Truly Farm to Table: Tight Bonds Between Full Table Farm & Bar Tartine

It all began with a bumper heirloom tomato harvest. A full table, in fact. In 2010, Mindy Blodgett and Juston Enos, then recently relocated to Yountville, decided to share their home garden surplus with local restaurant chefs and fellow residents at the Napa Farmers’ Market. Full Table Farm seemed as apt a name as any.

They were, apparently, really, really good tomatoes. Plump, juicy, saturated with tomato-y deliciousness. Chefs at restaurants including Kitchen Door, TORC and Terra in Napa couldn’t get enough of them. And they wanted to know what other tasty excess produce Blodgett and Enos had to offer.

Soon the pair found themselves with multiple restaurant clients. Another notable early supporter: Michael Tusk, chef/owner of acclaimed Cotogna and Quince in San Francisco. You get the impression the pair could pinch themselves at their good fortune.

“It is surreal to be working with or having worked with talented restaurant chefs, catering teams and passionate home cooks, many of whom have become friends,” says Enos. “This business has brought us a true gift.”

In a few short years, what started as a hobby garden in their backyard, designed to simply feed the family, turned into a thriving full-time farm business, complete with top-tier restaurant accounts. These days, Blodgett and Enos grow exclusively for celebrated San Francisco restaurant Bar Tartine. That acre out back is now filled with flowers and herbs—all destined for the dining room. On an adjoining acre they grow row crops for the restaurant. Lots of them.

Blodgett and Enos defy Wine Country farmer stereotypes. They don’t grow grapes or have family roots in the region. They’re not refugees from medicine, law, Hollywood or, more recently, tech. They are, however, transplants from the Central Valley—where farms are measured in hundreds of acres. They joke that the folks back home in Escalon, near Stockton, think they’re NorCal hippies now and that two acres hardly qualifies for farm status in their minds. The husband-and-wife growers are down-to-earth, humble. They’re also hard-working souls.

“We keep it simple,” says Enos, 38. “We grow stuff, the chefs at Bar Tartine make stuff, and the people who dine there eat the stuff we grow and they make.”

GROWING A BUSINESS FROM THE GROUND UP

Childhood sweethearts, the couple married young. Blodgett’s father was a high school agriculture teacher; Enos’s uncle had an almond and peach farm. Enos grew up driving tractors and fixing sprinklers. Still, he never imagined he’d be a farmer himself one day. He and Blodgett, 36, moved to San Francisco in 2007, for a taste of city life.

They landed in Russian Hill and were hooked. So much good food. Enos’s job working for a company that focuses on cancer research and testing was sufficient to support them both. Blodgett dabbled in different pursuits, never quite finding her thing. They eventually moved to Noe Valley and continued to enjoy urban life, yet they hankered for some space to grow their own food.

They got lucky on a foreclosure and moved to Yountville at the end of 2009. Their modest home, which needed plenty of TLC when they bought it, sits on an acre about a half-mile from town. Right off the main drag, there’s a steady stream of traffic noise on the weekend and the Napa Valley Wine Trolley runs between their property and their neighbor’s land, which they also farm under a handshake agreement. Both were weedy wastelands when they first moved in. The pair set out to clear the backyard, tend the well established but long neglected fruit trees on the property (including Blenheim apricot, Santa Rosa plum, Babcock peach, Granny Smith apple and Bosc pear) and plant a kitchen garden.

Fast forward to the end of 2011. That’s when Blodgett began delivering produce to Cotogna and Quince in San Francisco. Bar Tartine became her regular lunch spot before she headed home. She liked the menu at the Mission District restaurant known for its preservation pantry and layered flavors.

“Their food is always generous and full of integrity,” says Blodgett, who grew up canning and cooking. “If you pay attention to the ingredients on the plate, it can be a profound meal based on years of inquisitiveness, learning and hard work.”

The culinary pair behind Bar Tartine intrigued the farmers. In the winter of 2013 they attended a panel at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, where Nick Balla and Cortney Burns discussed their DIY stance on crafting everything in house from spice mixes and salumi to kefirs and krauts. The two couples spoke after the discussion and they talked again at a related dinner a week later. Something clicked. The chefs invited Blodgett to swing by in the spring with produce in tow. That was all it took: Bar Tartine quickly became Full Table Farm’s newest and biggest customer.

