Front Porch Farm Brings to Life Integrated Regenerative Farming

One Couple Sees a Lot More than Wine Country in Healdsburg’s Prime Growing Region

“What I stand for is what I stand on.”

That spare sentence by Wendell Berry, the American poet laureate of environmentalists, small farmers and advocates of sustainability, has become a kind of gospel, at once simple but enormously complex. The idea—that the soil beneath our feet ties us to the entire cosmos of our own principles—packs a wallop. And it might well have been the call Peter and Mimi Buckley answered when in 2010 they purchased a large parcel of beautiful, arable land along a northeastern stretch of the Russian River.

They named it Front Porch Farm and, fittingly, what the Buckleys stand for lies right off the front porch of their unassuming and thoroughly charming one-story farm house that rests near the shade of two aged live oak trees.

Once you actually find it (I first cruised past the small hand-painted sign off Healdsburg’s Bellevue Road and ended up on a dirt road behind a Seventh Day Adventist boarding school), the Buckley’s sprawling 110-acre property sits in a fertile, sun-kissed valley along the winding river, banked by hilly vineyards that give way to mountain forests. This is definitely an Eden.

The property is perfectly situated to benefit from an optimal and widely coveted microclimate. Drenched by the constant Sonoma sun during the day, the hills and lowlands are cooled in the evening by the coastal air that slips in and over the valley from the west. All is kept in moderation by the presence of the Russian River, which also feeds the farm’s aquifer.

These are the conditions that make for a wine grower’s paradise—hilly variegation with multiple directional exposures and heat and moisture levels that remain largely predictable. So it was at first surprising to find only a relatively small proportion of the Buckleys’ land—12 acres on the hillside—planted with vineyards. The previous owner had covered the place with them, but the Buckleys got to work tearing out the preexisting vines, including eight acres of 30-year-old Sauvignon Blanc, much of which had either died or was in poor health, as well as newer Chardonnay plantings that had been designed for maximum fruit production and spoke to the sort of unremarkable mono-crop cultivation that the couple was dedicated to working against. They then began the selective process of replanting the hills with smaller blocks of Rhone varietals that better suited the land and can produce, under the right care, gorgeous wine.

That left the choice bottomland fields that form the heart of the farm for everything else. And it is that “everything else” that Peter and Mimi Buckley had spent a lifetime preparing to explore. The Buckleys had committed to doing something that doesn’t happen very often in the wine-crazed Sonoma and Napa valleys—in a sense de-emphasizing their wine-bearing crops while attending to a greater vision of a far more bio-diverse, balanced and ultimately stable and sustainable idea of farming. They were interested in returning the soil to its own best and truest expression of health, and then finding out what could happen in it.

The Buckleys had the means—and you’d need them to be able to purchase such a tract of land in Healdsburg—to take on this venture. Peter was a senior executive for years at Esprit Corp. Mimi and Peter lived in Germany while he ran Esprit’s European operations, then moved with their three children back to the Bay Area, settling in Marin County. What came next began to pave the way for the farm. The Buckleys got into education, forming a Rudolf Steiner–based school, the Greenwood School in Mill Valley. Peter founded the Berkeley-based David Brower Center and co-founded the Center for Ecoliteracy, a nonprofit dedicated to bringing ecological education into K–12 curricula. The couple were actively exploring and refining their ideas about the farm that was to be.

Once they bought the property, they brought in organic farming guru Amigo Cantisano to consult (Cantisano founded the West’s largest sustainable farming conference, the Ecological Farming Conference, decades ago), and the couple’s commitment to the underlying principles of biodynamics and organic farming were at last put to action.

The Buckleys began painstakingly transforming the farm’s flat acreage, planting fields of flowers and vegetables, rows of fruit and nut trees and acres of heritage grain. They introduced new animals and built outbuildings and sheds to provide the space and shelter for their staff to work on experiments with heirloom seedlings, farming methods and equipment. They created a shaded communal space that would become a respite for crew, family and friends at all hours.

It was a relief to my eyes to take in the scene: Instead of an unyielding gridlock of vines that sometimes seem to cover every available inch of cultivable Sonoma and Napa, there were the vivid colors of a flourishing flower farm aside wide expanses of wheat and alfalfa fields, roaming chickens, olive trees, beehives and rows of berry plantings all on center stage.

Peter led me through gorgeous blackberry bushes, one varietal after the next caned in carefully tended tiers, all in a sort of ongoing experiment to find the richest, sweetest, wildest tasting fruit. We commenced tasting the various berries right off the bushes in an ad hoc piece of research that did not require any persuasion for this participant. The test results came in immediately: The berries were amazing.

And the nuances between the three types of berries Peter shared with me were bright and clear—the favorite being Triple Crown, huge and shiny berries warm in the hand from the sun that burst with a wild, jammy depth, at once tart and sweet and layered with flavor. Exercising restraint became a challenge. Unlike most fruit, Triple Crowns don’t continue to ripen after they’re picked. They must be harvested at their peak of flavor and enjoyed right away (this is why those in the know arrive early to the Thursday and Sunday Marin Civic Center Farmers’ Markets in San Rafael when Front Porch brings in its blackberries).

Behind the blackberry cultivars lie the long flat fields of wheat—heritage grains with which the Buckleys are also in continuing experiment. Their goal here is in a way to turn back the hands of time by sourcing and introducing grains that thrived for centuries in similar growing regions in Europe and produce far more flavorful and nutritive breads and pastas than the mono-crops we are used to consuming with their dull, flat and one-note flavors and textures. This land can do it, and it seems to want to. Special varieties of farro, oats, rye and einkorn are being introduced and watched closely.

