Seeking: Harvesters, Urgently

DEPORTATION THREATS, RAID FEARS, HOUSING WOES WORSEN WINE COUNTRY IMMIGRANT LABOR CRUNCH

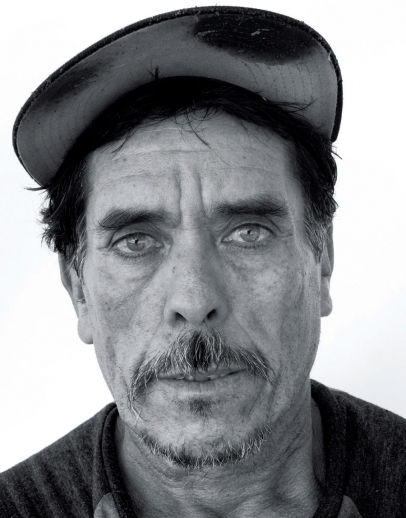

Jesus Ordaz is nothing if not persistent. And patient. These qualities have served the Mexican immigrant and vineyard whisperer well. It took 33 border crossing attempts for this vegetable farmer’s son from Palo Alto, in the southwestern state of Michoacán, to successfully make it into the United States. That’s not a typo: His 33rd attempt, he says, did the trick.

Fortysomething years on, Ordaz is a bit of a legend in Sonoma wine industry circles—for his grape growing prowess, never mind his tenacious efforts to land here in the first place. Ordaz, who goes by the nickname Chuy (pronounced Chewey), runs Palo Alto Vineyard Management, a farm labor contracting company in Kenwood. His Wine Country client list includes high-end premium labels such as Arnot-Roberts in Healdsburg; Bedrock in Sonoma; DuMol in Windsor; and Neyers and Turley, both in St. Helena.

Winemakers have even named bottles after Ordaz—no small honor for a vineyard manager. The Eric Ross Winery in Glen Ellen features a full-bodied Cabernet Sauvignon dubbed The Immigrant, after the farmer. Failla Wines in St. Helena markets a popular “Chuy Vineyard” Sonoma Valley Chardonnay. Typically, wines from the vineyards Ordaz manages cost $25 to $100 a bottle, placing them in the premium/luxury segment of the wine market.

Ordaz, now 64, could serve as a migrant poster child—even though he arrived here under a legal cloud. He’s worked hard for employers, gone on to employ hundreds himself, raised a family, sorted out his residency status and become a citizen. Starting with nothing, he moved up in the industry via his knack for coaxing the best out of vines, a commitment to sustainability (better for both the land and the people who work it) and his reputation as a leader in the fields. Today, he’s a sought-after and respected vineyard manager.

“Chuy is just a natural at what he does: He’s also completely loyal, totally trustworthy and sees the big picture. He’s always looking ahead and thinking about what needs to be done,” says Kaarin Lee, who owns the 57-acre Montecillo Vineyard in Glen Ellen. Lee and Ordaz go back 40+ years, to Kenwood Winery, where he landed a job soon after arriving in Sonoma. He worked at Kenwood, which Lee co-owned, for three decades until the winery was sold. “He’s a genius in the fields. He’s also a great human being: sincere, caring, conscientious.”

“Chuy takes what he does personally. He farms for you like he’s farming for himself. He’s also a great mentor, he’s taught me everything about the vineyard and he’s done that for so many people,” says Todd Maus of Maus Vineyards. “I call him the Mayor of the Vineyards, you see him pulling out of so many vineyard driveways, he works everywhere.”

A self-made man of the land, his passion for grape growing is palpable on a brief visit to a picture-perfect client vineyard. Trim, fit, with one impressively calloused hand from years of wielding pruning shears, Ordaz has worn the same uniform his whole working life: baseball cap, button-down shirt and jeans.

Today, one of his sons, Chuy Jr., works with him in the vineyards. Another, Epifanio (“Eppie”), an accountant-turned-winemaker, now runs the clan’s own label, Ordaz Family Wines. Both spent summers alongside their father in the fields. “As difficult as it is to pick grapes, there’s a great camaraderie in the vineyard,” says 36-year-old Eppie Ordaz. “My dad has integrity and high standards: If I missed any grapes in a row he’d point them out to me. He expected nothing less than 100% effort. I’d go back and get those other bunches.”

