Red Seaweed & Green Cows

How Algae Could Become a Climate Game Changer on the Farm

Could seaweed help solve the serious methane gas pollution problem posed by bovine belches? Straus Family Creamery thinks so. On the strength of a small trial that garnered large results, the Petaluma-based dairy business has partnered with Hawaii seaweed-supplement producer Blue Ocean Barns to serve seaweed on the farm as a way to combat the “carbon hoofprint” of cows.

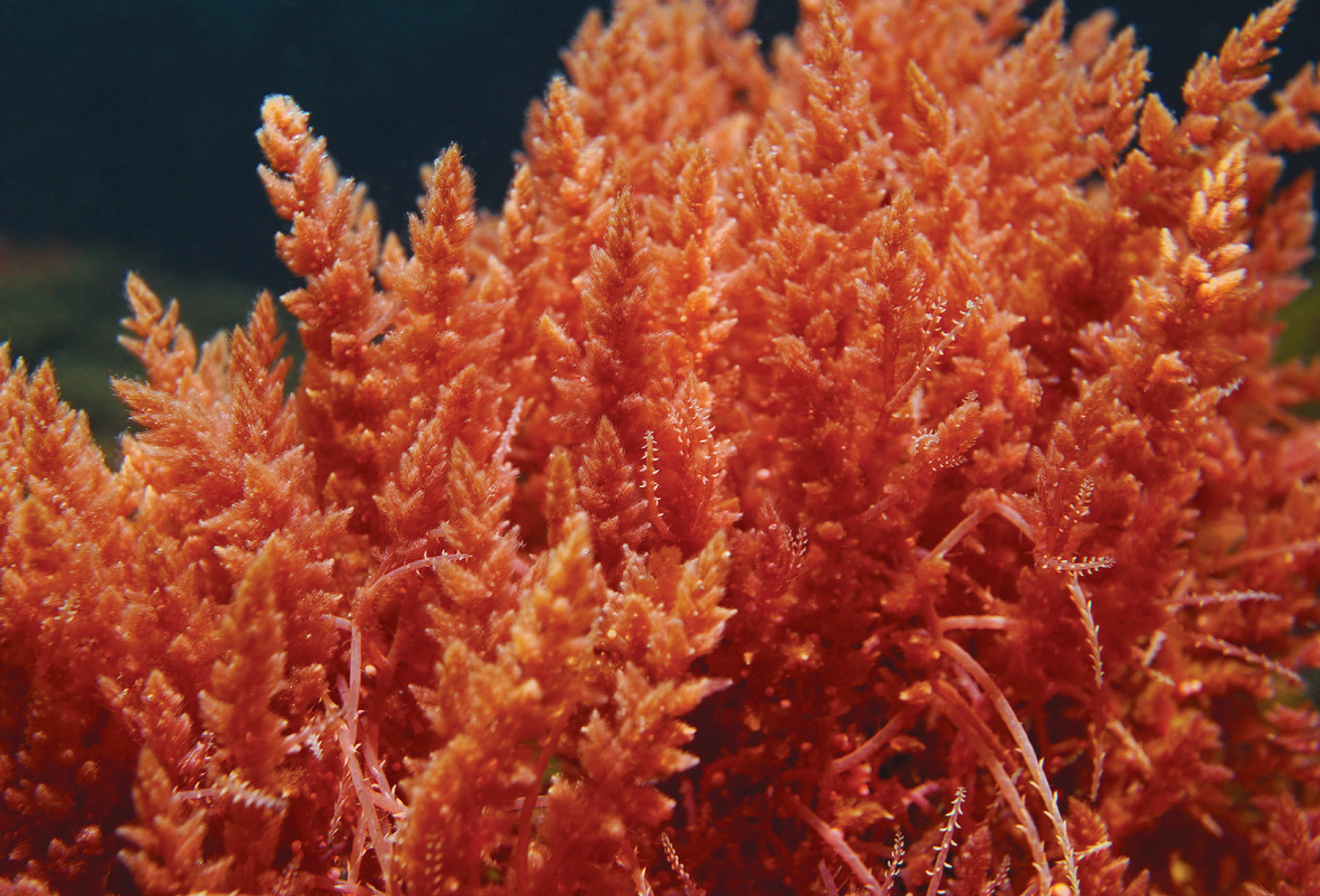

In the first commercial trial of its kind in this country, 24 dairy cows on Straus’s organic dairy farm in Marin were fed a sprinkling of seaweed powder made from a specific red seaweed (formally known as Asparagopsis taxiformis). It reduced the animals’ enteric methane gas emissions (aka cow burps) by an average of 52%, and as much as 90%. Straus received approval from the California Department of Food and Agriculture and a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Organic Program variance to test the supplement in a six-week experiment.

