Wine Country on Lockdown

WHAT TO DO WHEN YOUR INDUSTRY’S RAISON D’ETRE IS PROHIBITED? FIGHT LIKE HELL

The members of the Wine Country Coalition for Safe Reopening, an advocacy group launched in the fall of 2020 with members from Marin, Napa, Sonoma and Mendocino counties, and elsewhere, were fed up. After nearly a year of state prohibitions on outdoor dining and a steady drumbeat of misinformation about the safety of restaurant and catering operations, their hospitality-based businesses were on life support. Known for accommodating the needs of their guests in the most gracious of manners, in this instance they were not going to just grin and bear it.

The group took to the courts, filing case number 21CV000065 in Napa Superior Court on January 19, 2021, challenging Governor Gavin Newsom’s repetitive bans on outdoor dining and wine tasting as “arbitrary, irrational and unfair…. with no scientific basis.”

Steered by Cynthia Ariosta, operating partner of St. Helena’s Pizzeria Tra Vigne, and Carl Dene, owner of Brannan Cottage Inn in Calistoga, the Coalition was fighting for the very life of their decimated industry. The group got its start when Ariosta, after riding the rollercoaster of public safety mandates since March 2020, spent additional precious capital to comply with ever-changing guidelines and then was told by the state—yet again—that restaurants, despite adhering to the health mandates as set forth by the CDC and the State of California to operate safely, must close during the busiest time of the year: the fall and winter holidays.

“The guidelines were never good enough,” Ariosta said. “We were laying off employees, bringing them back, then cutting them again. We needed to get local officials involved.” But there was not much the local mayors and regional supervisors could do to counter the closures—counties could be more aggressive in restrictions, but could not reopen before the Governor said so.

Mayors and supervisors also do not have the power to adjust property taxes or create other financial cushions to aid an industry. As a group and a region in crisis, the Coalition, with local political leaders offering their support, needed to aim higher.

MEDIA ATTENTION AND A LAWSUIT BRING CHANGE

With funds raised from among the 50-plus members of the Coalition and a GoFundMe campaign, the Coalition hired lawyers and a public relations team to help get the word out about their plight. The campaign was instantly successful, garnering stories in the San Francisco Chronicle and LA Times and television news stations across the state. Nationally, CNN picked up the story, and Fox ran segments across its programming.

“It hit a nerve,” said Ariosta. “We were operating under CDC guidelines. Why are we any less safe than Costco?”

The lawsuit demanded a restoration of outdoor dining and wine tasting, asserting the violation of equal protection and due process clauses under the U.S. Constitution. It also asked for declaratory relief arguing that these businesses were tasked with making their places of business safe, following government rules, without being compensated the fair market value for the property rights that were being taken away.

Outdoor dining in Northern California was re-re-opened just days after the lawsuit was filed.

So then what? According to Ariosta, the lawsuit is on hold, ready to be revived in the event the state re-imposes restrictions. The Coalition’s membership, satisfied for now that the reopening is good enough, is in wait-and-see mode. “We could move forward for damages or dismiss ‘with prejudice,’ so the lawsuit still stands,” Ariosta said. “If bans happen again, we would reenact the lawsuit.” The lawsuit, more than anything else, forced the change that Wine Country’s hospitality industry needed, desperately.

“We don’t want to refile to sue the Governor,” Ariosta says. “We do want to be able to run our businesses and do what was originally asked of us. I put up an $18,000 tent in November— some of our member venues had huge capital outlays that cannot be monetized at all—then we were told we could not use these investments in December. We need guidance we can count on. And there needs to be some accommodation from government to alleviate our financial burden—a reduction in fees or taxes, like alleviating the Department of Health Fees and ABV fees, if they are going to limit our ability to function. This cannot go on for another year.”