BAD HOMBRES: GET THE JOB DONE

Chuy Ordaz is no “bad hombre.” Yet in today’s political climate—a combination of anti-immigrant rhetoric and tightened-border reality—it’s tough to imagine that a young man like the 1970s-vintage Ordaz would have a chance of coming to the U.S. safely. The Trump Administration’s stepped-up Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) efforts and the prospect of a border wall—which Trump promised voters—act as strong deterrents for the undocumented to attempt to enter the U.S. and translates into many fewer harvest workers.

“All the talk about a more secure border is scaring Mexican people at a time when it’s already hard to find labor. I have a crew of about 35, but I could use 50 and closer to 60 at harvest,” says Ordaz. “I’ve had to cut back on the acres I cover,” he adds, a loss of about 150 acres in the past three years due to the worker shortage. At least 75% of the almost entirely Mexican crew who work for Ordaz likely don’t have legitimate documents, he says, a figure that he believes holds true for similar companies in the industry.

How can that be? The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission advises employers not to ask potential job applicants about their citizenship status before making an offer of employment. Employers should also accept “any unexpired document from the Lists of Acceptable Documents so long as the document appears reasonably genuine on its face.” Of course, there has long been a robust underground market for fake papers. Eleven percent of Napa residents and almost 8% of Sonoma residents are undocumented, according to recent estimates from the Public Policy Institute of California. According to 2016 estimates from the University of California, Davis, about 60% of California’s roughly 471,000 farmworkers are in the country without authorization. That’s one of the not-so secret realities of the multi-billion-dollar California wine industry: It’s built on a decades-long reliance on undocumented immigrant labor.

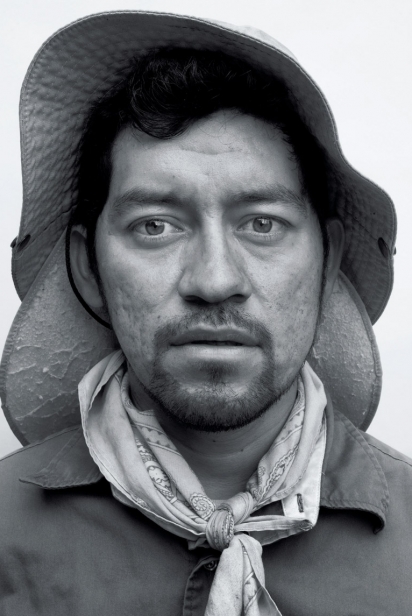

And they do a job few want to do. Ordaz starts workers at $16 an hour—labor costs have jumped significantly in the last three years—and pays as much as $22 for seasoned crew members. These laborers typically work a 60-hour week: six 10-hour shifts, which begin in the middle of the night, when it’s cooler to pick.

“This is very hard work. Nobody wants to do it,” says Ordaz, of the manual labor he does with pride. Ordaz plants, prunes, thins, waters, weeds, and picks alongside his crew, some of whom have worked with him for decades. His team is mostly male, though increasingly female workers are in the mix. Ordaz has hired exactly two white American men in 40 years. Neither lasted more than a day. “The only people willing to do this work are from Mexico,” he says. “I don’t know what’s going to happen in the future.”

VINEYARD WORKERS: BY THE NUMBERS

It’s not just fear of deportation that’s causing a labor crisis in Wine Country. Affordable housing and access to health care have long been issues in the region—this magazine covered those very concerns seven years ago [See Edible Marin & Wine Country’s Fall 2010 issue online]. Given steep Wine Country area housing costs, workers are commuting from as far as Yuba City and Stockton, which vineyard managers maintain simply isn’t sustainable in the long haul.

And there are other, potentially more lucrative and less physically demanding, ways to make a living. Cannabis cultivators—so-called trim-migrants—can make as much as 35 bucks an hour in cash. Restaurant and hotel jobs are more attractive to workers who’d prefer not to toil in the bitter winter cold and rain or brutal summer heat. Even construction jobs are considered less taxing on the body than field work. Meanwhile, an improved economy in Mexico means that some potential U.S. farm laborers are opting to stay put and work the fields at home instead.