Mimi Buckley, whose seemingly indefatigable passions extend to architecture, design, pottery, education, spirituality and writing (she’s the author of the lovely and inspiring The Road Home: A Letter to My Children, 2013), presides with Zoe Hitchner over the farm’s considerable flower-growing operation. It’s an imaginative, 100% organic and, unsurprisingly, very active operation.

Front Porch grows flowers year-round (except for December and January, when focus turns to fresh herbs, dried flowers and bay laurel wreaths), selling to florists, markets, the farm’s own booth at the farmers’ market, as well as custom orders for events and weddings. Mimi provided a rundown of at least 35 by name, hastening to add, “we grow many other types of flowers as well.”

There’s a term for the farming they do at Front Porch. Johnny Wilson, their energetic farm manager, hopped off his ATV-ish buggy, dusted himself off and cheerfully enlightened me: Integrated Regenerative Farming. Each member of the Front Porch crew is a graduate of the esteemed University of California Santa Cruz’s Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems program and tends with a passion everything from flowers, vegetables, fruit orchards and the vineyard viticulture to the various and ongoing experiments that the Buckleys are constantly advancing.

The Buckleys have also devised a credo of their own: “A farm should be a harmony of nature, culture and place.” That ideal of harmony has been their lodestone and kept the couple happily engaged in the continuing invention of Front Porch. These are people devoted to the well-being of the “whole” and to creating and managing an enterprise that operates as one happy family engaged in a greater mission. Shared meals with friends, family and farm staff often spill well into the night and include playing music under the stars.

Integration with their community is also a priority. The Buckleys say they are inspired by noted environmentalist Wes Jackson, whose embrace and evangelism of what he termed “holistic farming” includes the notion of “putting the culture into agriculture.” Having the financial wherewithal to experiment with heirloom varietals and farming methods allows the Buckleys to assume the risk inherent in some of these undertakings, sharing lessons learned with neighbors and other farming friends. This includes helping to form a Nor-Cal Grain Growers Group, where farmers, bakers and equipment vendors exchange information about their successes and failures, and also share equipment.

It’s the through-line of what’s being cultivated on the farm’s soil that completes the picture: the markets. Front Porch has a robust presence at San Rafael’s Marin Civic Center’s farmers’ markets, where you can also taste and purchase their wines. Their heritage wheat is used in dried pastas produced by Community Grains, and is available as stone ground flour at Healdsburg’s SHED. Prosciutto from their prized Cinta Sonoma pigs (see sidebar) is currently found on the menus of destination restaurants such as San Francisco’s celebrated Quince.

This has all been a considerable investment. Getting to economic sustainability will take some time, but the cooperative spirit that the Buckleys embrace and practice with their neighbors is solution-building in itself.

“I hope,” Peter says, “that we keep improving at what we do, and that the health and vitality of the farm, especially its soils, does the same.” Ideally, bringing the fruits of their labor to the marketplace should be an equitable match of output to demand. “We are a small farm, so if we are doing our best we should be sold out.”

And these are products that, by their very nature, must find a local demand. Those wonderful Triple Crown blackberries that must be eaten within a day of picking couldn’t be handled by large distributors with huge inventories and large transport timelines.

“In general,” Peter says, “whether with grains, fruits or vegetables, we are looking for products that are special. We have, at our scale, a competitive advantage. Maybe a variety of broccoli is not a heavy producer, but it’s sweet and tender, so again we can grow that where the large-scale producers are more oriented to their major customer price points. And sometimes things just grow really well here, like Baby Gem lettuces or the Butternut squash.”

Balance and sustainability, health and biodiversity of land, a dedication to continuing education and to the well-being of community. These are more than ideas and trend-lines at this point of Sonoma’s evolution as a farming mecca, and more and more like ways of life. I left Front Porch Farm enchanted by the way of life that was being expressed there.

Mimi seemed to perfectly sum up the benefits of the world they inhabit up there in another simple sentence: “At the end of the day, Peter and I always take a swim in the river.”

THE CINTAS

They wear fetching wide white sashes. They feast only as true locavores do, dining exclusively on the wild chestnuts and acorns of their native terroir. They are exceedingly valuable, very cute and almost outlandishly impossible to budge out of out of their native province in Tuscany. They are highly fashionable pigs, and they are massively in demand.

Meet the Cinta pigs of Siena, or Cinta Sineses. Peter and Mimi Buckley could write an operetta about their experiences trying to bring the pigs from Italy to the United States and establish them at Acorn Ranch, Front Porch’s sister property comprised of 2,000 acres of mostly mixed oak forest in Mendocino County. The Cinta breed is rare, ancient and revered for the nuanced and richly flavorful meat it produces—prosciutto and salumi that chefs (and consumers) die for.

After almost two years of occasionally mind-numbing negotiation and palaver with an array of Italian authorities, the Buckleys at last had a deal. As long as they could assure a strict chain of custody for the transport of the Cintas along with a pact to retain the genetic integrity of the breed, the pigs could come to California. They would also have a new name once the introduction was complete: the Cinta Sonoma. Guaranteeing the chain of custody of the pigs was a trial. They had to be completely untouched by anything or anyone that could endanger their well-being or compromise their heritage integrity.

Thankfully, the Buckleys were up for the task and elaborate travel arrangements were made to get the Cintas safely and securely to California, where they now happily roam, root and forage to their hearts’ delight. The ethical treatment of these animals is as important to the couple as the health and integrity of their other plants and animals. The pigs live longer lifetimes in habitats as natural and wild as possible, all while under the protection of handlers who take great care with them. With any luck, the success of the Cintas might pave the way for more such enterprises.

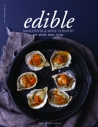

Jaime Prado, who cares for the Cinta Sonoma at Acorn Ranch, took the gorgeous photograph of the porcine beauties that graces the cover of this issue. He definitely has a way with pigs.