Pomegranates: Harvest is On the Horizon for History's Most-Hailed Fruit

Botticelli and Cezanne painted them. Homer and Chaucer wrote about them. It’s even rumored that Eve was tempted by one. The Egyptians were buried with them to ensure rebirth and the Greeks believed Hades used them to keep Persephone captive, as his queen, in the Underworld. Long considered a powerful symbol of life and fertility, with its abundance of seeds and flowing crimson juice, the pomegranate is the mythical muse of fruits.

Most people can recognize apple and cherry trees but struggle to envision the plant that bears the pomegranate. Vermont doesn’t know pomegranates; neither does Connecticut. As a transplant from New England, it’s safe to say I never saw a pomegranate growing in a garden during my youth. Even after I moved to California they still remained elusive to me, so I welcomed the opportunity to do some research for this article and acquaint myself with this beguiling, transcendent fruit.

The pomegranate plant is a member of the Punicaceae family, which includes only one genus and two species. It is a deciduous shrub (or small tree if pruned accordingly), with a round growth habit, spiny branches and mottled bark. The plant can reach as high as 20 feet tall–although most top out at about 12 feet. Its small, oblong leaves showcase the star features: the magnificent orange-red tubular flowers with ruffled petals and the spectacular, surreal-looking fruit. Harvested in late fall to early winter (depending on the variety), the pomegranate fruit has a reddish, leathery skin with a puckered calyx crowning the base. The pomegranate is not only revered for its fruit, its showy flowers are magnetic to hummingbirds, bees and other desirable garden guests, making them a great choice for a habitat garden.

From Persia with Love

The name “pomegranate” derives from the Latin pōmum meaning “apple” and grānātus meaning “seeded.” Native to Iran (formerly known as Persia) and the Northern Himalayan region of India, scholars trace the pomegranate back as far as 3000 B.C., making it one of the first cultivated fruits in history. During ancient times, it was aggressively planted throughout the Mediterranean regions of Asia, Africa and Europe, but it did not in land in California until around 1769, brought by Spanish settlers.

The name “pomegranate” derives from the Latin pōmum meaning “apple” and grānātus meaning “seeded.” Native to Iran (formerly known as Persia) and the Northern Himalayan region of India, scholars trace the pomegranate back as far as 3000 B.C., making it one of the first cultivated fruits in history. During ancient times, it was aggressively planted throughout the Mediterranean regions of Asia, Africa and Europe, but it did not in land in California until around 1769, brought by Spanish settlers.

Still today, the pomegranate plays a central role in many cultures around the world, used in ceremonies celebrating rites of passage as well as in everyday meals. By contrast, American consumers have been slow to embrace the fruit. Its tardy invitation to our tables is usually attributed to the fact that excavation of the edible portions of the fruit is, well, labor-intensive. Extracting the juice and seeds can be time-consuming and messy, and with so many other, more convenient fruits, why bother?

That sentiment changed in the 1980s, when studies were published touting the pomegranate’s powerful health benefits. The pomegranate is packed with antioxidants, vitamins, potassium, folic acid and iron–a top-notch “super food.” Once word got out, pomegranate products began popping up everywhere. Surely you have seen a bottle of POM Wonderful or one of the other packaged pomegranate juices so common on market shelves these days, or perused a restaurant menu featuring pomegranate purées, sauces and seeds. The pomegranate has definitely gained traction–not quite mainstream status, but its market share among U.S. consumers is definitely on the rise.

The pomegranate’s share of U.S. agricultural land is increasing, as well. There are two predominant hubs for commercial pomegranate cultivation in the U.S.: Arizona and California. In California, the mecca for pomegranate agriculture is the San Joaquin Valley, specifically Tulare, Fresno and Kern counties. The expansion of pomegranate production in California over the past half decade has been impressive. According to the Census of Agriculture, in 2007 the United States had 599 farms growing pomegranates on approximately 24,517 acres. By 2010, it was estimated that the San Joaquin Valley alone had 22,000 acres planted in pomegranates. The varieties that pack those acres are largely: Ambrosia, Early Foothill, Granada, Ruby Red and Wonderful.

How Does YOUR Garden Grow?

The pomegranate may have an impressive resume, but can you grow them yourself?

When talking plants, “cultural requirements” refers to the set of conditions necessary for a particular plant species to thrive. So, what does a pomegranate need to be happy and prolific?

Here are the must-haves:

- Climate: Pomegranates require full sun and dry heat. Accordingly, they thrive in Mediterranean climates, where the summers are dry and warm and the winters are mild.

- Soil: They do best in well-drained soil. Ordinary soil is just fine; they will even tolerate a more alkaline soil.

- Water: Once established, the pomegranate is relatively drought-tolerant, although irrigation will keep fruit production high.

- Pruning: The natural pomegranate growth habit is shrub-like, but they respond well to pruning if another shape is desired.

- Feeding: Regular applications of compost are the best way to deliver a steady flow of vital nutrients to your pomegranate trees.

Their love of dry heat and sun, coupled with their frost sensitivity, makes growing pomegranates in Marin tricky because it has so many unique microclimates. Napa and Sonoma are better suited because their climates are more consistently Mediterranean. Enter Julie Johnson, winemaker and owner of Tres Sabores Winery (www.tressabores.com) in Rutherford (Napa County). Julie boasts over 60 pomegranate trees on her 35-acre vineyard. The property is a sun-soaked alluvial fan, nestled into the hillside, prime for pomegranates (and grapes). Recently, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Julie over some magnificent Tres Sabores 2010 Sauvignon Blanc to talk not grapes, but pomegranates.

