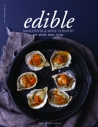

A History on the Half-Shell

Hog Island Oyster Co. marks four decades as a pearl of the local food scene

Having raised and served up delicious shellfish since 1983, Hog Island Oyster Co. continues to innovate, grow and inspire as pioneers in the regenerative food space. They’ve shown that a successful business can be good for the environment and the community—and demonstrated that resiliency requires a blend of science, creativity and business acumen. The team at Hog Island has set a standard for excellence in the food world, built a powerful brand and continue to vertically integrate their bivalve empire.

Oysters are a regenerative food because they improve the estuaries where they are cultivated, support habitat for many other creatures and extract carbon from the water to grow their shells. Hog Island has made it simple and pleasurable for anyone to be a warrior for the ocean. Just belly up to one of their oyster bars and enjoy their “Sweetwaters” on the half-shell paired with Rosé for the Bay wine from Poseidon Vineyards—100% of the proceeds go to the San Francisco Baykeeper.

“Oysters reflect terroir more than any other food,” Finger says. “They are what they eat. Literally.”

Oyster Merroir

Forty-one years ago, John Finger and Michael Watchorn started Hog Island Oyster Co. with a $500 loan from Finger’s parents and a five-acre intertidal shellfish lease at the northern end of Marin County’s Tomales Bay. Finger knew a perfect oyster habitat when he saw it.

Tomales Bay is a fog-capped crooked crevice of an estuary. The jagged, boulder-dotted shores are bordered by Point Reyes National Seashore to the south and dairy cows grazing on green slopes on the north side of the bay. The pristine location includes wetlands and river tributaries, nutrient-rich waters, upwelling currents and intertidal activity that create a constant flux of saltwater and freshwater, making it prime bivalve habitat.

Hog Island set out to grow an oyster that was perfect for “slurping from the half-shell,” Finger says. To achieve this, they adopted the “rack and bag” method of oyster farming: seeding bags with baby oysters (known as spat) and placing them on the bed-frame racks in the intertidal zone. This setup is designed to help the spat feed better while being protected from predators. They also develop a deeper shell “cup”—thus enhancing slurpability.

The oyster that is native to this part of the California Coast, the Olympia, was being pushed towards extinction due to damage to the bays and overharvesting during the Gold Rush. Even when farmed, Olympias are small, slow growing and sensitive. Fortunately, three other types of oysters also thrive here: Atlantic, Kumamoto and Pacific. However, these can’t reproduce on their own, so oyster spat nurseries are necessary to the industry.

Finger’s current business partner, Terry Sawyer, joined the company in 1988. Both Finger and Sawyer come from science backgrounds. Finger studied marine biology at Southampton College on Long Island, NY; Sawyer left Florida to attend UC Santa Cruz. While pursuing his degree in marine biology and ecosystems, Sawyer began working at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, specializing in marine animal husbandry. The experience and expertise he gained there in creating healthy marine habitats were critically important at Hog Island; providing a steady supply of shellfish to market is not a simple or easy task. Seasonal rains flood into the bays, bringing runoff from agricultural lands, often halting harvests. To solve this problem, Sawyer devised an innovative series of wet-storage tanks used to hold oysters that are harvested before the rains, thus ensuring a steady supply.

It’s practice at Hog Island to place all their oysters after harvest into wet-storage tanks full of purified bay water before being sending them to market. In these tanks the oysters naturally cleanse themselves of any grit or undetected bacteria, thus providing an extra assurance of the health and quality of Hog Island oysters.

Oyster Bars

Today, throngs of oyster lovers head to the small town of Marshall to enjoy a meal at The Boat Oyster Bar, a full-service restaurant on the waterfront. It’s open Fridays through Mondays by reservation and on Thursdays for walk-ins. You can no longer buy oysters to shuck and grill there, but you can get them to go and shuck your heart out someplace else. You can also find their restaurants at Ox-bow Public Market in Napa, in the San Francisco Ferry Building and, more recently, at Marin Country Mart in Larkspur. The Mart restaurant opened in 2020—and shut down three weeks later due to Covid. To survive, they quickly pivoted to selling home meal kits and shipping oysters nationwide. When restrictions loosened, they set up a tent in the parking lot for people to gather and eat oysters outdoors. It remains popular to this day.

Climate Change Threats

The pandemic hasn’t been the only threat to Hog Island. A looming, potentially catastrophic one is ocean acidification, which is a symptom of climate change. Oceans are known to absorb about 30% of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. CO2 is naturally present in the atmosphere as part of the Earth’s carbon cycle, but human activities since the industrial revolution have altered that cycle, and continue to, both adding more CO2 to the atmosphere and obliterating natural carbon “sinks,” such as forests. Scientists learned that carbon is changing the chemistry of seawater, making it more acidic and less “calcium available” to sea creatures that grow shells. These protective coatings are becoming smaller, thinner and weaker.

