Revitalizing Native Foodways and Food Sovereignty in the North Bay

ANYONE WHO HAS spent time hiking, exploring or just passing through Northern California is familiar with its iconic hills dotted with groves of ancient oak and bay trees. These vistas provide a glimpse of how our region might have looked long ago—before freeways cut through the rolling hills, before tracts of houses were built, before cities were developed, before Europeans occupied the land of the original Indigenous peoples. These resilient and mighty trees provide a stunning visual backdrop for us all, but for the Native Miwok and Pomo of our region they represent much more: a connection to the earth, a link to tradition and a fundamental source of nourishment.

Acorns from these oaks were once so essential that they made up 50% of the Native peoples’ diet. The region’s woodlands were also rich with bay nuts, buckeyes, manzanita berries, blackberries, wild mushrooms and wild greens. Deer, bear, elk and quail roamed the forests, and the waterways teemed with salmon, trout and shellfish, as well as being a source of salt and seaweed. Self-sufficient Indigenous communities tended, gathered and hunted using sustainable and ecologically sound practices, steeped in tradition informed by ancient wisdom.

While wild food is still plentiful in some areas of our region, access is often difficult and Native peoples’ diets are no longer what they used to be. Since the arrival of Europeans, and continuing through current times, Native ways of life—including traditional foodways—have been persistently disrupted to the point of decimation. Ties to ancestral stories, ecological knowledge and practices related to land and food have been interrupted due to forced assimilation and land loss. Largely as a result of these factors, today’s Native communities suffer from high rates of obesity and diabetes, while at the same time they struggle with hunger and food insecurity.

Despite the profound challenges facing their communities, two Native-led groups in the North Bay are finding innovative ways to restore and promote Native foodways and food sovereignty.

CALIFORNIA INDIAN MUSEUM AND CULTURAL CENTER

“Food sovereignty is the right of people to define and reclaim what food is in their community,” says Nicole Lim (Pomo), executive director of the California Indian Museum and Cultural Center (CIMCC) in Santa Rosa. CIMCC educates the public about the history, culture and contemporary life of California Indians through its exhibits, which portray these subjects from a Native perspective. Additional programs serve to preserve and protect Native culture and traditions and provide job training and education.

CIMCC’s service-learning group, Native Youth Ambassadors (NYA), is made up of Pomo and Miwok youth working to strengthen their tribal identity and cultural knowledge. Since the group began in 2010, NYA projects have included the development of a Pomo language app and documenting cultural education. In recent years, they have turned their attention to the issue of food sovereignty.

The focus on food is an obvious one for Lim, who echoes local tribal community member Meyo Marufo’s powerful sentiment, “Kill the food, kill the culture.” Lim’s goals with this work are to build up access, skills and knowledge base within Native communities, and also to educate the public at large. “We hope people will engage in allyship that supports our efforts.”

ACORN BITES

In 2016, NYA embarked upon an extensive research project to assess Native communities’ access to healthy food, familiarity with traditional foods and cultural knowledge around foodways. The findings showed that while most tribal community members have a strong interest in healthy traditional foods, there are many obstacles to obtaining them, including lack of ancestral knowledge, cost and difficulty in accessing the land on which it grows.

One very bright idea that came out of their research was the production of what the group named Acorn Bites, a nutritious snack bar made from local acorn flour. Guided by tribal elders and cultural educators, the youth have learned traditional methods—as well as cultural protocols—for harvesting and processing acorns. Due to their high levels of tannins “acorns often have a bad rap, but we were pleasantly surprised,” says Lim. When they are properly soaked, leeched of their tannins, dried and ground, acorns have a nutty, earthy flavor. Plus, acorns are high in fiber; protein; vitamins C, A and E; calcium; potassium and antioxidants. Most notably, they are low on the glycemic index and may help reduce blood sugar and potentially thwart diabetes.

NYA members are active in the entire process of producing Acorn Bites, from collecting and processing acorns to making and selling Acorn Bites, which they do through Native networks and at local farmers’ markets. The primary barrier the group faces as they strive to increase production is sourcing enough acorns to make the acorn flour. By developing partnerships with local municipalities and landowners, as well as advocating for legislation, they are working to expand access for their community to their own ancestral lands and this vital food source.

The Acorn Bites project serves many purposes all in one small but mighty bite: It works to restore preference for traditional foods, preserves cultural knowledge and creates a modern and accessible connection to the ancient and highly nutritious acorn. The focus on food sovereignty has been powerful. “We’ve learned a lot about how we heal ourselves and our community,” says Lim.

THE CULTURAL CONSERVANCY

The San Francisco–based Native-led nonprofit The Cultural Conservancy also works to protect and restore Native lands and cultures. The organization started 35 years ago in Marin County, focusing on the protection and conservation of sacred lands. Today, the organization works primarily to revitalize and preserve Indigenous lands and cultures through Native foods and land revitalization. Melissa Nelson, the organization’s president and CEO, believes that there is a “critical need to uplift Indigenous peoples in this era,” because, in her mind, many of the problems facing our modern world can be solved by looking to traditional ecological knowledge and land-based practices. Nelson, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, says much of the conservancy’s work is focused on foodways because “food is the best connector between nature and culture.”