Indeed, a once-steady stream of Mexican laborers relocating to work American soil has slowed to a trickle. U.S. agriculture is losing Mexican farm labor at a rate of almost 11,000 people a year, according to estimates from UC Davis. And, unlike the Italian and Portuguese immigrants before them, another migrant group hasn’t emerged to take the place of Mexican farmhands. Field workers are an aging demographic, and fewer children of grape harvesters are joining their parents to work in the fields, say vineyard managers.

Once as rare as a beer drinker in Wine Country, women are increasingly showing up in the fields. “We have seen an increased female presence in the vineyard, a spike of about 25%,” says Blanca Wright, chief financial officer of Renteria Vineyard Management, a Napa-based, family-run company that has 80 full-time employees, about 280 seasonal workers and around 1,500 acres under its care. “Some commute with their spouses; we have female supervisors who are responsible for both male and female crews.”

What does all of this mean for the wine industry? Higher wages, for one thing. The average wage for Sonoma vineyard workers is $16.34 an hour, which is 60% above the current state minimum wage of $10.50, according to industry group Sonoma County Winegrowers. Napa Valley vineyard pickers are among the highest-paid agricultural workers in the country, earning around $17 an hour as a starting wage. Skilled vineyard workers can make as much as $25 an hour, according to the trade organization Napa Valley Vintners, citing state Employment Development Department (EDD) data. During peak picking months, workers can reportedly earn $30 or more an hour. Napa County pays farm laborers $41, 940 a year, the highest farm wage in the state, according to an analysis of federal figures by the Los Angeles Times. Still, some vineyard managers are reluctant to quote hourly rates: Worker poaching is a real thing.

But raising wages and providing benefits such as paid vacation days, health insurance, 401(k) retirement plans and compensation for attending English classes, as some employers do, hasn’t solved the labor shortage problem. Take Sonoma County. The number of ag workers here—the majority of whom work in viticulture—was estimated at 7,100 in May 2002, according to EDD data. In May 2017, that figure dipped to 6,800. Meanwhile, the numbers of wineries (over 400) and vineyard acres (almost 60,000) keep growing. Demand for fine wine is increasing, too.

Something has to give: Winemakers must choose between absorbing costs and lowering profit margins or passing on the expense to drinkers. Indeed, expect to see small price hikes in the premium and high-end luxury wine segment in 2017, predicts Rob McMillan, in the widely referenced Silicon Valley Bank 2017 Wine Report, which also notes that farm labor supply and costs are the current dominant industry concerns.

Despite heightened fear in the fields, there haven’t been reports of ICE raids in the Wine Country since the 45th president took office in January—unlike elsewhere in the state’s ag lands. There are rumblings, though, of asset seizures of vineyard workers with less-than-pristine documentation. And some undocumented workers with criminal records have been deported, say vineyard managers, a practice that was on the upswing even before President Trump took office.

An overhaul of immigration laws could provide some relief from the labor drought. But when? Legislation introduced by Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) and a handful of other Democrats, known as the Agricultural Worker Program Act of 2017, would protect field workers from deportation and provide a pathway to legal status and eventual citizenship. “Wherever I go in California—I was just up in the wine industry—they tell me they can’t find workers,” Feinstein said on a conference call with reporters announcing the bill in May. “Workers are scared, they’re afraid they’re going to be picked up and deported, [some have] disappeared…. The people who feed us should have an opportunity to work here legally.”

With the prevailing get-tough-on-illegal-immigrants sentiment in the White House and conservative-dominated Congress, chances of the bill passing are considered slim. Given that political and legal vacuum, the industry is looking elsewhere to address the problem.

IS AUTOMATION THE ANSWER?

Some agricultural companies are now using machines to do labor formerly undertaken by humans. Driscoll, the global berry grower based in Watsonville, is mechanizing its flat fields in a major way. But tending vines on hilly, terraced terrain is a trickier proposition for automation. “Look at this land,” says Ordaz, gesturing towards one such vineyard. “You can’t get a machine in here to do the job. It’s impossible. It’s all hand-picking here.”

Many vineyard tasks—tying, pruning, suckering (removing unwanted shoots) and cluster thinning—have long required a personal touch. But automation may fill a labor void in some settings. Still, for many winemakers how grapes are picked, which can impact the wines they make, is a top concern. “We own a harvester to machine-pick some of our vineyards,” says Blanca Wright, but “most of our clients still appreciate hand-picked fruit.”

