A lingering Legacy

NATURALLY, M.F.K. FISHER’S “LAST HOUSE” HAS A TALE TO TELL

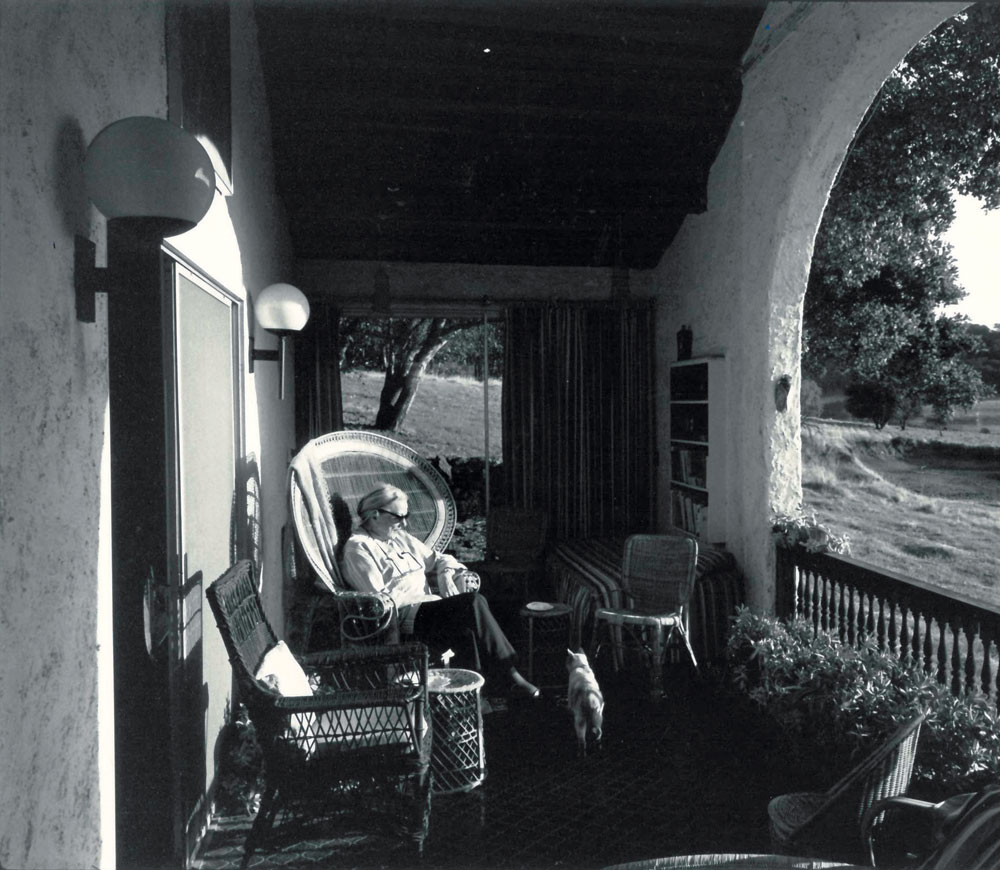

By now dark had almost come. I sat on the balcony feeling a little like the owl on the telephone pole, the hawk on the branch, waiting …. I waited, but everything looked as it always did from my balcony on a hot July night. The new moon was almost down, and a jet plane lowered itself gently toward the city, coming perhaps from very far away …. A supper of cold salmon and blueberries with cream tasted fine, if you care about those things, and I’ll sleep well ….

—FROM THE JOURNALS OF M.F.K. FISHER, GLEN ELLEN, 1980

Reading the lifetime of stories generated by food writer Mary Frances Kennedy (M.F.K.) Fisher—the exotic travels and sensuous meals, the raw and complex human behaviors and the difficult, painful, funny and, at times, transcendent descriptions of moments that a life on Earth can present—has always reminded me that being alive is a fragile privilege, one that offers great delights, and can also leave us utterly helpless.

It makes sense in a mystical way that “Last House,” the exquisite little corner of the world where Fisher spent her final 20 years (she passed away in 1992), an eclectic self-designed home on the property of her friend David Pleydell-Bouverie, would somehow survive last fall’s Nuns Fire in Sonoma County. After the fire was contained, Fisher’s small palazzina, as she called it, on the Bouverie property—now a 535-acre preserve in Glen Ellen owned and managed by the Audubon Canyon Ranch—was surrounded by burned land and devastation, and yet, almost miraculously, remained untouched.