This feathery red warm-water seaweed grows wild in subtropical locations such as Australia and the Azores. Earlier research had found that it is the most effective type of seaweed for reducing methane output. The hope is that if the algae can be cultivated, commercialized and produced on a large scale, it could transform dairy and beef cattle farming into a more climate-friendly industry.

“This is a huge leap forward for us in creating a sustainable farming system that is beneficial to the planet and our communities,” says farmer Albert Straus, founder and CEO of Straus Family Creamery. “Red seaweed is also the next critical step we need to reach our carbon- neutral farming model goal in 2023 on the Straus Dairy Farm.”

Seaweed is salty and slimy, but the dried powder had no impact on milk production, taste, texture, smell or color. That’s important to farmers and consumers: Straus knew that any changes in flavor or form wouldn’t fly.

The trial, says Straus, confirmed on a real-world dairy farm what previous studies had suggested in a closely controlled university setting. The methane released by the cows was tallied several times a day using a GreenFeed, a breathalyzer-like machine that measures emissions from belches. Straus set out to discover the impact of adding about ¼ of a pound of red seaweed each day to his cows’ regular 45-pound diet in August and September 2021. (In California, dairy cows typically receive more grain-based feed during the summer months, when fresh grasses—a cow herds’ primary seasonal food source—die off and are not as readily available for animals on pasture).

Straus intends to use the seaweed on all 12 farms that supply the creamery—just as soon as it’s approved by the USDA. Straus hopes that will happen in the summer or fall of 2022. He says the additional cost of the additive, which will likely be produced in a pellet or powder form, is negligible. “Some animals liked the taste more than others in the trial,” he notes, which helps explain the range in results. But in the future Straus says the additive will be included in a vitamin-mineral supplement, rendering it undetectable when evenly mixed into animals’ feed.

Why Cows’ Methane Output Matters

Methane is a short-lived but potent greenhouse gas, and greenhouse gases are a major cause of climate change, second only to carbon dioxide. Methane is anywhere from 25% to 80% as potent as carbon dioxide in warming the atmosphere, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Environmental Defense Fund, although it breaks down more quickly.

Bottom line: Bovine burps aren’t environmentally friendly. Agriculture accounts for about 10% of greenhouse gases in the U.S., according to the USDA. Much of it of comes from cows—there are about 100 million in the States—that routinely belch methane as they digest bulky forage such as grass, alfalfa and hay. This natural process is responsible for more methane than any other source— around 27.1% of total emissions in the U.S., according to a 2021 EPA report.

It follows that California, which has the most dairy cows of any U.S. state and is the nation’s top milk producer, is also responsible for the most dairy farm methane emissions in the country. Under a landmark law passed in 2006, the Golden State must reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an ambitious 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 to meet its climate goals. In 2016, the state passed separate legislation to reduce methane and other short-lived climate pollutants by 40%, adding additional urgency for dairy farmers and cattle ranchers to address global warming concerns.

The world’s 1.5 billion bovines contribute about 14.5% of greenhouse gas emissions, according to Ermias Kebreab, a professor and associate dean for global engagement in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences at the University of California, Davis. Kebreab studies seaweed’s—and other ingredients’—impact on cow emissions. If all the world’s cows formed a country, they would be the globe’s third-largest greenhouse-gas emitter, behind China and the U.S. and ahead of India, noted Bill Gates in a blog post. The typical dairy cow belches around 380 pounds of harmful methane a year, according to one bovine belch researcher.

At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland, over 100 countries, including the U.S., agreed to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030. Converting cows to carbon-neutral milk producers is an idea whose time has come.

Cows have an intricate digestive system. Enteric fermentation— the process of converting complex sugars into simple molecules for absorption, produces methane as a metabolic byproduct, explains Kebreab. Cows have multi-chambered stomachs. Their rumen, which serves as a storage and fermentation vat, contains microbes that ferment feed and break it down into nutrients. The process also generates chemical compounds—such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen—that the cow’s body does not take up. Methane-producing microbes use these compounds to form methane, which the cow’s body expels from either end. A note on that: The idea that cow flatulence is a major climate change culprit is a common misconception. It’s bovine belches that do the most damage to the planet: accounting for 95% to 98% of the methane released by cows, according to Breanna Roque, an animal science researcher, now based in Queensland, Australia, who consulted on the Straus trial while a PhD student at UC Davis.

Seaweed is also a complex living organism. Turns out that algae have active ingredients—including a compound called bromoform—that can inhibit a cow’s digestive system from converting certain enzymes into methane, instead releasing them as hydrogen. Holy cow: That’s a major win for the environment, as far as scientists and farmers are concerned.

