'Til the Cows Come Home: Marin’s Rich History of Dairying

These days, food-lovers flock to the northern San Francisco Bay Area to sample the best in restaurants and local produce, and to appreciate the fine rural scenery and ambiance. Leading attractions are our prize-winning local cheeses and other fine dairy products. We are seeing a renaissance in dairying, but Marin County is not new to the gourmet market: In fact, it is the pioneer in quality dairy food in the West.

Marin County is such a desirable place today because of its prosperity, good schools, proximity to San Francisco and— most significantly—natural beauty and vast open spaces. This has been the case for over a century. Recent decades of intense planning and activism have helped to preserve Marin’s sense of place, but the foundation of the county’s magic was laid in its earliest days by the plain and hardworking people, mostly immigrants, who worked the land and passed it on, sometimes stubbornly, through the generations.

Agriculture, specifically dairying, has dominated Marin County commerce and economics since the beginning, and still contributes in a major way. By the end of the 19th century, dairy ranches occupied almost every bit of non- wooded open space. Many members of early dairy families evolved into leaders in both business and politics, and their names remain in the modern public conscience: Freitas, Giacomini, Miller, Mendoza and Burbank, to name a few.

Beyond providing pretty rural scenes and local color, it’s good to know that California’s dairy industry, now the nation’s largest, began right here in the North Bay.

The great California Gold Rush made it happen. Until that time, the rich pastures of the Marin Peninsula provided sustenance for rangy longhorn cattle that were tended in the laid-back manner of Mexican Alta California. With the arrival of thousands of gold seekers in 1849 and the years following, the new county to the north of San Francisco acquired significance: providing food to the newcomers in both the cities and the mining camps.

Imagine the Sierra-bound 49er who, soon upon departure from chaotic Yerba Buena in a steamer for the Sacramento River, gazed west at the pastoral and rich lands of Marin. There is no doubt that more than a few passengers thought, “I must return to this place and start a farm.” Some didn’t make it as far as the steamer; many early arrivals forsook the rigors of mining and instead stayed close to port.

Early on, local cattlemen like James Black (Black Mountain) and Lorenzo White (White’s Hill) drove their beef herds to the gold fields, but soon the Sierra foothills were stocked with cattle of their own. In this moribund moment, it took the foresight and intelligence of a woman to inspire an endeavor that would, within years, change history in California.

Clara Steele had settled in Sonoma County in the mid-1850s with her husband and various brothers- and cousins-in-law. Like hundreds of others, the Steeles had tried their hand at mining but were drawn to the verdant North Bay hills. The agricultural economy in the region had yet to gel, and the collective Steeles looked for opportunities. Clara noted the need for fresh dairy products on a visit to the bustling new city of San Francisco; she came home, caught and milked a wild cow, and made a cheese from one of her old family recipes. Returning to the city, she found ready buyers.

Clara was not the first in the area to milk a cow or to make butter or cheese; many people had their own dairy cows, but nobody had yet gone into business to the extent that an industry could be defined.

Much of the imported dairy products of the Gold Rush era literally reeked. The Eastern states were producing the bulk of domestic cheese and butter in the country, and very good stuff it could be. But after a journey on a slow ship, around the Horn—lumps of butter floating in some sort of brine, fine cheeses poorly stored, bad cheeses dishonestly labeled— the results were usually disappointing, if not an outright assault on the senses (or the health)! Clara Steele recognized the need for fresh products and spurred her family members to act before someone else did.

The Steeles traveled southwest into Marin County in search of good grazing land with water and a boat landing. They found it in the wilds of Point Reyes, and signed a lease on the Fourth of July, 1857. The Steeles invested in the creation of a vast, well-run, 10,000-acre dairy ranch on the coast, bathed in fogs that created pasture conditions that they termed “Cow Heaven.” Within years, the Steeles operated three busy dairy ranches and a schooner that made regular deliveries to San Francisco. Their cheese and butter grew in reputation and got top dollar; it put Point Reyes on the map. The Steeles had the first large-scale dairy business in California, and others quickly followed.

As “dairy fever” struck Marin County during the 1850s and 1860s, every available bit of grassland formerly grazed by elk and the Mexican longhorns became forage for dairy cattle. While the Steeles made cheese, most new dairymen produced butter, a commodity that became California’s other gold. Less than a decade after Clara first made her cheese, Marin County became the major contributor of dairy products in the state, and soon the Point Reyes dairy industry became famous.

The Shafter family of Oakland and San Francisco owned the most famous, successful and long-lived (1857–1939) agricultural entity in Marin County. Two brothers from Vermont, James M. and Oscar L. Shafter, arrived in San Francisco as attorneys in the early days of the Gold Rush. The Shafter firm represented a party in the struggle over ownership of Rancho Punta de los Reyes and its larger sobrante (leftover land), and ended up owning the entire 60,000-acre property. Among their inherited ranch tenants were the Steeles and, no doubt inspired by the successful dairy pioneers, the Shafters took personal control of the land grant.

