Growing A Thriving Food System

KITCHEN TABLE ADVISORS SUPPORTS LOCAL PRODUCERS

When they lived in Thailand, Koy Saechao’s parents farmed to feed their family, as well as to earn cash to pay for their other needs. They grew rice and vegetables like bitter melons and long beans, as well as maintaining fruit trees. They also raised cattle. So when the family moved to Oakland when Saecheo was 7 years old, it seemed only natural that they would continue to grow their own food. Producing their own not only saved money, it lessened the new immigrants’ burdens of navigating a foreign food system and language barriers— finding familiar ingredients was as simple as stepping into their yard.

When a friend of Saecheo’s father offered to sell them a strawberry farm, the family took up farming for a living again. These days, in addition to raising their own chickens and pigs and cultivating plots of Asian vegetables, they support themselves by growing 18 acres of organic strawberries in Petaluma.

Stony Point Farm is in many ways a prototype of why small family farms are critically important. The Saecheos’ farm not only provides an avenue for the family to earn a livelihood doing what they know and love, the certified organic operation has positive impacts that ripple throughout the entire region. The Saecheos are active members of their community—operating a farmstand during the spring and summer months. Their produce, much of it culturally relevant to other Southeast Asian immigrant consumers, is also sold at regional grocery stores and farmers’ markets, and their perfumey Albion and Chandler strawberries pop up on the menu at the local coffee roaster down the road. During planting season, other local farmers come to Stony Point to share the work, and the Saecheos return the favor. Koy Saecheo’s own young children also enjoy farm life and relish burying seeds in their backyard, developing into the next generation of conscious eaters and environmentalists.

For all of these reasons and more, Bay Area chefs and eaters, and even mixologists, love and appreciate small-scale local farms. The local food media certainly does. Still, despite the social success of many of these farms, financial viability remains a struggle.

“It’s like living paycheck to paycheck, but at least you’re planting your own food,” said Koy Saecheo when I asked her what it was like to make a living from farming. Like the other people working behind the scenes of our lauded restaurant and food industry—the cooks, servers, delivery drivers—farmers often struggle to earn enough to live here.

Enter Kitchen Table Advisors (KTA), an organization whose mission is to provide small-scale farmers and ranchers with access to the information, tools and resources they need on their path to become resilient and viable businesses. KTA supporters and staff understand that the effects of their work extends well beyond the 50 farms and ranches the organization has directly supported since its founding in early 2013. By helping these individual enterprises, they are bolstering the food security and overall economy of our entire region.

Farming is a uniquely costly business. Unlike tech start-ups or organizations with remotely connected workers, the more a farm grows the more resource intensive it becomes. Access to affordable land is one of the largest barriers for aspiring farmers in the Bay Area, and land security can be tenuous even for current farmers at the mercy of landlords who may decide to sell the property or decline to extend a lease. Farming equipment is costly to acquire and maintain, but necessary to scale. Finding enough labor is always an issue, and expensive when you do. But while the cost of doing business is constantly on the rise, the consumer market isn’t necessarily friendly to an increase in prices. This leaves small-scale farmers and ranchers with extremely thin profit margins.

In their latest impact report, KTA reported that their clients went from earning $18,000 per year, on average, to $30,000 per year after receiving KTA assistance. A 60% increase is quite impressive, but even $30,000 in earnings does not provide long-term financial sustainability for a business in the Bay Area.

“We know that they aren’t going to close their doors next week, but that’s still going from scraping by to eeking something out,” said Paige Phinney, KTA’s regional director for Sonoma, Marin and Napa counties.

This isn’t an issue unique to the Bay Area. In a food system that is increasingly set up to favor multinational corporations and large agribusinesses, small to medium-scale farms are being squeezed across the country. Since 2013, America’s farmers and ranchers have experienced a nearly 50% drop in net farm income. Last year, farmers signaled a state of emergency and warned of a crisis reminiscent of the 1980s, when hundreds of mid-scale farms were driven out of existence.

