Michael Pollan’s Challenge to Artisan Food Producers

NEVER LOSE SIGHT OF WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO DO THIS WORK

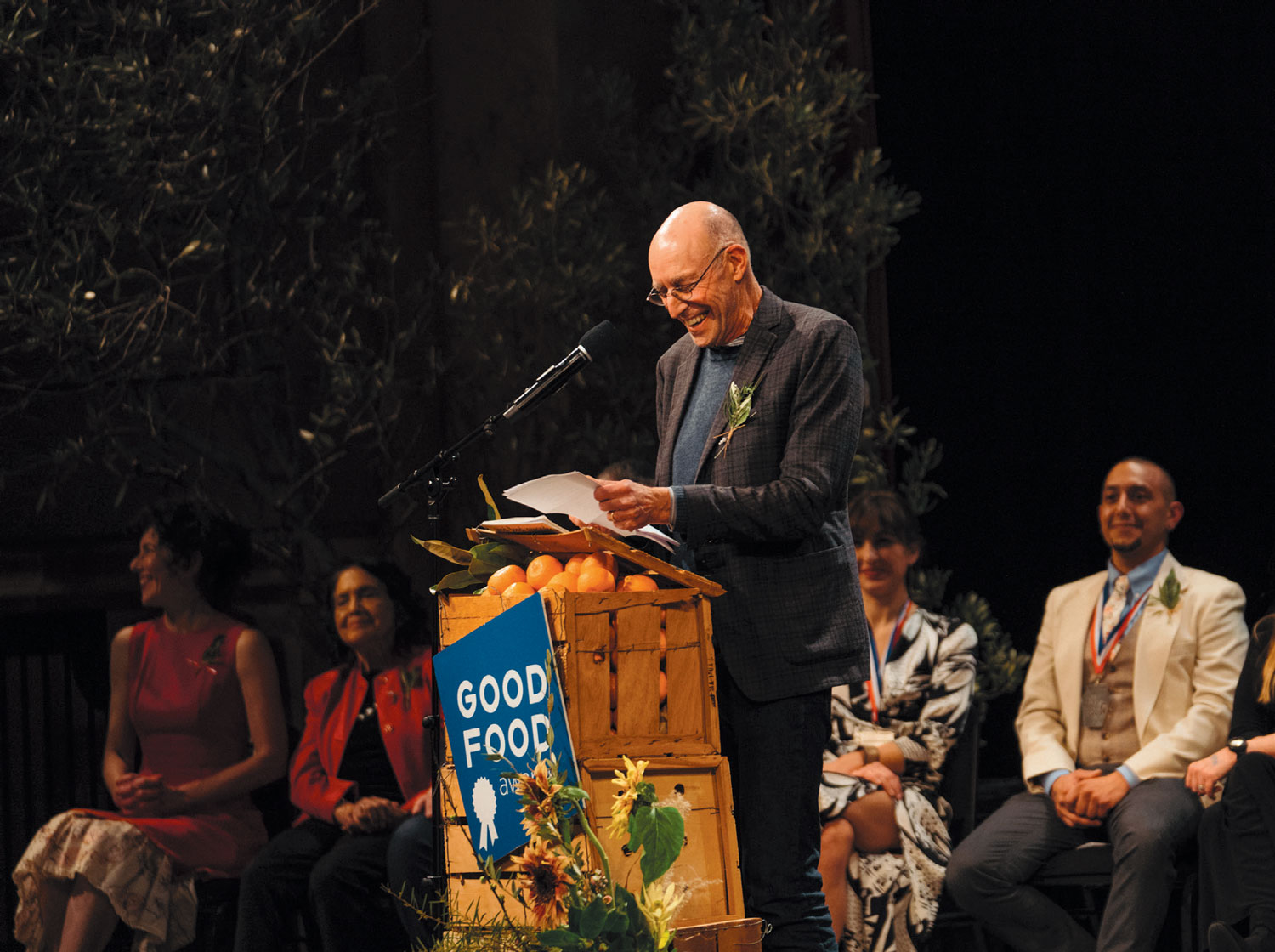

Editor’s note: Food system champion Michael Pollan’s keynote speech at the 10th annual Good Food Awards gala was at the same time cautionary and inspiring. His wise words are a call to action for us all: producer, press and consumer.