With the help of Oscar’s son-in-law Charles Webb Howard, they divided up the peninsula into 30 dairy ranches. The partnership labeled the parcels with letters of the alphabet, built up-to-date ranch buildings and leased them out. By 1870, the entire Point Reyes Peninsula was one dairy ranch with 10,000 cows, referred to as the largest “Butter Rancho” in the country. The Shafters personally inspected the dairies and expected the utmost in efficiency, cleanliness and quality from their carefully selected tenants.

A thoughtful tenant could save the money to buy a ranch of his own somewhere else. Large land grants in Marin and Sonoma were gradually subdivided, offering new arrivals or former tenants small ranches for purchase. For instance, Henry Wager Halleck, Abraham Lincoln’s chief of staff during much of the Civil War, broke up his large portion of Rancho Nicasio into smaller 500- to 1,500-acre ranches and sold them. These small dairies established the pattern of land ownership that remains intact in the rural parts of the counties today.

By the end of the 19th century, the American gold-seekers of the 1850s were mostly supplanted by people from Ireland, southern Switzerland and the Portuguese Azores, all escap- ing poor conditions at home and searching for a good life in the United States. By 1900 most ranches in the county were operated by immigrants.

At first, certain areas attracted certain nationalities—for instance, the Irish preferred Point Reyes, the Azoreans southern and eastern Marin, while the Swiss congregated in the central part of the county and along Tomales Bay. These folks from the old country raised American children, were good neighbors and even intermarried at times. And most continued dairy work through the generations.

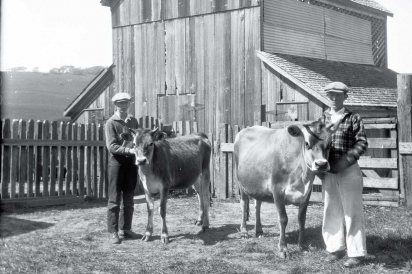

Life on a North Bay dairy ranch differed little from that on a dairy farm elsewhere, except for the fine climate and good conditions for pasturage and marketing. Summer fogs kept the grasses viable longer in the coastal area, and animals did not need shelter from freezing winters. Forward-thinking dairymen imported fine bulls and dairy cows from the East Coast or Europe.

Typically, the whole family pitched in with farm work, and most families were large: eight to 10 children were not uncommon. Not only did the cows need to be milked twice daily, they had to be gathered, doctored, separated and slaughtered. Most families tended vegetable gardens and orchards for their sustenance, as well as feed crops for their animals. Water systems and fence lines needed constant attention, not to mention the daily chores of washing clothes, tending chickens, repairing buildings and preparing food for the family and hired help.

Even decades into the 20th century, lack of rapid transportation prevented most North Bay dairies from shipping fresh milk to market. Butter and small amounts of cheese remained the major exports into the 20th century. Farmers produced butter by separating the cream from the fresh cow milk. Still- warm milk in the pail was carried to the creamery—a feature on all dairies—where it was strained and set out to separate in a wide pan. During the 1880s, power-driven DeLaval separators replaced the ancient pan-separating methods. The cream was then churned in large rotating boxes, invented on Point Reyes by Oliver Allen. Usually, a horse or mule powered the churn, later a steam or gasoline engine. No one was interested in the skim milk; it was fed to the pigs.

The buttermaker pressed the buttermilk out of the creamy mass, salted it and packed it in wooden boxes. It could be stored in the cool cellar or transported to market by wagon, schooner or train. Marin’s butter, especially that made in Point Reyes area, became the standard of high quality in gourmet hotels and restaurants in San Francisco. Some unscrupulous entrepreneurs took advantage of Marin’s good name and labeled inferior butter with the Point Reyes trademark.

And so Marin County, smallest of the original California counties, led the way in production of fine dairy products for half a century. As the industry and demand grew, Sonoma, Humboldt, Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties joined the new “gold” rush. When large tracts became available in the Central and San Joaquin valleys, the Marin dairy indus- try lost its statistical stature, but not its life or reputation for quality. Marin’s dairies passed down through generations and many are still in business under the same name today.

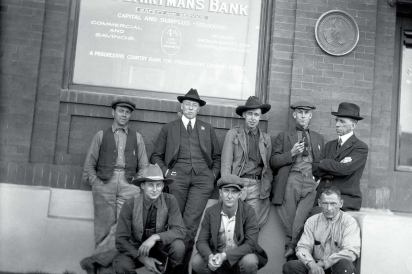

Success in dairying led to the establishment of small rural towns and local banks with dairymen on their boards. These villages in rural Marin and western Sonoma counties each had their own character, much of which remains to this day. And not only were there cow ranches: The Novato Valley was blanketed in orchards; vineyards covered acres of hillsides around Fairfax, Larkspur, San Rafael and Novato; hay and grains grew in reclaimed marshlands on the eastern fringe of Marin and the southern sloughs of Sonoma, shipped to the city on flat-bottomed scows. Corn, wheat, potatoes, even a number of thriving commercial flower farms dotted Marin at various times.