KTA provides a free three-year (and often beyond) commitment to the farms they work with, providing one-on-one advising by KTA staff about once a month. They work primarily with first-generation farms and ranches that are organic or pasture-raising animals, and are at some sort of inflection period in their business—a desire to scale up or seek new market channels, for example. The farmers and ranchers they select could also be considered changemakers in their respective fields.

“We work with folks who are thinking about the whole ecology around running a farm: the people, the plants, the animals, the soil— all of it working in tandem. They have passion for the whole system,” said Daniella Sawaya, KTA’s community engagement manager. These are individuals who are on the cutting edge of ecological horticulture, who employ local residents, who donate their time and money when their neighbors are in need, like during the 2017 and 2018 fires.

A big focus for KTA is working toward a more fair, equitable and accessible food system—for everyone involved; 80% of their clients are women and people of color.

“It’s so hard to make it as a farm as is, and the obstacles are even greater for women, for folks of color, for immigrants, all the folks that are under-resourced in general and especially in agriculture,” said Sawaya.

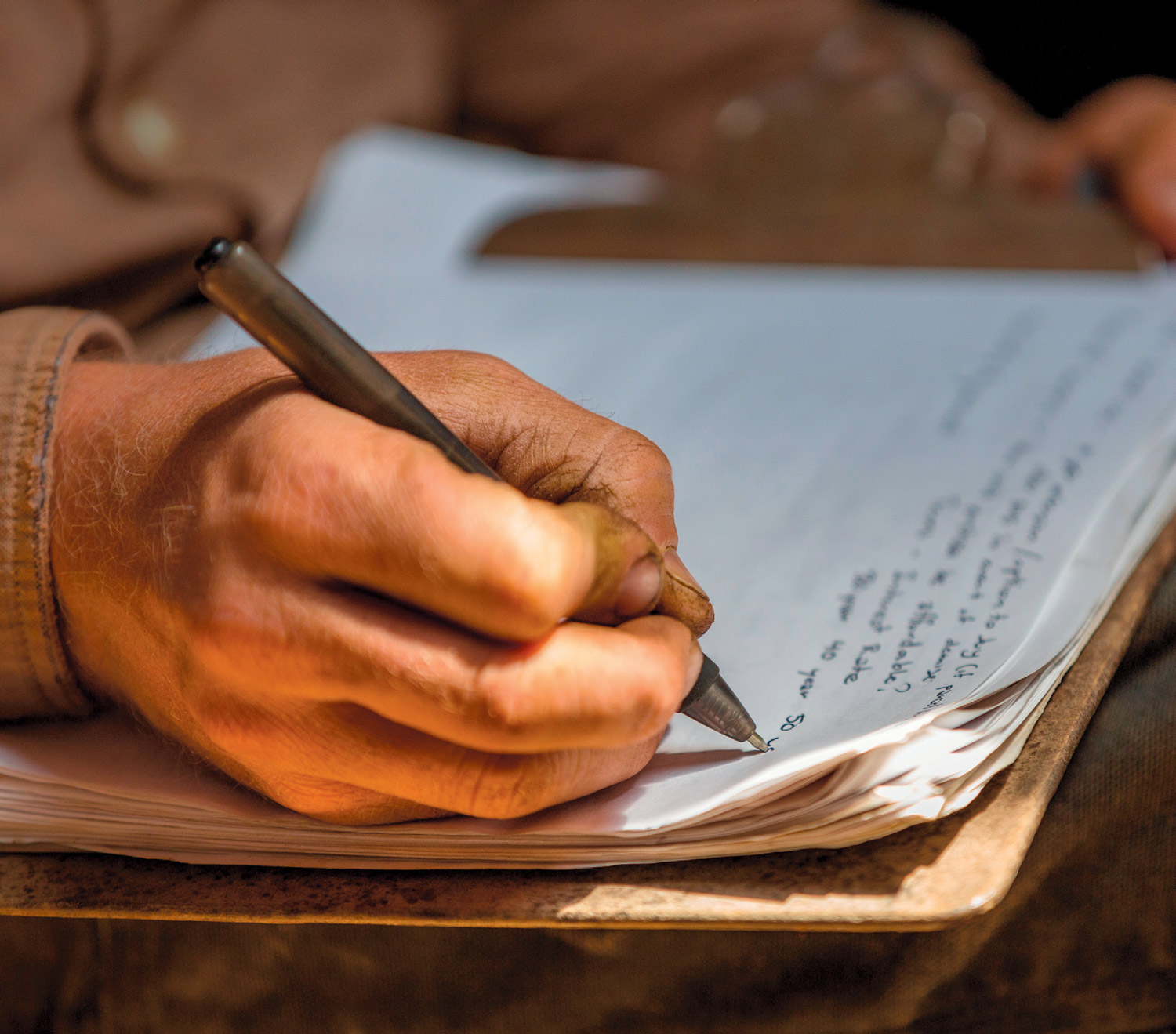

Advisors primarily step in to help these farmers and ranchers take a bird’s eye view of the business when it comes to issues of land, capital and markets—a luxury most farmers don’t have with their heads down in the strawberry patch. Their advice can be as mundane as improving record-keeping systems, or as personal as family planning (there is no maternity leave for small farm owners, after all).

By having someone else examine data and help make decisions, farmers are less likely to continue plowing through the day-to-day, and instead have the capacity to make strategic moves for long-term financial sustainability. Stony Point Farm, for example, had been farming “beyond organic” for years, but recently worked with an advisor to obtain organic certification—allowing them to nudge up their prices. They have also received general financial planning and organizational advice.

For Libby Batzel, co-owner of Beet Generation farm in Sebastopol, KTA came into their business at the perfect moment. Batzel and her wife, Ali Levesque, opened the farm nine years ago, and at year five were considering how to incorporate a value-added product.

