs, community builders and food security advocates all over our area. In this and following features in Edible Marin & Wine Country we will explore the reasons why this important resurgence is happening and the powerful synergy of the trinity of farmer, miller and baker and its most important product: community.

My own childhood understanding of community was shaped by stories surrounding the small grain mill and general store in rural Mississippi that my grandparents had purchased as a means of riding out the Great Depression. Pappaw said they bought it because people always need a place to grind their grain and get supplies. Mammaw, who taught school, said it was always wise to be in the middle of good farmland and good people. It was not long before no one had cash to spend and the community pulled together to trade with each other for goods and services. At the mill, families in need could sign for goods and pay when they could. I was told that after the mill was sold my grandparents still received checks from people paying off their balances and every debt was eventually paid.

In the spring of 2008, sitting for the last time with my Aunt Gladys on her Southern front porch drinking sweet tea, I reassured her that in my adopted home of West Marin we had Mammaw’s requirements of good people and good farmland in abundance and that this included a steady supply of fresh local eggs, milk and even oysters. Less than completely convinced, she admonished, “Bet you can’t get good stone-ground grits or cornmeal out there.”

Aunt Gladys’ instinct was proven to be correct when the official report from a study titled “Think Globally — Eat Locally: San Francisco Foodshed Assessment” was released later that year (known as the Foodshed Report). The Foodshed Report announced the findings of the study on food production within a 100-mile radius of the city’s iconic Golden Gate that had been jointly conducted by the groups American Farmland Trust, Sustainable Agriculture Education and Agriculture in Metropolitan Regions, a program within the Center for Global Metropolitan Studies at UC Berkeley. The Foodshed Report stated that we could, in fact, feed the population of our own foodshed very well, except that a few commodities were not being produced in enough abundance — including, critically, wheat. (A full copy of the Foodshed Report is available.)

Thankfully, Doug Mosel and a handful of other farmers in the area were already stepping up to the challenge. Doug, who had primarily been farming hay, recalls that the idea of growing grain came to his attention during the “Steps Towards a Local Food Economy” gatherings that took place between 2005 and 2007, primarily in the Anderson Valley, where grain had also been identified as a gap in local food production. What began for Doug as a few plots in the Anderson Valley has blossomed into the cultivation of around 50 acres on the Nelson Family Vineyard property in Ukiah, where he grows grain, as well as rye, barley and oats.

Doug is not the only local grower who is now cultivating grains among the vines. Others include the Freys of Frey Vineyards in Mendocino, Lou Preston of Preston Vineyards in Dry Creek Valley and Peter and Mimi Buckley of Front Porch Farm in Healdsburg.

Is there a natural affinity between vineyards and wheat? If you have a question about what works best with respect to Mother Nature, it seems all roads lead to Lou Preston, who was also an inspiration to me for a story I authored on the restoration of riparian zones in the Dry Creek Valley that appeared in the Fall 2009 issue of Edible Marin & Wine Country. Lou says he initially started growing grains because he’s an avid bread baker and “Grains are a valuable food crop that work easily into a farm crop rotation. When you take out a vineyard block for replanting, the current practice for sustainable growers is to leave the area fallow for a time to allow the land to heal. Wheat works especially well because it can fit into a grape grower’s annual rhythm of winter legume cover crop, followed by a cash crop in the spring and summer.”

Preston has successfully grown hard red wheat; Sonora wheat, a heritage variety historically grown in the region; and rye. He has his own mill onsite, as does Frey Vineyards. The Buckleys and their farm manager, Matt Taylor, the former winemaker and vineyard manager at Araujo Estate, are growing several heritage varieties of wheat specifically for Community Grains, a small but growing producer of wholegrain flours, pastas and polenta started by Bob Klein, the owner of Oakland’s Oliveto restaurant, that is dedicated to fostering the production of local grains (oliveto.com/communitygrains).

Local foodshed advocates and owners of Wild West Ferments, Luke Regalbuto and Maggie Levinger of Marin, have also begun to cultivate their own grain. The reason, they told me, is that they “Want to decentralize food production and show people that it makes sense to grow grain on a small scale, in one’s own backyard, or cooperatively in a community grain field.”

Steve Quirt, recently retired organic and sustainable agriculture coordinator for the University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE), has been a heroic advocate for the resurrection of local, organic heritage grains and has given access to folks like Maggie and Luke to test plots at his Open Hand Farm in Tomales. While at UCCE, Steve supported the College of Marin’s Indian Valley Organic Farm and Garden in trials of growing ancient wheat varieties, as well as additional trials in the Hicks Valley, Bolinas and Tomales areas. He believes that grains should be cultivated locally for human consumption, as well as livestock feed, in recognition of the fact that we can not have a truly independent foodshed if ranchers have to import all of their silage needs.

Other local grain growers include Deborah Walton and her husband, Tim Schaible, of Canvas Ranch in West Petaluma (canvasranch.com). Canvas Ranch started growing Emmer wheat (also known as faro) about two years ago. Emmer was first cultivated in Babylonia around 7000 B.C. and was the dominant crop in the Middle East during Old Testament times. Emmer was later replaced by wheat that was free threshing — meaning the grains can be removed from the husks without pounding or machinery. When Deborah and Tim decided to grow the ancient grain in small but commercially viable quantities, they knew were going to have to have the necessary threshing equipment specially made. Their previous method of putting their Emmer in pillowcases and beating it against the side of the house would not work… This year’s crop will be in by July and available directly from Canvas Ranch’s stall at the Saturday Santa Rosa Farmers’ Market and Sunday Marin Civic Center Farmers’ Market.