In the words of Fisher’s daughter Kennedy Golden, who is part of an ongoing effort to preserve and restore her mother’s last home, “There are much bigger plans in the universe than we have any idea about.”

The story of the Bouverie Preserve, Last House and the Nuns Fire is a long and winding tale of care and details, much like the stories M.F.K. Fisher wrote herself. It starts in 1971, when the British architect and aristocrat David Pleydell-Bouverie, a good friend of Fisher’s, invited the writer to build a home on his land. Fisher had spent decades traveling the world and was living in Calistoga when Pleydell-Bouverie offered her a spot on his bucolic property just northeast of the town of Glen Ellen. The two picked a perch and an orientation for the home, nestled beneath a giant live oak and overlooking a wide expanse of lush green meadow. Fisher gave Pleydell-Bouverie the specifications and he constructed the adobe to her liking.

It is a modest home with just two rooms—a bedroom and a kitchen—plus an enormous bathroom and, most importantly, a long back porch framed in archways, offering an enchanting view for sitting, drinking, eating and communing with friends. This porch was essential to the home, as drinking and eating and communing with friends—Herb Caen, Julia Child and Alice Waters, to name a few—was central to Fisher’s life. Much of the interior of Last House was painted in her signature color, a vibrant “Chinese Red” and appointed with books, objets d’art and kitchen accessories from across the globe.

In 1978, Bouverie, who had established a relationship with local environmental activist and hero Martin Griffin and the Audubon Canyon Ranch (ACR), donated his large and ecologically diverse property, known for chaparral and riparian forests, waterfalls and magnificent spring wildflower blooms, to the nonprofit for conservation and education purposes. When Fisher passed away in 1992, a land steward moved into her home. Over time, as ACR established stewardship of the property, set up various offices, headquartered their Mountain Lion project at Bouverie and brought school children for extensive environmental education programs, there were ongoing murmurs of interest, mostly from M.F.K. Fisher devotees, about Last House.

“Three years ago, I got a call that there was some movement to do something with Last House, something that would benefit the vision for the preserve and ACR,” says Golden. “I was not interested in turning my mother’s home into a museum, but we began to see a way that we might connect her work to the preserve.”

The home had stood empty for a period of time and a vision began to evolve, a notion of bringing some of Fisher’s unique items back, offering a sense of her and how she lived, and reinvigorating Last House by creating a gathering spot for certain events and retreats. At Golden’s request, family and friends began to return objects they had inherited—paintings and photographs, books (including cookbooks), a kimono, a beautiful globe, her Coronamatic typewriter, her James Beard Award … even M.F.K. Fisher’s favorite rattan chair and the round wooden table where she fed her beloveds. The walls were re-painted Chinese Red to complement the black tile floor, which remained in excellent condition, and although no one hoped to exactly replicate her home, the essence of M.F.K. Fisher’s sensibility began to fill the space.

Last June, a group of inspired chefs and artisans, led by local chef Sheana Davis, and 100 guests—friends, family and followers of M.F.K. Fisher—gathered for an event called “First Meal, Last House.” Beautiful food, some of her favorite dishes, was served on an eclectic china collection, which guests brought, signed on the back, and left at Last House.

“I ended up telling a million stories that day,” says Golden. “My mother’s house has its own spirit, and everyone was so excited to be there. It was visceral confirmation that this was the right thing to be doing.”

Meanwhile, as plans for the “First Meal, Last House” event were developing, something very important, although seemingly unrelated at the time, was happening in the foothills of the preserve above David Pleydell-Bouverie’s historic home and Last House. Dr. Sasha Berleman, a PhD fire ecologist and director of the ACR’s Fire Ecology initiative to use burns as an essential element of their resource management, conducted several prescribed burns on Bouverie. According to Berleman, prescribed burns have been part of the Northern California ecosystem for thousands of years as Native American tribes regularly used them to encourage the health and productivity of the land. Not only do these burns clear the understory, but they encourage the growth of many plants specifically adapted to fire, native plants and bulbs that are designed to grow or reproduce only after a fire has passed through.

“For the last hundred-plus years we have been suppressing fire,” says Berleman. “Before that the fire would essentially clean the forest. But when American settlers arrived and began suppressing fire, these landscapes that relied on fire no longer had that fire and carried a very high fuel load.”

In the spring of 2017, with no way of knowing what the coming months would bring, Berleman oversaw three prescribed burns in different areas on the Bouverie land. One of the burns covered 20 acres just above David Pleydell-Bouverie’s home and Last House.