The Cultural Conservancy co-stewards an organic farm; produces workshops with Indigenous chefs, nutritionists, Indigenous knowledge holders and organic farmers; and maintains a Native seed library. The organization produces Native media and hosts a thought-provoking podcast, The Native Seed Pod.

Since 2014, they have also distributed fresh produce to Native communities in the Bay Area through a network of “hubs,” primarily urban Indian community centers and health centers. The produce is donated by partner farms like the San Francisco Zen Center’s Green Gulch Farm in Marin, as well as being grown on the College of Marin’s Indian Valley Organic Farm & Garden (IVOFG).

FROM THE GROUND UP

IVOFG was founded in 2009 by a collaboration including College of Marin, Conservation Corps North Bay, UCCE Marin Master Gardeners, Marin Community Foundation and the Marin County Board of Supervisors. Today, the farm is managed by the College of Marin, with support from operational partners UCCE Master Gardeners and The Cultural Conservancy.

“From the start, the founders of the [IVOFG] farm wanted to recognize the First Peoples of this space,” recounts Sara Moncada (Yaqui), who serves as The Cultural Conservancy’s chief program officer. Local Native elders and leaders were invited to be a part of the process, and in 2012 hosted their first ceremonial planting. Since becoming involved in IVOFG, The Cultural Conservancy has deepened that connection. They’ve incorporated a Three Sisters Foodways Garden featuring “culturally significant, heirloom varieties” of corn, beans and squash that grow symbiotically. “The Three Sisters are a perfect example of a traditional story that is actually ecological science,” explains Melissa Nelson. In late summer, Scarlet Runner beans add nitrogen to the soil as they wind their way up supportive stalks of Seneca white corn, all encircled by Blue Hubbard squash, whose spiky vines help deter pests from all three plants. An Ethnobotany Teaching Garden highlights local plants used for traditional arts, crafts, medicines and teas. Moncada says that a grove of “tended” oak trees, whose acorns can be harvested, is in the works.

THE PANDEMIC SHIFT

Bay Area Native communities, like other minority groups nationwide, are being disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Like so many organizations and businesses, CIMCC and The Cultural Conservancy have both had to reassess and pivot to best respond to the immediate needs of those they serve. For CIMCC, that has meant putting on hold all in-person activities, ceasing the production of Acorn Bites, closing their doors to the public (before reopening and closing again) and shifting energy and resources to pandemic-related response. Along with their funders and partners, CIMCC is helping tribal community members in need with emergency assistance for utilities, medical supplies, diapers and more. These items are distributed three times per week, along with boxes of locally grown fruits and vegetables provided by The Cultural Conservancy. The demand for fresh, healthy food is greater than ever.

Similarly, The Cultural Conservancy has had to cancel all of their events and workshops (including their annual harvest celebration and feast), and must make do without their usual constant flow of community volunteers. In fact, during the recent harvest season, Nelson and her executive team frequently canceled their weekly meeting in order to join the harvest crew at the IVOFG. Similarly to most nonprofit organizations, the uncertainty around future funding sources given the unstable economy is scary. “We’re nervous, but we will still grow food and feed people,” The Cultural Conservancy’s Moncada says with a smile.

FUTURE OF FOODWAYS

Despite the climate of uncertainty, the future looks bright for Native foodways in the North Bay. CIMCC is developing new virtual cooking classes, cultural workshops and curriculum for schools. They are also constructing acorn leaching stations where community members will be able to process acorn flour for their own use.

The Cultural Conservancy is beginning to develop a new 7.8- acre farm north of Sebastopol, which they recently purchased. Using what they have learned at IVOFG, “Heron Shadow” will be a space to further their work on a grander and deeper scale. Plans include a farm stand, value-added products, an expanded CSA program, restaurant sales and distribution of food to a wider network of Native communities throughout the Bay Area. While increased food production may be a driver of the new project, Moncada and Nelson are clearly most passionate about the opportunity to provide critical access to land for disenfranchised Native communities, allowing for a safe place to connect with the earth, “to sit under that oak tree and re-root to that ground.”

Indigenous groups, the Bay Area community at large and the planet all stand to benefit greatly from this critical work. Melissa Nelson is hopeful for the future: “So many young people are passionate about tending the land and growing their food, and about the health and well-being of our community and the earth. It’s just very inspiring.”

California Indian Museum and Cultural Center: Cimcc.org The Cultural Conservancy: NativeLand.org

NATIVE FOODS GO MAINSTREAM

In the food-centric Bay Area, young chefs are forging new paths to preserve ancient ways. Chef Crystal Wahpepah is an Indigenous (Kickapoo) chef whose catering company serves authentic Native cuisine. Her appearance on the Food Network’s wildly popular show “Chopped” put Indigenous cooking on a national stage. WahpepahsKitchen.com

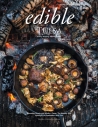

Vincent Medina and Louis Trevino’s Café Ohlone popup at University Press Books in Berkeley created a space for, in their words, “boundary-breaking conversations over seasonal Ohlone cuisine.” Their offerings included acorn bread, soft-boiled quail eggs and venison wild mushroom stew. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the pair was forced to close their physical space, but at press time Medina and Trevino were exploring other ways to allow people to experience traditional Ohlone food and culture. Follow them at @makamham.