John Glavis, a botanist and Permaculturalist who founded the BoTierra Biodiversity Research Center in Bolinas, says that his interest in growing grains locally comes from his concerns about sudden shifts in our food system due to small or large economic collapse, as well as the threats from climate change. In talking to him, it is not hard to tell why he has affectionately been called the “Department of Homegrown Security.” After experimentation with a number of indigenous grains from around the world such as Khorasan Wheat (KamutR) and hull-less barley from Tibet and Nepal that did well, he says that he believes that quinoa is the perfect high-protein grain for growing along the Northern California coast. Quinoa is a “pseudo-cereal,” because it’s not actually a member of the grass family. It’s more closely related to spinach and tumbleweeds. But its stellar qualities of edible leaves with a 20% protein content and seeds with 16% protein content explain why quinoa was a staple for the Incas. John is currently growing 11 varieties of quinoa. What a difference a year makes. In March 2011, Doug Mosel organized a gathering of the growers he knew about who were growing grains in the Northern California coastal area to discuss the state of grain cultivation in the region. The meeting was held in the barn at Nelson Family Vineyard, where they’ve been graciously hosting Doug’s endeavors. About two dozen growers came. This group became the starting “kernel” for what is now called the North Coast Grain Growers Association. This past March they held their second annual meeting in the Nelson barn and more than 50 folks came out, in a heavy spring storm, to share their successes and challenges in growing. This time, local millers and bakers came as well.

The trinity of farmer, miller and baker in Northern California is rapidly coming together again and creating a new community. Look for the story of the next link in the chain of this exciting local wave, the millers, in the Fall 2012 issue of Edible Marin & Wine Country.

MILL MAGIC IN NAPA

Old Bale Mill at the Bale Grist Mill State Historic Park on Mill Creek in Napa is a water-powered grain mill built in 1846, predating California’s statehood. Dr. Edward Turner Bale received the land on which the mill was built in a grant from the Mexican government. While in operation, the mill was a center for social activity in the Upper Valley. Settlers came to the mill to grind local Sonora wheat and corn, two of the Valley’s major crops at the time. According to the mill’s website, the slow turning of the old grindstones and the dampness of the mill’s site gave the meal a special quality for making cornbread, yellow bread, shortening bread and spoon bread. As old timers put it, “When meal comes to you that way, like the heated underside of a settin’ hen, it bakes bread that makes city bread taste like cardboard.” The mill remained in use until the early 1900s.

After many years of neglect, the mill has been recently restored to perfect operating condition. Under the watchful eye of miller Jim Annis, grist (grains like wheat, corn and barley) is again being ground on the renovated original quartzite stones from France — and visitors are invited to watch the entire process. The grounds of the mill are open daily and tours are available on Saturdays and Sundays. It’s a magical moment when miller Annis asks for a volunteer to help him open the sluice gates to activate the big water wheel with its new redwood slats. Jeanne Marioni, outreach coordinator for the Napa Valley State Parks Association that, along with the Napa County Regional Park and Open Space District, helped to renovate and now operate the mill, says that the groups are excited about the new possibilities for more community involvement and education. For more information visit napavalleystateparks.org or call 707.963.2236.

Monica Spiller of the nonprofit Whole Grain Connection (sustainablegrains.org) supplies seeds and advice to most of the grain growers in the Northern California area. Monica has devoted most of the last three decades to the study of and experimentation with the different varieties of wheat that were historically grown in this area.

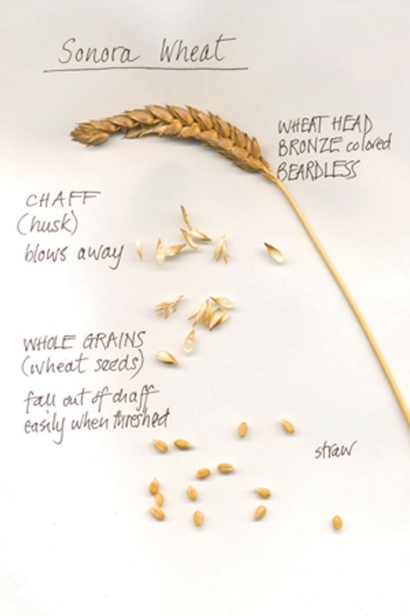

According to her, one of the most popular varieties is the Sonora that is being grown by Lou Preston, among others. This soft white wheat was probably the first wheat introduced on the American continent by the Spanish in the 1500s (although there is some debate about this). It was the variety used by native peoples in Mexico in making their staple of whole-wheat tortillas. Brought north by the Spanish friars for their missions, Sonora was widely planted in California by the early 1800s and up through the Civil War and provided most West Coast residents with their flour during that period.

Sonora is specially suited for small organic farming, as it is naturally tall, and thus able to shade out weeds and reduce the need for herbicides. It is also extremely disease and drought tolerant, capable of producing an abundant crop with no irrigation and less-than-optimum soil as compared to modern wheat varieties.