All I could think about as I listened was that I had to publish the speech in Edible Marin & Wine Country. So when I “happened” to run into him after the ceremony, I asked if he would allow me to do so. He reached into his pocket and handed it to me. I will be forever thankful for his generosity.

We are very mindful that since January 17, 2020, when this speech was given, the words “virus” and “infect” have taken on dire new significance throughout the world. We trust that our readers will read and understand these words in the context in which they were spoken.

Thank you, Alice [Waters]. And thank you, Good Food Award winners. It is an honor to share the stage with Dolores Huerta, a hero of the food movement.

To the winners: We’re here tonight to celebrate you and your work, but we are also here to celebrate a birthday—the 10th anniversary of the GFA—and, a birthday girl: Sarah Weiner, the visionary who has led this venture from the beginning.

This is my first time at this event, but I have followed the GFA from a distance since its second year, when I had the dubious honor of serving as a judge in the beer category.

This was an experience that goes under the heading, to paraphrase David Foster Wallace, of “a supposedly fun thing I will never do again.” Judging such a competition is far more grueling than I could have imagined, and the more so as the number of entries has burgeoned. My hat is off to the people with the stamina and discrimination to drink that much beer before noon without swallowing.

After 10 years the Good Food Awards have much to be proud of. Consider:

The awards have nurtured and helped grow what has become a critically influential corner of the food marketplace—generating more than $50 million in additional sales for both the food crafters and the sustainable farmers they support.

The number of such companies has grown exponentially in the last 10 years—judging by the number of entries: from 700 initially to 2,000 this year.

GFA winners have seen significant growth, and not only in sales: 10% report hiring new employees within months after their award.

The GFA are one reason why the community of mission-driven food and beverage companies is growing much faster than the food industry as a whole. And that is why I believe you have an outsized role to play in shaping of food in America. Especially at this point in the history of the food movement—the movement transforming the way we grow, produce and eat food in America—your work has become absolutely critical and central.

To understand why I think this is the case, let’s recall the origins of the GFA. As Sarah [Weiner] tells the story, the inspiration grew out of Slow Food Nation here in San Francisco in 2008. This was the first time that all of the various roots, shoots and branches of the artisan food community came together in what felt much like country fair on a national stage. The sense of community, solidarity and possibility were thrilling to everyone involved.

In retrospect, Slow Food Nation was a high water mark for the food movement. It was a gathering of a tribe that inspired all who took part in it. It was in 2008 that Merriam-Webster declared “locavore” to be the Word of the Year. For the first time, the City opened its arms wide to farmers and food crafters, artists and activists. The plaza in front of City Hall was transformed into a beautiful and bustling farm. [The documentary] Food Inc. was screened that weekend for the first time. And that fall a leading presidential candidate heard us, and was talking in Iowa about the need to transform American agriculture, to break its addiction to fossil fuel and put it back on a diet of sunlight. It was a heady moment.

Since then, things have gotten… well, more complicated. Soon after Slow Food Nation and the success of Food Inc., Big Food woke up to the threat to business as usual and began to fight back, spending tens of millions to organize industrial farmers against reform and to shift the narrative in the press. Change, we learned, doesn’t come easily and requires much more than telling a compelling story or electing a sympathetic President. (Although electing a sympathetic First Lady did do some good.) In the eight years of a sympathetic Democratic Administration, the Food Movement made a lot of friends in Washington, Alice [Waters] got her organic garden at the White House, Michelle [Obama] pushed through improvements in the school lunch program, but let’s face it—only “modest progress” was made in changing federal policy. We were outgunned.

But the hard work of building a movement goes on, much of it below the radar of the national media: Gardens get planted in school and communities. Food workers are organizing at every link in the food chain. Parents press to improve school lunch. Farmers organize to uphold organic standards and raise the bar with regenerative agriculture. Food studies programs proliferate on university campuses, as a new generation dedicates itself to the cause. The climate movement and the food movement have linked arms. Farmers and enlightened chefs are collaborating in innovative new ways, and the food movement itself is being democratized, putting social justice at the tip of its agenda, alongside environmental stewardship and public health.