Here are some of the many insider tips on growing (and enjoying) pomegranates that she offered:

Edible Marin & Wine Country: The obvious question first: Why did you choose to plant pomegranates?

Julie Johnson: I’ve always loved them–it’s that simple! I can remember eating them as a treat as a kid growing up in Palo Alto–it’s a well-known tool for moms who need to keep a young one engaged in an activity for a while! They have such a great presence in a garden–such versatility. Best assets: easy to grow, great disease resistance, deer don’t like them, my sheep don’t like them (unlike my roses), relatively low water needs. They are phenomenal habitat plants; the pollen in the blossoms attracts bees–obviously important to a garden and orchard setting–and the nectar in the blossoms attract hummingbirds, insectivores crucial to keeping bugs under control in any setting, vineyards included. After all of that–they reward the grower with fruit at the end of the fall.

EM&WC: What are the essential things anyone thinking about growing pomegranates should know?

JJ: They need space, sun and good drainage, and a half pound of good compost dug into the base of the tree every year. EM&WC: What has been the trickiest part about planting/ harvesting pomegranates?

JJ: Young transplants need time to “heel in” and get comfortable with their site before they really start producing. Some of my cultivars are more sensitive to frost than I would have hoped. They bear [fruit] on old wood–which makes what pruning you do a little trickier. They don’t need much pruning unless you want to give them more focus in your landscape.

EM&WC: What amount of fruit do you consider a good harvest?

JJ: Stories of yields of “100s” are legion. Many of mine are still maturing, but the ones I’ve had planted for 20+ years yield at least 30–50 [fruits] per tree.

EM&WC: The most rewarding moment you can remember related to your pomegranate trees?

JJ: Just seeing things work the way they’re supposed to– naturally attracting hummingbirds, blossoms covered with bees–the cycle working.

EM&WC: What has been the most unusual or unexpected thing you’ve learned about pomegranates?

JJ: The astounding variety of cultivars. I’ve seen them in Mexico, in Granada [Spain] (of course), in Isfahan [Iran] and Tashkent [Uzbekistan]. UC Davis has a nursery of exotic and experimental cultivars. A nursery in South Carolina specializes in them. A collector in Australia has hundreds of varieties. In California–it’s not surprising when I hear about a friend who’s just moved into an older home (anywhere–Berkeley, Modesto, Temecula, etc.) and has “discovered” a pomegranate tree in their backyard. I think they were a bit like roses and grapes–in the old days, people brought cuttings with them when they moved. It’s said that the Spanish padres originally brought pomegranates to California. So, while they’re not native plants, they’ve certainly found a great home here. The real, and astonishingly simple, revelation came about 15 years ago. I was showing my wine to a chef in Los Angeles and we got to talking about pomegranates. He showed me a technique for rapidly knocking out all of the fruit seeds. Voila! Another minor revelation that made great sense to me–just as with grapes–is that if you find the right nutrient balance in the soil, practice deficit irrigation and harvest when ripe, you get the best, most concentrated juice.

EM&WC: Pomegranates have a rich history. They have served as offerings to gods as symbols of fertility. Some even say they have mystical healing powers. What’s your favorite pomegranate lore?

JJ: You’ve got it. I think that once it was discovered wild in the fertile valleys of greater Mesopotamia, it was so exotic, so intense–it just had to be a revelation to anyone who came across it. At first, before people discovered that they could fairly easily propagate and cultivate the plant, it was probably fairly rare–which added to its mystique, of course. Can you imagine the sensation caused by a knight returning to Northern Europe from a crusade with a handful of cloves and a couple of pomegranates in his saddlebag? The plant adapts to so many environments, even very severe conditions, the fruit can be stored for fairly long periods of time and I have no doubt that ancient practitioners of plant sciences discovered early on that the juice was highly restorative. The fruit can be fermented, distilled and it’s acidic so it makes a decent preservative.

EM&WC: Any plans to use your pomegranates commercially?

JJ: We currently offer, only through the winery, a pomegranate- infused golden balsamic vinegar in 2 ounce and 7.5 ounce bottles. It’s an amazing addition to a sauce or salad dressing. We are also planning to produce more of our “Fire- Roasted” Zinfandel-Pomegranate Marinade.

EM&WC: Favorite pomegranate recipes?

JJ: My pomegranate margaritas! As I got in my car for the drive home, inspired by Julie’s infectious enthusiasm and sunny disposition, I knew with certainty that there would be many a pomegranate in my future. The season is upon us; the king of fruits is ripe and ready.

Eat. Drink. Be healthy.

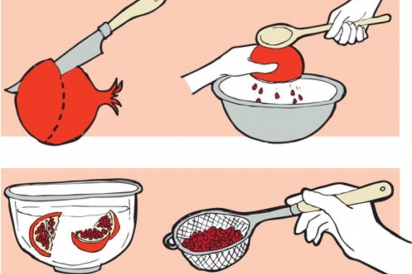

SEEDING POMEGRANATES–TWO WAYS.

1. Knock it.

Cut your pomegranate in half, between the crowned base and the top.

Holding the cut side down over a large bowl, firmly knock the pomegranate with the back of a wooden spoon. Give it a few good whacks while rotating the pomegranate and let the seeds fall into the bowl.

Pros: Fun for adults and kids alike. AND fast!

Cons: The juice can splatter, so wear an apron.

2. Submerge it.

Fill a bowl ¾ full with water.

Cut your pomegranate into pieces and submerge it in the water.

Working underwater, gently remove the seeds by pulling the pomegranate apart.

The edible seeds will sink, while the skin and spongy white tissue holding the seeds will float.

Skim the debris off the top and strain out the seeds.

Pros: The juice can’t splatter since it’s submerged.

Cons: More time-consuming than “knocking.”