“We were just starting to look into vegetable pastas, and they were really critical in helping us understand the value of it,” she said. The KTA team connected them with resources to help label, market and find distribution channels for the pasta. According to Batzel, sales of their colorful Beet Generation Kitchen Pasta have “blown up” in the last year. They can barely keep up with the demand.

Farming is often a solitary business, and Batzel added that KTA’s work to create community by connecting farmers to each other and to other networks has also been a great benefit. The organization, she said, is closing the gap between farmers and the industry that wants to support them.

Batzel also points to the fact that in order to build a healthier regional food system it takes several actors working in tandem. The farmers I interviewed for this story also work with FEED Sonoma, a for-profit business that purchases cleanly grown agricultural products from 50 small farms in Sonoma County and transports them to local buyers— including restaurants, grocery stores, schools and caterers—within 24 hours of harvest. It was Tim Paige, FEED’s co-founder, who echoed the advice of the Saechao’s KTA advisor to raise the price of their strawberries once the farm earned its organic certification.

Ryan Power, co-owner of New Family Farm, also in Sebastopol, became a KTA client in 2012, two years after starting the farm. He has since joined the KTA board, appropriately called the Kitchen Cabinet.

“The truth is that small-scale organic farming cannot be done without some kind of subsidy: social capital, or people being supportive, or a loan, or access to land,” said Power. Looking back, he realizes how fortunate he and his business partner, Adam Davidoff, were to find a landowner who would allow them to farm and live for free on the property for three years. “Otherwise I don’t think we could have met the challenge,” he posited.

Of all the organizations he’s worked with, Power told me, FEED Sonoma and KTA have changed their lives the most on the road to make farming viable. “They are doing the most to shape and support food systems into a resilient, diverse network of small farms,” he said.

Back at Stony Point, Koy Saecheo and her dad go back and forth about when he’ll be able to retire. They hope to pick up additional clients, increasing revenue, to make that possible.

For the KTA staff, who are adding new farms to the roster each year, the success of these farms is personal.

“I want to live in a world where people can grow food in harmony with their environment, take care of themselves and their employees, and make a living, such that they can send kids to college and save for retirement,” said Phinney.

I’d say this is not only an entirely reasonable goal, but a richly deserved outcome for those who do the critical and often hard work of growing our food.