Elsewhere in Wine Country, though, machines are gaining traction in an absence of hands. “We’re all in the same boat: We’re down about 30% in the last three years in terms of workers and we’re not out there looking, there’s nobody out there to hire,” says Ned Hill, owner of La Prenda Vineyards Management in Sonoma. La Prenda looks after around 900 acres for more than 25 vineyard and winery clients, from nationally known labels to boutique brands, including Hanna Winery & Vineyards in Healdsburg, Roche Winery & Vineyards in Sonoma and Schug Carneros Estate Winery, also in Sonoma. “So we’ve made up for the labor shortage with machines. We’re much more mechanized: We offer mechanical leafers and mechanical harvesters. Last year half of all the fields under our care were harvested by machines; five years ago: none.” That said, Hill confirms that small-scale mountainside vineyard clients still want their grapes hand-picked.

Of course, there’s the initial investment in expensive equipment up front to consider. Such costs can put mechanization out of reach for modest-sized vineyard management operations. That’s not the case for larger-scale companies. “We are using machines for everything we can get them to do,” said Rich Schaefers, viticulturist for Silverado Premium Properties in Napa, the third-largest vineyard owner in Sonoma County, in a July 2017 Santa Rosa Press Democrat story.

Will machines eventually completely replace the human touch in vineyards? Unlikely. “As long as we’re farming hillside vineyards we’ll have to have some amount of labor available to do some of these tasks, including harvest,” says Duff Bevill, of Healdsburg-headquartered Bevill Vineyard Management, in a video accompanying the Press Democrat story. Bevill, who is set to work his 44th harvest season, employs around 60 full-time workers year-round. That number can double during peak periods. His extensive client list includes large international wineries and small-scale players in both Sonoma and Napa counties. About 40% of the 1,000 acres under Bevill Vineyard Management care is now picked by machines.

While some embrace mechanization on flat land as the new wave of vineyard management, other growers aren’t yet convinced. “I’m interested in machine harvesting and other mechanized equipment, but our fruit is very high quality and too fragile to pick mechanically,” says David Hirsch, of Hirsch Vineyards in Napa. “As the equipment improves it may be feasible in the future.”

TEMPORARY WORKERS HELP FILL THE GAP

How else to handle the labor drought in Wine Country? The U.S.’s temporary visa program, known as the H-2A guest worker program, is generating interest as a potential solution. The program is becoming more popular across the Golden State: In 2008, 3,353 H-2A visas were issued in California. In the first half of 2017, more than 11,300 have been approved. These figures represent workers across all agricultural areas; to date, the wine world has underutilized the program compared to other industries. That may be changing. In 2016, for instance, strawberries (3,695 guest workers) and lettuce (2,052) accounted for most of the H-2A visas issued in the Golden State; grapes, on the other hand, used just 246 temps, according to L.A. Times data analysis. This year, some 300 such temporary, seasonal agricultural workers are in Sonoma County alone.

Among the local operations going the guest worker route: Bevill Vineyard Management reportedly brought in 24 H-2A workers from Mexico this year. The program allows agricultural employers to hire at fair wage rates—and expects them to house—these workers for jobs lasting up to 10 months.

At least one vineyard jumped on the H-2A bandwagon a decade ago. After losing 150 workers during the 2007 growing season, Seghesio Family Vineyards in Healdsburg began bringing guest workers into the country in 2008. The vineyard harvests 300 acres and purchases fruit from 40 other growers. Guest laborers proved a savior during a time when the company was hemorrhaging resident workers. It was a no-brainer.

The program is not without obstacles: For some, the numbers simply don’t pencil out. The cost of registering 34 H-2A workers, before wages, for the 2018 year at Seghesio totaled $41,653, according to a July San Francisco Chronicle story on the vineyard’s program. For others there is no other option. “We simply wouldn’t be in business without H-2A workers so we have had to make it pencil out,” says David Hirsch, who brings in 12 H-2A workers each year.

Employers are also required to provide housing, transport and meals, in addition to covering legal and visa costs. Accommodations are routinely inspected by government agencies. Workers need to be recruited in the first place, which can involve sending an employer to Mexico to scout potential hires. And, of course, there is the resulting two-tier system and the tension that can create between temporary workers and full-time resident employees.