And then there are you, members of the so-called “private sector”—a rather anemic term that is in your hands becoming something much more interesting. In the same way that separate roles of “consumer” and “citizen” are married when people make choices based not just on good value, but good values, companies too have the potential to confound the usual distinctions between private and public interest. Especially today, at a time when we can expect nothing from the federal government—indeed when the Administration is reversing progress on our issues, as it did today when it welcomed pizza and potatoes back into school lunch—it falls to companies fired by the kind of values these awards embody—for food that is good, clean and fair—to become a key driver of change. That’s you. That’s your opportunity and your responsibility.

So what do I mean by opportunity? The sector you represent may be small in terms of revenues, but it is tremendous in terms of influence. While Big Food’s share of the market is shrinking, your share, taken together, is growing— and Big Food knows this. Big Food has completely lost touch with the American consumer and they know that, too. Innovation in this industry no longer consists of dreaming up cool new products— unless you count brand extensions like an inside-out Oreo, or a taco made from a Dorito, as impressive contributions to our diet and culture. Now instead they watch little companies such as yours catch fire with eaters and then either rip them off or snap them up. That’s why big companies like Campbell’s and Mars and others have created giant investment funds to find the next Kind Bar or Honest Tea—and to find you. Companies like yours are now the leading edge of innovation in food.

What Big Food doesn’t understand, however, is that your success— the success we honor tonight—is about so much more than novelty or even flavor. Rather, it is about the deeper meaning embedded in the words “good food,” and the stories your products tell, indeed, about the very way you conceive of food. Which is not just as some edible material, some thing, but as the visible, taste-able and teachable manifestation of a set of relationships: between the maker and eater, between the eater and farmer, between the company and a community, and between all of these actors and the soil. To call such a food merely “a product” is to miss the whole point. In supporting your work with her dollars, the consumer is acting more like a citizen, casting a vote in support of a slightly different world. What you know—and they don’t—is how to earn that vote.

But what happens when Big Food snaps up the values-driven food company? One of two fates awaits. In the first, the product is shorn of the values it embodies and its story is hollowed out, if not falsified. We can all point to examples of companies to which this has happened.

Yet we can also point to counterexamples, where the values not only survived but went on to infect the parent company, fundamentally changing its DNA. This is the challenge we face when companies like yours—striving not to do business as usual, but business as social change— become part of Big Food: Will you be content to serve as an ornament, a nice but no longer necessarily true story about sustainability and community and social justice? Or will you be a virus, infecting the host with your values?

You all do beautiful work and would make a lovely ornament in the portfolio of any food corporation, but we hope for greater things from you. We hope and trust that your commitment to the values of this award—and to the full meaning of “good food”—never wavers and that, if and when you get big yourself or join forces with bigness, you never lose sight of what inspired you to do this work and that, always, you remain the virus.

So that is what I ask of you, indeed implore you: Go forth and infect!

Michael Pollan is the Lewis K. Chan Arts Lecturer and professor of the practice of nonfiction at Harvard University. Since 2003, Pollan has been the John S. and James L. Knight Professor of Journalism at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism. In addition to teaching, he lectures widely on food, agriculture, health and the environment and is the author of five New York Times bestselling books including 2006’s breakout The Omnivore’s Dilemma. He lives in the Bay Area with his wife, the painter Judith Belzer.

Calling All Good Food Artisans!

The entry period to submit your products for judging in this year’s Good Food Awards Blind Tasting is July 6–31, 2020!

The Good Food Foundation believes that it is more important than ever to recognize and celebrate the essential work that American makers are doing to provide the nation with tasty, authentic and responsibly made food and drink, and the Good Food Awards will go on!

Entries are welcomed in 17 categories, and from across the country. The catch: Everything must be produced with a commitment to environmental and social responsibility, supporting local economies and the planet.

The $78 entry fee offsets the cost of processing, sorting, storing and transporting entries. New and renewing members of the Good Food Guild receive one free entry, and a 2-for-1Early Bird discount with the code EARLYBIRD is available through July 8, 2020. Enter at GoodFoodFdn.org/awards. Deadline to enter is July 31.