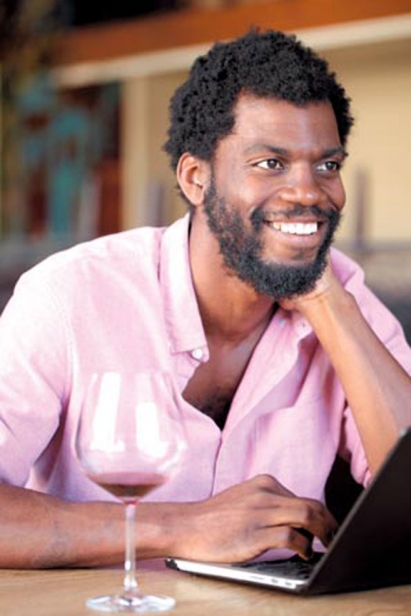

Stephen Satterfield, How Did I End Up Here?

I arrived in California in July 2010. It was an improbable move. Even if asked in April or May of that year, I would not have guessed I’d find myself in California in just a few months, or perhaps even in my entire life.

Well, maybe not my entire lifetime. I’d gotten a taste of California years earlier, as a 19-year-old college freshman from Georgia. My introduction was an impeccable house in Marin that was at once chic and rustic.

I remember a vivid green lawn studded with splashy flowers that looked fit to adorn the cover of a gardening lifestyle magazine. The yard had a happy scent, a pungent smell from embarrassingly plump Meyer lemons. I was already very much into food, so I knew what Meyer lemons were, but the fact that they were growing in someone’s backyard was astonishing. After all, I’d pretty much taken Meyer lemons to be the citrus world’s equivalent to truffle oil.

That same night I enjoyed a perfect sunset meal at Foreign Cinema. I was with one of my buddies from college and his parents were hosting us. That night, over a perfect San Francisco evening, lots of Sonoma County Pinot Noir and 20-year Tawny Port, the seeds of a future in California were planted in very fertile soil.

It’s funny recounting these details now. I’m pleased to say that in no way have I grown to take any of those citrus trees or lavish sunsets or fine meals for granted. My delight in these things has not diminished even one bit, though nothing will ever compare to the gaping awe of that first trip. The beauty of San Francisco plus the cool/casual/intellectual vibe was palpable, and felt just as I imagined it would. I’d been preparing to fall in love with San Francisco long before that first visit.

It started in high school, technically speaking, but really it started just from being birthed in the South. Growing up, my father was the chef of the family and our house was always the host for gatherings from mundane to grand and everything between. The torch was passed from my granny on my mom’s side. Her brick-walled kitchen in Decatur, Georgia, was once where we ate each Sunday after church. The kitchen was small, always warm and always permeated with aromas that implied many hours of kitchen labor.

Each Sunday, all our cousins, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, babies and grandbabies were summoned to the table. It was an easy summons to answer, because fried chicken, cornbread, mac and cheese and collard greens were most likely what was being served. Sometimes we’d have fried catfish and hushpuppies if my dad was in charge of the menu, but there were always lots of sweets. Madea loved her sweets and my entire family still does.

In 1989, my grandmother passed at only 59 years old. The sad and brutal truth of the matter is that my grandmother, who loved her sweets so, and who decorated my childhood with lovingly prepared cakes and cobblers, died of diabetes. Now, as I said, we can’t shake our sweet cravings, but it was a tremendous wake-up call for all of us.

As we grew older, dinners resumed at our house, but rather than the weekly gatherings I’d once known, ours were limited to holidays and celebrations. Luckily, our family is large enough that we were frequently hosting, and my father, Sam, is one of the best hosts you’ll ever meet. As I’ve grown older, I’m increasingly convinced that his ability to put people at ease while feeding them the best food he could was a very basic, but very profound lesson for me. I wasn’t really “into food” until later into my teens, but the reverence for food and the connection to food are rooted in some of my earliest memories in life.

I attended a rigorous private school in Atlanta. I was a poor student. That is to say, one of limited financial means and completely dire academic means. I found school—especially the ones I attended—to be a painstaking daily endeavor. I distinctly recall the persistent and engulfing voices that reminded me the world was much larger than that classroom, that school and that city. Those voices started early and grew up with me. So from that vantage, entering my junior year of high school, I’d finally switched to a more palatable school and started spending time with other angst-filled teens who shared my restlessness.

Burch and Lauren were two of my closest friends in those days. Not only did we provide solace for one another, we spent all of our free time—and even unsanctioned time—together. They both came from families that enjoyed good food. A surprising fact of my childhood—and one that is completely at odds with those dreamy Sunday suppers—was that many of my friends’ parents did not love food. Or they did, but the scope of their food choices was very limited.

I grew up in Atlanta in an era when food was rather nostalgic and unimaginative and worlds apart from its current burgeoning, experiential state. Burch and Lauren’s parents enjoyed food and their kids did too. And since their kids were my friends, I started to enjoy different foods. With these two, there were many food firsts: guacamole, Indian and, in a moment of total elation, my first soufflé. We watched Julia Child take two spoons back-to-back and rip into the puffy custard, howling as the steam poured out as if it were coming out of a chimney. We howled along with her. That was the first time I recall the thrill of making something.