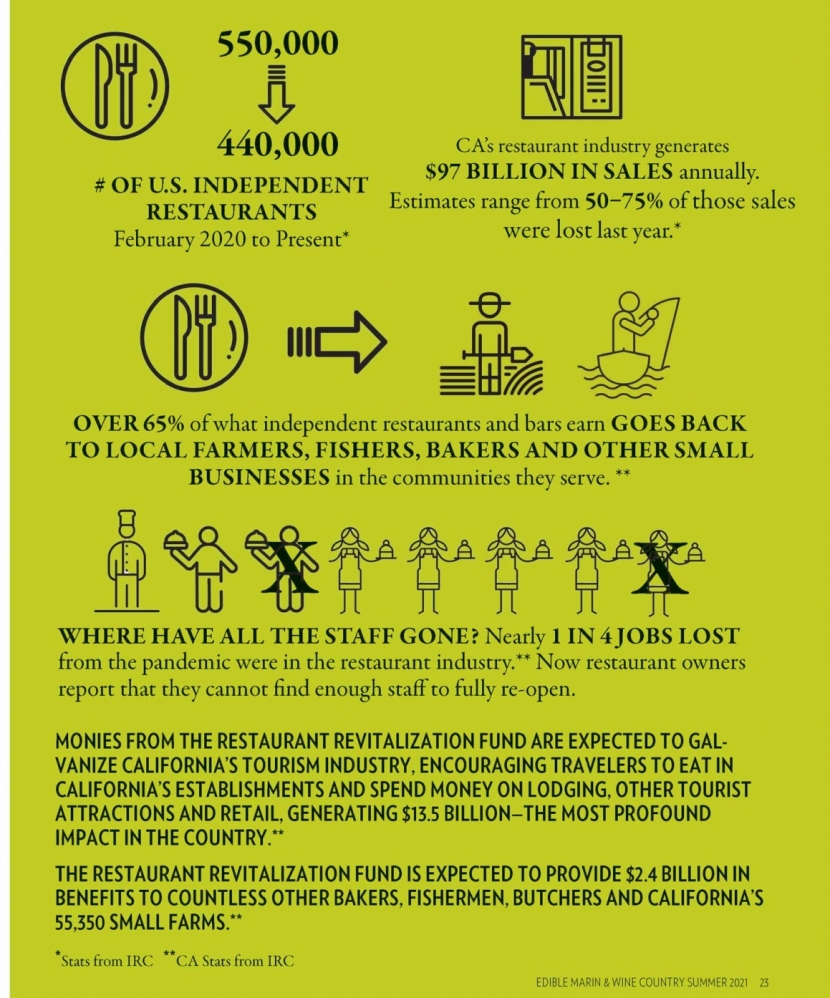

The damage is already immense. As quoted in the lawsuit (page 15, section 62): For Coalition members, ‘restaurant sales are down up to 75% as a result of Defendants’ ban on outdoor dining.’ That loss in revenue, in turn, has resulted in a 50–70% or more reduction in hours and staffing.

ADDITIONAL BURDENS PLACED ON EVENT BUSINESSES

Julia Kendrick Conway, who owns the Mendocino-based catering company Assaggiare Mendocino, lost all of her business last year, including destination weddings, corporate retreats and events for the wine industry. Her business is a part of two new groups that formed last summer when it became apparent that shutdowns would last longer than 90 days: the California Association for Private Events (CAPE) and the California Events Coalition (CEC). CAPE is for businesses that work events with closed guest lists, like bar mitzvahs, while CEC is the semi-official arm of the Live Events Coalition and has been lobbying nationally for relief. “No one thinks about the roadies, riggers, caterers and all the people who put on events of all sizes,” Conway said.

Like other industry professionals, Conway notes that the state already heavily mandates the safety procedures—from alcohol service to infection control—of her industry, yet the state’s repeated closures failed to recognize the industry’s preexisting skill set. CAPE and CEC organizers are working on two fronts—helping to develop new COVID-safe rules, and making sure the legislature recognizes the economic damage wrought from keeping an industry closed. They are looking at how to limit people’s natural desire to congregate around a bar at a wedding, for example, and how to make dancing safe. Self-service buffets may be a thing of the past, but tables dancing as a group in pre-designated areas may be an acceptable part of future, COVID-safe, weddings of all sizes.

With additional COVID safety plans already mandated by CalOSHA specific to individual event sites, Conway is facing a more complicated working environment. “I work in 15 to 20 locations in Mendocino and Sonoma, and need a general plan, plus specific plans for each site,” she said. “That could mean I’m required to remove all the chairs from a location, while at another venue there is a separate service that comes in the next day to clean up.” Conway added: “Photographers and DJs will now need a written COVID safety plan, with additional liability coverage.” At the same time, private insurance is pulling back and removing coverage for communicable diseases.” It has meant a beefing up of contracts and further industry uncertainty.

Collecting signed COVID plans from contractors and other workers before each event will increase the burden on small businesses and independent operators alike, and meeting the standard set by the state will be challenging. Conway spoke of the chain of events cascading this way: “If someone wants to report an event where no one is masked, they can call the sheriff. The sheriff might tell them ‘we don’t have bandwidth’ and refer them to County Code Enforcement, which is not open on weekends. Code Enforcement then goes to the Board of Supervisors. No one is enforcing it. No one is winning.”

Conway expects more than half of the vendors she did business with as recently as 2019 to find the new regulations too onerous to continue. That pressure translates to opportunity for some, but, like Ariosta, she would like to see some mitigations put in place by the state that would enable small businesses and individuals to continue to operate. “COVID has brought the industry together,” Conway said, “it’s broken down some barriers and given us a common cause to rally around.” But the restaurant and events industries need a more organic route to let the Legislature know this economic sector is dying. “Destination tourism is a big part of the draw of California. We need a big push coming from the tourism sector supporting our industry.”

CANCELING UNCERTAINTY

Conway says 2022 is already almost fully booked for weddings, driven by couples who had to postpone their big day from 2020 or 2021. How will she and other event planners, caterers and venues meet the demand? Conway used some of her Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans to continue to pay her staff for sitting at home in her mostly rural county. “It’s the only way I’ll have a staff when this is over. My employees make this company what it is,” she said.