“Ocean acidification threatens the success of many organisms with shells, such as mussels, clams and oysters,” says Tessa Hill, PhD, of the UC Davis Bodega Bay Marine Laboratory (BBML) and co-author of At Every Depth: Our Growing Knowledge of the Changing Oceans. “Those animals provide habitat for many other organisms, so there will be a cascade of impacts through estuaries and the ocean. Estuaries are susceptible to both ocean acidification and climate change, which means they may experience changes in temperature, pH and salinity in the future.”

Starting in 2005, oyster nurseries began having mysterious die-offs of their oyster larvae. Since then, scientists have determined that oysters are most susceptible in their earliest stages of life because the acidity makes it difficult for them to form shells. Hog Island has teamed up with Hill and other scientists at BBML to monitor the levels of acid and temperature changes in Tomales Bay.

In the meantime, shellfish growers are racing to save their oysters and keep their industry from collapsing. Scientific studies are finding that deeper water is more acidic, so if larvae can be grown in shallow, less acidic, water until they form a shell, they have a better chance of surviving. So Hog Island started its own hatchery in Humboldt Bay—the first in California. When that region’s logging industry faded out, commercial docks on the waterfront were left vacant, creating an ideal space to float rafts full of oyster spats in shallow water.

They innovated a custom floating upwelling system (or FLUP-SY) for young oysters leaving the safe confines of the nursery. These containers not only protect young oysters but also increase the upwelling of nutrients and phytoplankton in the ecosystem that oysters need to grow. This system increases the survival rate from 10% to 75%.

Secondary Harvests: Seaweed & Salt

Another way to help mitigate ocean acidification is by co-growing them with seaweed, as algae pulls carbon dioxide from the water to grow. Hog Island tried partnering with a seaweed company to mixed results, particularly from a permit standpoint. (The California Coastal Commission does not make innovation on the ocean easy.) But each year Hog Island’s oyster farming gear is festooned with the mineral-rich delicacy. The nori, sea lettuce and ogo used to be removed and composted, but seaweed is a super food that adds umami flavor and a hint of the sea that’s increasing in popularity around the world. So Hog Island applied to amend their shellfish lease from the state and in June 2022 were approved to sell the seaweed from May through October—the months when herring aren’t in the bay laying eggs on eel grass and seaweed.

In their recently opened a test kitchen in Petaluma, Hog Island is experimenting with new ways to incorporate seaweed into recipes and products. When satisfied, they introduce the results through their restaurants, using seaweed in everything from cocktails to condiments, seaweed salad and even savory seaweed granola.

“Most people eat dried seaweed snacks from Asia,” John says. “It’s hard to compete with that pricewise. But we are currently testing out the size of the market.” One of the products they’re selling is miso nori butter—which sounds like it would be delicious roasted on an oyster. The Petaluma location is not a restaurant, but it does have a fresh seafood market where you can pick up their famous oysters and other sustainable seafood and their products.

Another secondary harvest they’ve been developing for market is salt. “I spent a lot of time in France and I got fascinated with the rebirth of artisanal salt,” Finger explains. When transferring oysters into the onshore pens, they discharged saltwater from their tanks, but can’t just let the salt go into the ground. So Finger teamed up with Jeff Warrin, a local West Marin artist and salt enthusiast. They developed an evaporation method using solar and wood-fired heat to create a flakey finishing salt with the merroir (the marine version of the well-known concept of terroir, or local flavor) of Tomales Bay.

The Future

Hog Island is working with scientists and others in the industry to understand the genetics of oysters to find those that are resilient to climate change. And they’re developing a program for ranching purple sea urchins, which have overpopulated the Mendocino and Sonoma coast and devoured the bull kelp, which is important habitat and a super sequesterer of CO2. This ecosystem out of whack has hurt the red abalone population, and so Hog Island is looking at farming abalone as well. To achieve this, they’re not only collaborating with scientists, but also the Kashia band of Pomo natives in Ft. Bragg, Mendocino.

“The indigenous people have a working knowledge of animal husbandry and the changing ecosystems,” says Sawyer. “We are finding a synergy between their knowledge and scientists at Bodega Bay Marine Lab.”

Hog Island Oyster Co. is most likely innovating as you read this, so that the next generation can continue to grow, steward, collaborate and innovate in California bays and estuaries to bring us oysters. We can learn from Hog Island that sometimes the solution to pressing problems can be as simple as a perfectly cupped raw oyster shared with good company.