Co-chefs Balla and Burns joke that the farmers stalked them, or maybe it was the other way around. Either way, it was a meeting of the minds among produce nerds with a shared philosophy around food and farming.

Entering into an exclusive relationship with the restaurant in 2015 wasn’t a hard call. It makes sense practically and financially. Fewer clients to serve means fewer deliveries, too. The farm income now covers many of the couple’s larger personal expenses including mortgage and property taxes, as well as the costs of running the operation.

It also just felt right. “We appreciate the independence they give us to make planting decisions, trusting us to know what we can do best in the field,” says Blodgett. “We like that they value the gifts of the land as much as we do, using or trying to use everything imaginable from a plant. The biggest reason, though, is that they bring out the best in us as growers.”

Blodgett works the two-acre farm full time; she has found her calling. She devotes one day a week to canning, jamming, pickling and dehydrating for personal use. Enos helps out in the mornings, evenings and on weekends. Basically, every minute he can when not at his day job.

PLAYING WITH SEEDS, EXPERIMENTING WITH PLANTS

The chefs, always striving for optimum tastes and textures, aren’t afraid to entice the farmers to experiment.

Case in point: their paprika project. The Bar Tartine crew wanted a reliable, local source of paprika of the quality Eastern Europeans would happily sniff at. So they worked together to source seeds and cultivate pepper plants that produce a paprika that’s closer to the version Balla, who has Hungarian roots, wanted to emulate. After three generations of breeding from seed and using Old World methods on the farm to prepare the peppers for grinding, they’re all pretty happy with the paprika they produce, says Enos.

But if not for Bar Tartine, the farmers probably wouldn’t have even attempted to grow paprika pepper. There simply isn’t another market that would make all the work involved worthwhile, they say. Sometimes it takes an investment of two or three years before the crop is ready for prime time. That’s a risk the restaurant is willing—make that wanting—to take.

“This year they have asked us to grow winter melon, sesame and mitsuba, a Japanese parsley, which we haven’t done before,” says Blodgett, clearly jazzed by the prospect. “Last year they got their hands on some black soybeans from Japan. We took those soybeans and planted a crop to save seed from; this year we planted them out for harvest.”

Enos has been saving seeds since he was 6, when he started collecting marigold seeds from his front yard. As a farmer, it makes economic and practical sense, it’s relatively easy to do and solves the challenge of finding hard-to-source seeds. But there are significant, secondary benefits.

“By selecting seeds from our best plants, we improve the quality of the produce and the plant,” he explains. “We immediately notice fewer serious pest problems or disease and healthier, more vigorous and tastier plants and we select plants that do well in our environment and soils.”

He is a hardcore seed saver. Enos says it’s cool to play around to see what happens when two different types of tomatoes or cucumbers get together. “You don’t always end up with something special, but sometimes you do and that’s great fun.” He knows varieties: He can rattle off the pros and cons of different cucumbers; one year the farmers grew 36 different types. He points this writer to a lemon variety sans spikes, making eating the skin a no-brainer. Duly noted. Next year.

Although he has no formal science training—he was a business major—Enos works in a science-minded environment and says he has always had a curious nature. “I often joke that every day I walk out into the farm I’m reminded that no matter how much I have learned about growing, I am still a fool,” he says. “But it’s not a joke. It’s the truth.”

The farmers grow ingredients for a diverse range of uses: Their harvest ends up in teas and garnishes, pickles and pastes, sauces and salads. They seek out unusual crops, such as dulce buttons, an herb that might move diners away from refined sugars while still satisfying a desire for something sweet. And they plant familiar row crops such as squash, tomatoes and eggplants.