I started to connect food to these transformational discoveries. This was also around the same time that I discovered wine, through Burch’s family. For someone who was eager to explore the world, food was looking like a good vehicle.

Mr. Shu wasn’t just Burch’s dad, he was my role model—a successful banking executive, with humility and culture that I’d rarely seen in Atlanta. A man this distinguished being so into wine was a strong reinforcement of all of the romanticism and refinement I’d already associated with wine. Hopefully there’s some statute of limitations on this, but let’s just say Mr. Shu had a European sensibility when it came to sharing wine with the “young ‘uns.”

I was quite lucky to avoid the typical slow ascent into fine wine. I started right at the top, from a cellar loaded with classic vintages from Chianti, Piemonte, Burgundy and Bordeaux. That was in my last year of high school and, though it took two years for it to manifest, I returned to those memories of fine wine and fine meals with the Shus.

Whenever I tell people my story, I am abruptly interrupted each time I utter the following:

“After high school, I moved to Eugene, Oregon for coll. . . “

“Wait—How’d you end up in Oregon?”

Randomly, it turns out. As part of that longing for life outside of the South, I decided that I would make my first adult decision, and the biggest one of my life up to that point, based on proximity (read: distance from) Atlanta. I don’t mean that in a scientific way either, I mean, I was just arbitrarily picking the farthest and most random places in the U.S. I could conjure on the map. I could’ve ended up anywhere, but Oregon was the first to give me the green light and even agreed to put Lauren and me in the same dorm.

After a very enjoyable (and recreational) first year of college, I made what turned out to be the real most important decision of my life: I left Eugene (and college) and moved just north to Portland, where I enrolled in Western Culinary Institute’s School of Hospitality and Restaurant Management. I’m not sure exactly what the genesis of that thought was, but I remember getting a very fast and urgent feeling that I needed to move to Portland and enroll in that program. I didn’t know anyone there, and had never thought seriously about attending culinary school before a couple of days prior to my decision to enroll.

On a Tuesday, I took a Greyhound bus to Portland. I had no money or credit, but was able to secure a rundown studio apartment adjacent to a methadone clinic and only two blocks from my school. The rent was a paltry $495 a month and matched the square footage dollar for dollar. That afternoon, I signed the papers and made my bus back down to Eugene. I had just enough time to pack and head back the next day to begin my new life, this time with a one-way ticket.

That’s really where it all started. It was so exciting at the time to be in a new city where I knew no one and vice versa. It was so thrilling, in fact, that I hardly even realized I was sleeping on a blow-up mattress on a hard floor that couldn’t last a night without me ending up on said floor in a deflated heap. I hardly realized that my kitchen was also my living room, my dining room, my bedroom and every other room in the house not called bathroom.

I didn’t catch on until far too late, but the only guy I’d befriended in the building (who was also a student in the school) ended up becoming addicted to heroin while we were there. Really strange times. But none of that stopped me from entertaining friends as they came along. This was definitely my father in me. I didn’t have anything, but I remember cooking some excellent meals and sharing them with excellent company in that tiny two-burner apartment.

During this period, I took a job at The Benson Hotel, which had a proper wine program. The sommelier there was Jeff Groh, and this was the first time I had seen a sommelier in action. He was young, talented and had a sharp wit and wardrobe. He definitely wasn’t doing anything to lessen my irrational ideas about the coolness of wine.

By the time I started taking wine classes as part of our culinary curriculum, I was already enrolled in sommelier classes via the International Sommelier Guild. Jeff began to allow me to host a daily tasting in the lobby of the hotel where I got to choose wines from obscure parts of the world and offer a complimentary tasting to “international guests,” that ended up perpetually filled with middle-aged ladies from Arizona and Washington.

For the first time in my life, I started studying. I studied wine every day and, rather than seeking approval from a teacher or institution, I judged my preparation based on how much value I could add to each of those interactions I had. Did I really know the region, the grape, the profile of the wine, the vintage? If I did, there was always a prompt in one of my daily tastings where I could put myself through the wringer.

By the time I actually turned 21, I felt like I’d arrived. Though my birthday night ended with some of the typical exploits of a 21st birthday celebration, the night began with Burch and me drinking 2002 Domaine Drouhin Pinot Noir and Barolo from 1999. I believe Produttori, but, honestly, now I can’t remember. What I do remember is the look on our server’s face when she found out how old I was. Yes, wine was cool.

The first decade of my career in food and wine has been an invigorating journey. My work has been filled with amazing people and adventures, including founding a nonprofit that helps black South Africans break into winemaking and managing some of the best restaurants in Portland, Atlanta and San Francisco. I’ve also been very proud to watch this city that laid much of my foundation in good food evolve from a humble, industrious, local food community into a city with restaurants so hip that even Brooklynites keep close tabs on them.

While my interests have broadened, my love of food and wine has not waned at all. My perfect evening looks exactly as it did 10 years ago: sharing a lovely meal and lots of laughter with friends over the course of a long evening.

It’s no surprise that a restless soul like mine wandered to new places, but what has been a surprise is how this love affair with food and wine has taken my attention, and quieted the pacing. In this love of food and wine, I have found my life’s purpose while establishing deep, lifelong connections. I’ve once again found the warmth of my granny’s kitchen, in a place that is a perpetual celebration of good food. When I stop to consider that, it’s very clear how I ended up in California.