Ted Seghesio, general manager of Seghesio Family Vineyards, has no reservations about the program. “It is a great resource for a labor force you can count on,” he says. The fact that many of their H-2A workers return each season is validation that it works, says Seghesio. “We have presented our H-2A program to all our growers in hopes that they will realize that H-2A is a viable solution for harvesting fruit in a timely manner.”

The guest worker program is not without its detractors. Some farm worker advocates maintain that employers use the program to avoid paying local workers higher wages. Temporary workers also have limited rights; they can’t leave their jobs or switch employers. Critics argue such conditions leave them vulnerable to abuse or mistreatment, though no such allegations have surfaced on that score with regard to the Wine Country companies utilizing the program interviewed for this story. There’s also the hardship aspect: Guest workers are separated from their families for much of the year. On the other hand, many of these laborers are able to provide for their families back home due to these jobs.

Despite campaigning on a “Hire Americans First” platform, President Trump has himself hired temporary foreign workers, including seasonal, non-agricultural workers on H-2B visas at his estate Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida. In December 2016, and then again in February 2017, his son Eric Trump petitioned the Labor Department to import a total of 29 H-2A workers to tend the family winery in Charlottesville, Virginia. In July, the Department of Homeland Security announced a one-time bump of 15,000 H-2B guest worker visas through the end of the year. Three days later, a Trump resort and golf club promptly requested 76 such visas. (There is no cap on H-2A visas.) During the first three months of 2017, the Department of Labor approved applications to fill 69,272 farm jobs with workers on H-2A visas. That’s an increase of 36% over the same period the previous year.

Vineyard owner and winemaker Todd Maus is awaiting word from the county regarding building a house on his vineyard property to accommodate both full-time and temporary workers, somewhere between six and 10 people, he hopes.

“We have to find a solution to do this in a legitimate way, housing is just getting too expensive for our vineyard workers. I watched a French documentary about farmworkers who lived on site and I just thought, why don’t we do that here?,” Maus says. “Yes, there’s the initial expense, but you have to take the long view: What is your obligation to the people who pick the fruit that goes into your wine? It’s the right thing to do.”

A MAN AND HIS VINES

In four decades, Ordaz has seen a lot of changes in his chosen field. And he knows more are coming. Despite the current industry challenges, nothing seems to faze Ordaz, who first attempted to cross the border in Tijuana at age 20, with his younger brother in tow. He tried daily, nightly, often more than once in a 24-hour period to run across a bridge into California. U.S. Border Patrol agents repeatedly caught the brothers and sent them back to Mexico. His younger brother eventually made it across weeks before Ordaz. His son Eppie teases him about how many times it took his dad to sneak across. When he did, a human smuggler, or coyote, found a safe place for him—for a hefty fee—deep in Sonoma County chopping wood, well off the radar of what was then known as the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Within six months he graduated to grape picker, when he went to work for Kenwood Winery. Early on in his Wine Country tenure he met and married an American; a green card offered protection and rendered questions about his tenuous legal status moot. He and his wife, Beverly, who keeps the books for Palo Alto, have six children, three of whom have gone to college. Ordaz knows he got lucky: personally and on the job front. Many of the workers he’s worked alongside or hires aren’t so fortunate.

Ordaz taught himself to make wine, a hobby he’s parlayed into the family’s own wine business, which features high-end, single-vineyard wines from local sources. Currently, the brand includes a Pinot Noir (Placida Vineyard), Malbec (Sandoval Vineyard), Zinfandel and Cabernet Sauvignon (both Montecillo Vineyard) and rosé (Maus Vineyard). The winery label, which depicts a dahlia, is a nod to both the senior Ordaz’s love for growing flowers and the family’s heritage. The national flower of Mexico, the dahlia symbolizes culture, beauty, diversity, grace, personal expression and commitment: qualities that are prized in people as well as wine.

In many ways, Ordaz’s story is that classic immigrant success story: Proof that the American Dream for newcomers is possible.

There’s one last piece to complete the picture: Ordaz is searching for just the right land to purchase to grow grapes for his clan’s wine company. A deal in the Kenwood area fell through last year, but it seems unlikely it will take 33 attempts before he makes his first vineyard property purchase.

Given Ordaz’s tenacity, expect him to cross that goal off his to-do list in due time.