Just a few months later, on the night of October 8, 2017, the Nuns Fire ignited. Over the course of that wildly windy night and the following week, the fires swept rapidly across the region, burning 56,556 acres in Napa and Sonoma and destroying over 1,000 structures. On the Bouverie Preserve, seven out of nine buildings were lost, including housing for three resident biologists and resource managers and offices for 12 ACR staff members.

Although the destruction was extensive, the fire’s progress and ferocity was slowed when it reached the areas of forest and grassland that had been “cleaned” by Berleman’s work. With buckets, water from Pleydell-Bouverie’s pool and the assistance of two neighbors, Berleman was somehow able to prevent the wildfire from destroying the central part of David Bouverie’s historic home. Sleeping in her car overnight, she was also able to put out the spot fires that would jeopardize Last House and so many of M.F.K. Fisher’s treasures.

Fast forward to early spring, three months after the Wine Country fires were fully contained. Wendy Coy, Audubon Canyon Ranch communications manager, walks me around the remains of the gathering hall and offices that housed the docent training, educational programs and day-to-day staff of ACR on Bouverie preserve.

“That was where my desk was,” she says, pointing to a twisted pile of debris standing amidst a carpet of ash. We walk around the southern perimeter of Pleydell-Bouverie’s home—pristine and untouched from that angle—and make our way down to Last House. The burn marks creep up to the house from different directions, yet stop abruptly as they near Last House. The most remarkable is the forested side, where the live oak arches over Fisher’s kitchen.

“It just petered out,” says Coy. “Live oaks don’t carry fire, and someone said that this tree may have created its own environment and helped protect her home.”

Inside Last House the rooms are still and quiet, filtered light reflecting off the Chinese Red walls, illuminating shelves carefully lined with Fisher’s books. Her chair sits in the corner, a bouquet of wooden cooking utensils fills the metal tureen next to the kitchen sink. A note in her handwriting, complete with a sketch, asks that visitors not let her cat out. The home feels peaceful, settled into the landscape and a good place to think and appreciate from a distance the intricacies of life. Here there is no sense of the raging fire that has only recently passed over the surrounding landscape.

Rebirth. That is the feeling that emanates from the sun-soaked land as Wendy Coy and I leave Last House and make our way up a trail toward the foothills of Bouverie. Here, you can see the blackened earth on one side of the trail, an unrelenting path of heat that burned voraciously, fueled by decades of understory growth. Then, across the trail the perimeter of one of the ACR prescribed burns becomes apparent. The oaks and mixed evergreen trees look lightly touched, if touched at all. The grassland is marbled in shades of blond and brown rather than charcoal black.

We wind farther up the trail, heading toward the base of the Mayacamas Range and stopping at a spot high enough to have a view of the valley below. We look down over the pathway of the fire; from this perspective, the fact that any of the buildings on the preserve stand becomes even more miraculous.

But amongst the destruction, Coy is beside herself. “Knobcone pine cones are adapted for fire and now they are dropping and opening,” she says. “And our newts. We are known for the newts here on the preserve. Soon after the fire one of our biologists made it up to an area of Stewart Creek we were worried about because it got very hot, but he counted 30 red-bellied newts!”

She points out signs of survival and rebirth in every direction. These are not signs easily noticed by the naked eye, but if you stand still in one spot for long enough, the pin-pricks of green come into focus: the tiniest new leaf poking out from a grey and brittle-looking oak bough, a sea of native bulbs—including wild iris, delicate rose and hazelnut sprouts, and white Clavaria fragilis fungus, or “fairy fingers,” all making their way up through charred ground.

In this nuanced post-fire landscape I cannot help but think of M.F.K. Fisher and the way she settled into a place or a moment in time and observed, identifying and giving meaning to details. She also moved through so many difficult periods in life—an extraordinary amount of personal loss—with both honesty and resiliency, cherishing the elements of life that bring pleasure, joy and hope.

For M.F.K. Fisher’s daughter, the revitalization and restoration of her mother’s home on Bouverie is part of a larger storyline of renewal, interconnected with the landscape.

“They are all in one sentence, as far as I am concerned, and I hope that in the future we can provide endless opportunities to enjoy Last House and the Bouverie preserve,” says Kennedy Golden. “I am so terribly sorry that we were reminded in such a fierce way of our humanity, but the voice of resiliency is there, and it is very powerful.”