In the 1920s, Point Reyes became a major growing area for artichokes, grown by Italian immigrants, and peas farmed by Japanese. World War II ended those industries abruptly, with coastal access restrictions for the former and internment for the latter.

Eighty to a hundred years ago California’s dairy industry experienced a number of upheavals with the tightening of sanitary regulations and leaps in transportation and technology. Sleek concrete and steel sanitary milking barns replaced the venerable wooden cow barns, and soon trucks came to take away fresh milk rather than butter or cream. The indus- try turned highly profitable for many dairymen, and organizations like dairy co-ops and private creameries offered often-lucrative production contracts. The industry grew in political power and also became more of a monoculture of Grade A milk with fewer signs of individuality. Some went into cheesemaking after 1900, but only a few survived. Jefferson Thompson’s family-run cheese factory at Hicks Valley, founded in 1865 and maker of the well-regarded Rouge et Noir brand, persisted in cheesemaking and is now the country’s oldest in continual production.

The Golden Gate Bridge and postwar development put Marin and Sonoma’s dairy industry under the gun, as large dairies like Freitas’s at Terra Linda, Bettencourt’s at Greenbrae and those in east Petaluma were transformed into suburban neighborhoods. The coastal ranchlands were to be next. Under such duress, a surprising but determined coalition of environmentalists, farmers and politicians worked to preserve what agriculture was left in Marin, first establishing A-60 zoning that restricted development on agricultural lands

in west and north Marin, and then creating an innovative organization whose success has inspired others all around the country: the Marin Agricultural Land Trust, or MALT.

In the 1970s, dairy farmer Ellen Straus and biologist Phyllis Faber sat at farm kitchen tables around the county and talked about the adversity being faced by dairy families. “Dairies were going out, the kids were leaving, and all of the dairies from east Marin were gone,” recalled Faber recently. “Ellen and I were watching helplessly and really wanting to find some answer that would put a stop to it.”

“Dairying is really hard work,” Faber continued, “and unless there was a future generation interested they were going to sell their land for their retirement. We needed to find a way to make that land secure, so that became our quest.”

To add to the stress, the state proposed stricter protective zoning on the coast that would effectively split the county in two, something that neither ranchers nor the county wanted. “It was a unique moment in time for this county, and without that gun to the head of the county they would have never picked up a crazy idea like buying development rights,” Faber recalled.

Straus and Faber founded MALT with a mission to slow or stop the disappearance of productive ranches for conversion into subdivisions, estates or hobby farms. They gathered interested and progressive people like dairy rancher Ralph Grossi, county supervisor Gary Giacomini, planning commissioner Jerry Friedman and supportive ranchers like Boyd Stewart and Willie Lafranchi. The organizers created a system that paid ranchers for agricultural easements that would keep the land for farming in perpetuity. Since its founding in 1980, MALT has saved over 44,000 acres and 69 family farms to date, but their work and that of other agencies and organizations is far from done.

“I think that MALT has played a role not always by design, but because of life,” said Faber. Ellen’s son, Albert Straus, took advantage of the program, using the money from MALT to convert his family’s dairy to organic (the first organic dairy west of the Mississippi) and establish a commercial creamery that is today known as Straus Family Creamery.

“Nowadays a dairy rancher almost has to be organic to survive; the productivity of the big dairies in the Central Valley just swamps them,” she noted. “The light bulb went on for our dairy ranchers, and so almost every one of the other ranchers has now indulged in some value-added program in their ranching operation. And it was a MALT dairy rancher [Albert Straus] that showed them how.”

Today, Marin and Sonoma’s dairy industry has diversified, with milk products originating not only with cows but sheep, goats and water buffalo. The North Bay now has the largest concentration of artisan cheesemakers outside of Vermont, and many more milk dairies are going organic. Some are new residents seeking opportunity in our green fields, and some, like the Lafranchi family of Nicasio Valley Cheese Company, can trace their roots back over 150 continuous years in Marin dairying.

As the birthplace of California’s dairy industry and an innovator throughout its history, most of Marin County remains a picturesque pastoral landscape after generations of productive use. Residents old and new appreciate the historic landscape and— hopefully—respect and honor the brave conservation efforts that effectively drew a protective line separating suburban east Marin and the agricultural open spaces of west Marin.

Preserving the agricultural legacy of Marin has ensured a more healthy and appealing place to live, and for that we should perhaps raise a glass (of milk?) to the memory of Clara Steele.