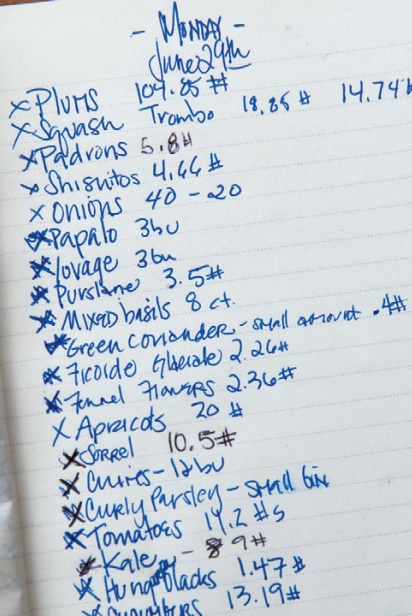

“We will grow over 200 varieties of produce for the restaurant this year and they are committed to using every single piece,” says Blodgett. “As a grower, you couldn’t ask for anything more.” In 2014 they delivered 10 tons of produce to several restaurants; they’re on track this year to surpass that figure for Bar Tartine alone.

In the mix: produce exotica such as horned mustard (a pungent frilled Chinese green); bell beans (a fava variety); Aji dulce peppers (similar to a habanero but without the heat); cornichon (sour gherkins); cucamelons (grape-sized cucumbers); tromboncino (a serpentine-like summer squash); snake gourds (a South Asian elongated green with a buttery taste); and celtuce (Chinese stem lettuce).

It’s fun times with less-familiar produce. And these adventurous growers are game. Even what stage of ripeness to pick a fruit, vegetable or nut is a collaborative affair. “They have us harvest things that we normally wouldn’t, like immature green walnuts, as well as fruit tree blossoms, such as apricots,” says Blodgett.

During the fallow months—in non-drought years their backyard gets too flooded in winter to plant—Blodgett and Enos curl up with seed catalogues and plot and plan. Balla and Burns consult with the growers then, too. It’s a favorite time of year for the farmers, a chance to rest and recharge after the frenetic planting and harvest seasons. A time when anything is possible.

PARTNERS ON THE FARM AND OFF

These two make working and living together look easy. The mild-mannered husband-and-wife farmers enjoy a similar sense of humor, frequently on display. Although they don’t take themselves too seriously, they’re dedicated to their work, have a strong sense of purpose and are committed to harmoniously dividing the farm chores. Blodgett, the more reserved of the two, tackles some of the more tedious harvesting; she’s also in charge of the greenhouse. Enos, who likes a chat, handles tasks that require height or brawn; he can be found behind the mower and tiller. They both enjoy the physicality of the farm, sowing seeds and starts, weeding and picking.

In a follow up to an in-person interview, Enos sent a lengthy email detailing what he most admires about his wife. It was the kind of mash note many longtime partners would welcome.

“I know without a doubt that the reason we are so well thought of in the culinary/farming community is because of Mindy,” wrote Enos, praising Blodgett for her growing skills, high standards, cooking acumen, exceptional palate and bountiful common sense. One of the true joys of building the farm together, he noted, is in simply seeing his wife in her element every day doing something she loves, so well, and so successfully. There’s a man who isn’t afraid to lean in and give credit where credit is due.

Eating at the restaurant brings these farmers full circle. They feel appreciated, inspired and, of course, well fed. They admit they’re delighted to look around the dining room and watch guests happily tuck into the fruits (and vegetables) of their labor. It’s more than that, though. Planning their next planting, cultivating their own produce, seeing it plated by chefs at the top of their game and finally savoring it in their mouths satisfies a deeper hunger.

In July, the couple celebrated their 16th wedding anniversary at Bar Tartine. Standout menu items showcasing both the chefs’ culinary chops and their growing skills: a dish that featured their tender greens beans with sumac yogurt and lovage, a pungent celery-like herb exhibiting its best flavor profile since Full Table began growing it, according to the farmers. And a roasted tomato and squash dish with sunflower tahini and in-house farmers cheese that practically screamed summer. On a previous visit, the stone-fruit soup wowed; it highlighted their fresh plums in their prime.

At this recent meal, Enos recalls he felt like Burns and Balla had captured the terroir of Full Table—the flavors of the food instantly transporting him back to the farm—in a way he hadn’t experienced before. It tasted, in the best possible sense imaginable, like home.

For these relatively new farmers, it doesn’t get much better than that.