Out of the Blue: A Potential Solution

Enter the seaweed evangelists. “Red seaweed immediately and radically drops enteric methane emissions—and an immediate and radical solution is what the planet needs right now,” says Joan Salwen, co-founder and CEO of Blue Ocean Barns, headquartered in Kailua-Kona on Hawaii’s Big Island. Since there isn’t enough wild red seaweed available to harvest for broad use, seaweed farming startups, including Symbrosia, also based in Kailua- Kona, are trying to fill the void. In Australia, FutureFeed, a partnership between the Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organisation, Meat and Livestock Australia and James Cook University, is working on producing commercial quantities of the seaweed supplement for cows at dairy farms and beef feedlots around the world. For research purposes, the red seaweed in studies has been hand harvested—often from far-flung locations, making it an expensive proposition—which is why companies like Blue Ocean Barns and FutureFeed are embarking on producing the product on a mass scale closer to dairy farms and cattle ranches.

Blue Ocean Barns expects to be selling its product commercially by the fall of 2022, with the goal of ramping up to help farmers and food producers reach those 2030 emission reduction targets. Salwen—who was born into a farm family in Iowa—says several large companies are slated to be its first customers. At press time, though, the startup was finalizing details of the partnerships and she declined to reveal if they were dairy or beef farms or food businesses, or where in the country the companies are located. Twenty of the largest dairy and beef producers in the world release more greenhouse gas emissions than Britain, France or Germany, according to a 2021 report by Meat Atlas, published by European environmental advocacy organizations. The five biggest meat and milk producers in the world emit the same volume of greenhouse gases as oil giants like Shell or Exxon, according to the report.

In Marin County’s Albert Straus, Salwen sees a kindred spirit and fellow environmental steward. But she’s also determined to see this innovation have an impact beyond one organic dairy producer in Marin.

“Corporations are the catalyst for bringing this innovation to scale—the enlightened among them, who are really serious about pulling greenhouse gas emissions out of their supply chain,” says Salwen. “It’s simply not enough to have solar panels on roofs or drive an electric fleet. Companies know they need to do more.” Blue Ocean Barns has drawn corporate investment from the likes of dairy industry agriculture cooperative Land o’ Lakes and confectionary company Mars Wrigley, which awarded the startup $200,000 in 2019 as part of a pitch event for sustainability innovations.

Salwen helped raise the funds for the Straus trial. She secured around $1 million for the study from foundations including the Schmidt Family Foundation, the David & Lucile Packard Foundation, and Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research. It was not hard, she says, to find philanthropists eager to support climate change innovations. Funding for the $7.5 million startup has come from venture capital concerns, including Valor Siren Ventures, a food- and technology-focused fund underwritten by Starbucks.

Blue Ocean Barns is the result of what Salwen calls her grownup gap year at Stanford University, where she steeped herself in ideas and innovations around how farming and food systems can be improved both to feed a growing world and to protect a fragile planet. In a previous life, Salwen served as a business strategist for corporate giant Accenture; she also helped found and served as head of school at the private Atlanta Girls’ School. Familiar with Straus products from Stanford’s dining centers, Salwen met Albert Straus on the grounds of the university and they haven’t stopped talking seaweed since.

Blue Ocean Barns grows seaweed in vertical tanks on land, using pumped-in seawater that provides the nutrients the red algae need to thrive. Research into the best way to cultivate the seaweed is ongoing, including at a satellite location in San Diego. It’s expected that just an ounce or two of the powder per cow per day should be enough to make a difference. As for who would absorb the cost of the supplement along the food supply chain—farmers have notoriously thin profit margins—Salwen wonders whether big food corporations— who have their own emission reduction targets—would be willing to absorb the cost of the additive by paying more for milk to support such climate-friendly innovations.

Incentives such as government subsidies for farmers or carbon credit offsets could make the innovation more palatable to producers. Consumer demand for food that doesn’t contribute to climate change could also be a factor here: Would milk drinkers and steak eaters pay more for a product that doesn’t contribute to global warming?

Researchers Test Ways to Minimize Methane

The Straus study is not the first conducted on seaweed and cows. According to FutureFeed, it was Canadian farmer Joe Dorgan who first got wind of the beneficial impacts of seaweed on coastal cows. To his surprise he discovered algae improved milk production, and, quite unexpectedly, it made cows less gassy. Scientists in Australia, intrigued by the discovery, started testing more than 30 kinds of seaweed for their methane-busting benefits. Red algae proved the best at mitigating methane emissions.