With vaccinations happening at a good clip in California, Conway hopes to resume her business at 50% capacity by July of this year. But most weddings do not get planned in a day, or a month. With event lead times of up to three years, Conway’s current client contract includes a clause through which clients agree to abide by whatever county and state restrictions are in place on their event date. “It is the only way I can book something going forward,” she said. “Love can’t be canceled. We want to cancel the uncertainty and fear.” Though she is amazed her business survived at all, Conway remains cautiously optimistic for fall.

REBUILDING BLOCKS

Hiring enough hands for the upcoming workload remains a sticking point for the restaurant and events industries. Nash Cognetti, executive chef at Pizzeria Tra Vigne and Tre Posti, a wedding and event space in Saint Helena, had 100 employees at the end of 2019. That dropped to a low of two last spring.

He now employs five, and is still not drawing a salary himself. “How do you gear up for event season again?” he wondered. “In the past, we could offer full-time employment.” With his industry shut down for 12 months, he saw an exodus of people who had chosen hospitality as their career, forced to find stable, full-time employment elsewhere. “We are hoping they love bartending at weddings more than painting houses or landscaping. But we are not in a position yet to offer full-time employment. It’s a big fat question mark,” Cognetti said. Even if there are new people ready to step in, “It is typically twice as expensive to train someone new to cook or serve as it is to train someone who already has those skills,” Ariosta said.

Cognetti does feel optimistic about the future. “The more people can host in spaces like ours—with 100% COVID standard operating procedure protocols—the safer we are all going to be. We are professionals and know how to properly sanitize everything,” he said. Like Ariosta and Conway, Cognetti expects the industry will go above and beyond the protocols to make guests feel safe. He is continually looking for new tools to help guests feel safer so that every segment of the Wine Country economy can return. “We offer a private space where the whole space is yours. That’s unique. Maybe some families require a COVID test before they attend. Or have people wear colored wristbands to show their comfort level with hugs and dancing. Let’s make people feel more comfortable.”

THE FUTURE OF REGIONAL AND NATIONAL INDUSTRY ADVOCACY

Pending further shutdowns by the state, Ariosta is trying to figure out what comes next for the Coalition she started. “Everyone is focused on getting back to business and it is harder, now that things are reopening, to keep people engaged,” she said. That may mean passing leadership off to someone else. She envisions an ongoing organization that could work together to lower health care costs, advocate for a cap on how much workers’ comp can pay out to insurance companies or working to eliminate the credit card fees restaurants pay on tips. She may have some help.

Bobby Stuckey, founder and owner of Frasca Hospitality Group in Colorado, set up the Independent Restaurant Coalition (IRC) in March 2020 to, according to the organization’s website, “help save independent restaurants and bars, the 11 million people they employ, and the additional 5 million people employed along the food supply chain who are affected by COVID-19.”

“We started because small restaurants, like a Korean barbecue restaurant in Queens or a single taqueria in East Los Angeles, has a different set of needs than a restaurant chain or a publicly traded company,” Stuckey said in our telephone interview. While the National Restaurant Association was the original advocacy group for restaurants, Stuckey and others realized an adjunct association was needed. “Our members were relentless in reaching out to senators and supporting others in different states. It took a lot of endurance. “

With the American Rescue Plan Act (the Act) passed in the early days of the Biden Administration, the IRC’s immediate task is working with the Small Business Administration on the execution of the $28.6 billion Restaurant Revitalization Fund included in the Act. “The most important thing is to get the money out,” Stuckey said. “$28.6 billion sounds like a lot, but it goes quick. That Greek diner in Detroit or Nebraska? They need this, and it is not just sending them an email and they’re in. We’re knocking on doors, asking distributors to help. Gotta make sure we do that.”

The IRC worked to make sure that any monies received from the Restaurant Revitalization Fund could be used for present, past or future expenditures. “If you are behind on invoices, you can shore up or pay current invoices. You can pay for your tent or gondola. And you can use it to ramp up, to hire new staff members who need training,” Stuckey said. “It’s almost like opening a restaurant—business owners can feel confident and able to do what they need with the Act.”

ADVOCACY GOES PRO

Like Ariosta and the Wine Country Coalition, Stuckey’s and other restaurateurs’ efforts with the IRC is 100% unpaid. For the organization to move forward, they will need to bring in outside staff who are not busy running their own restaurant groups or individual restaurants. “What we are doing right now is not sustainable,” he said. Over the coming months, Stuckey aims to have an election process to find leadership to run the IRC and bring in the national community of small restaurant owners. Right now, though, “People are exhausted,” Stuckey said. “Once we get through this, then we can figure out how membership should work, voting process, bylaws, et cetera.”

Back in California, Ariosta is still waiting to have a conversation about what comes next at the state level. “How do we prevent restaurants from bearing the brunt of continued fallout from the pandemic?” she wondered. Fire season will be here before we know it. Will the industry get an exception to let people sit inside if COVID—and fires—flare up again? Meanwhile, the job isn’t any different than it used to be, says Ariosta. “We don’t want to get you sick. We always have your best interests at heart. And we ask for your compassion if we cannot get staffed up the way we used to be.” This, it seems, is another part of the “new normal.”