In a 2019 study, UC Davis’s Kebreab and Roque reduced methane emissions from cows by up to 67% by supplementing their feed with 10 ounces of seaweed for two weeks. But in that study the cattle that ate this relatively large amount of seaweed also consumed less feed, which reduced milk production, a major drawback for dairy farmers. Kebreab, Roque and other scientists followed that research with a study in 2021 that found seaweed in feed reduced the emissions of 21 beef cattle by as much as 82%. The 147-day study, supported by Blue Ocean Barns but independently carried out by UC Davis, also found that the seaweed additive reduced farmers’ feed requirements by 14% with no change in steer weight gain during the five-month-long investigation. The thinking is that a percentage of the animal’s energy from feed is lost as methane emissions. The ocean addition didn’t impact the tenderness, juiciness or flavor of the animal’s meat, researchers found in a blind taste test following the experiment. “These are significant and surprising results,” says Kebreab, who is also a scientific advisor to Blue Ocean Barns.

“These kind of substantial emission reductions could help California dairy farmers and cattle ranchers meet new methane emission standards and sustainably produce food we need to feed the world.” Kebreab’s lab has also experimented to see the effect of different plant options—including oregano, garlic and lemongrass— on cow burps. To date, seaweed sets the gold standard for reducing emissions.

Replicating these results on a working farm—where cows have more control over what they eat—is more challenging, says Roque, who now works as a research scientist at FutureFeed. The challenge of how to ensure grazing cows consume the seaweed supplement is an open one. Feeding cows seaweed is most practical in feedlots. But in the case of beef cattle, they only spend the last few months of their short lives there, which would account for just a small portion of their lifetime methane output. Beef cattle would be free to belch away while grazing on pasture, where it’s much less practical to sneak seaweed into the diet.

Roque says more seaweed study is needed to fully understand its value. For example: “Can we show that dairy cows eating Asparagopsis reduce methane emissions throughout at least a full lactation cycle and beyond?” she asks on the radio program Science Friday in a 2021 segment.

“Feed is typically the number one cost for livestock producers and can reach up to 60% of total on farm costs,” says Roque. If Asparagopsis can alleviate some of this cost for producers and reduce greenhouse gas contributions it provides an additional incentive for farmers wanting to improve their environmental footprint.”

Seaweed Skeptics and Algae Advocates

Albert Straus has a long history of introducing agriculture-based solutions to climate change challenges on his farm by prioritizing sustainable organic farming practices. A methane digester takes manure from cows and captures methane and converts it into electricity for the farm. Together, seaweed and the digester could reduce methane emissions by 90%, Straus says, helping him meet his goal of creating a net carbon neutral dairy farm by next year. The dairy also has a carbon farm plan, which includes using compost and animals grazing, to help sequester or return carbon back into the soil from the atmosphere. And the dairy has converted all its vehicles on the farm to electric: The truck used to feed the cows is electric and powered by the cows that it feeds, Straus likes to point out. [Editor’s note: For more information on Straus’s methane digester, see the Summer 2016 issue of Edible Marin & Wine Country; for more on carbon sequestration, see the Fall 2015 issue.]

There is support for a seaweed solution in other quarters. Some question, though, whether companies can cultivate enough to meet demand. Luke Gardner, an aquaculture specialist with California Seagrant based at the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, a facility run by San Jose State University, remains doubtful that commercial entities can produce enough algae to make it cost effective for widespread use. Gardner, who is also a small-scale cattle rancher, is in the process of researching native California seaweed with similar properties, though he says he hasn’t found a seaweed to replicate the results of red algae. “I’m focused on the science side of the seaweed solution; I’m not selling a product. I’d like to see more research.”

Jen Smith, a professor of marine ecology and conservation at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, studies red seaweeds native to the state. “If we’re going to use seaweed to feed cows and do it on an impactful scale, there’s an interest in local sources, so we’re not sticking it on a boat, burning a bunch of fuel and bringing it to California,” says Smith, who is also a scientific advisor to Blue Ocean Barns. “We’re interested in growing it here.”

And there are those who believe that the best way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from farm animals is to simply follow a plant-based diet and reduce or eliminate meat or dairy consumption. Pastureland and crop production for livestock use up 77% of the planet’s farmed land, but livestock produces less than 20% of global calories. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations’ premier climate body, recommends that humans consume less meat and dairy as a way to reduce global warming.

Kebreab, who grew up in Eritrea in northeast Africa, maintains that only a small fraction of the earth is suitable for crop production and that much more land is only useful for grazing, so livestock continues to play a vital role in feeding billions of people on the planet, particularly residents of less-resourced countries, something he has witnessed firsthand in a country that experiences severe droughts and famines.

Salwen doesn’t sweat the naysayers. “There’s no question that Asparagopsis can play a huge role in reducing methane emissions,” she says. “One of the things that is so beautiful about this additive is that it works in the cow the day she eats it. That’s exciting because a lot of the things that are going to need to be done to reduce methane emissions are going to take a lot of time.”

“Farmers can play a big role and cows can be an important part of the solution to climate change. We can scale this over a very small geographic footprint and create a very high yield per acre of this plant to feed all the cows and cattle in the U.S.,” she says. “It’s tangible, within reach, and something we can do within this decade.”